How many words have been written and spoken this week about the burning of Notre Dame cathedral in Paris? Why would I add more? Because that's what I do, use words to find sanctuary. Why wouldn't I?

On July 24, 1872 in Concord, Mass., Ralph Waldo Emerson, a man of many words, wrote only two in his journal to chronicle the fire that had destroyed his family's home the previous day: "House burned."

I recalled this simple, yet infinitely complex journal entry while watching and reading about the Notre Dame cataclysm in "real time." So many words, so many reactions/opinions, including the default social media option: "No words."

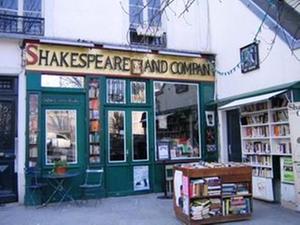

But there are always words. My first encounter with Notre Dame occurred about six years ago. I was walking along the Boulevard Saint-Michel in the general direction of Shakespeare and Company, a shrine for any word pilgrim. Turning the corner onto Quai Saint-Michel, I saw the cathedral. Perhaps inevitably, the photo I took was framed by signage outside a bookstore called Gibert Jeune.

But there are always words. My first encounter with Notre Dame occurred about six years ago. I was walking along the Boulevard Saint-Michel in the general direction of Shakespeare and Company, a shrine for any word pilgrim. Turning the corner onto Quai Saint-Michel, I saw the cathedral. Perhaps inevitably, the photo I took was framed by signage outside a bookstore called Gibert Jeune.

Words.

Heidi Carter, owner of Bogan Books in Fort Kent, Maine, observed in a compelling Facebook post: "Both the cathedral and the bookshop are very spiritual places with massive amounts of history soaked into all of the stones between them. Pilgrims have found their way to each landmark with vastly different goals in mind but similar outcomes. These travelers find a piece of themselves at these places that they might not have realized they had forgotten. For me, to imagine one of these landmarks without the other is very difficult."

Words have always been the lens through which I sort out my world. I sought perspective from Shakespeare and Company's Twitter feed. Not so long ago I'd stood in front of that bookshop, looking across the Seine at the cathedral.

Words have always been the lens through which I sort out my world. I sought perspective from Shakespeare and Company's Twitter feed. Not so long ago I'd stood in front of that bookshop, looking across the Seine at the cathedral.

April 15: "Thank you all for your concern and messages of support. The bookshop and our team are safe. We share in the heartbreak felt by everyone in Paris, France and around the world."

April 16: "In honour of Our Lady's resilience--and all the great literature she has inspired over the centuries--we have decided that tonight's reading with the brilliant @Damian_Barr will take place. Do come along if you're in the neighborhood.... Damian Barr and Adam Biles read from Victor Hugo's #NotreDame de Paris at the start of tonight's event."

Barr, whose new book is titled You Will Be Safe Here, tweeted: "I'm supposed to be going to Paris tomorrow to read from my novel @Shakespeare_Co . Maybe we could read lovely things about Notre Dame and the city instead? Some Bibliotherapy?... Heading to Paris now. Humbled to be there this evening. I hope to see some of you @Shakespeare_Co. We still need stories. Tonight's event will reflect that and the fire.... Last time I was @Shakespeare_Co the bells of Notre Dame marked the hours. Now it's well past midnight and I can hear gentle hymns from outside. Folk on the pavement with candles."

It has been pointed out often this week that when Hugo was writing Notre Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame), the cathedral was in a substantial disrepair and perhaps destined for ruin. His novel--his words--played a significant role in galvanizing public support for the eventual restoration. "There exists in this era, for thoughts written in stone, a privilege absolutely comparable to our current freedom of the press," he wrote. "It is the freedom of architecture."

Words.

In 2013, bundled for a mid-March snowstorm, I had walked along the slick sidewalks--often taking irresistible detours on narrow side streets--in the general direction of Shakespeare and Company, which promised sanctuary from the storm to a weary reader. Once inside, the near silence was almost as breathtaking as the cold wind had been. I browsed for a long time, exploring the ground floor stacks as well as the library upstairs. In the beautiful, iron-gated and densely stocked poetry section, I found some keepers, including W.G. Sebald's Across the Land and Water.

In the translator's introduction, Iain Galbraith writes: " 'Reading' in Sebald's poetry, however, is a process that not only responds to text. His poems read paintings, towns, buildings, landscapes, dreams and historical figures."

I carried my new treasures, stamped with Shakespeare and Company's iconic logo, outside again for a wet and chilly stroll across the Pont au Double, a bookish pilgrim's path, to Notre Dame.

In the Irish Times, Frank McNally recalled a first visit to Shakespeare and Company in the 1990s when he and his future wife "were invited upstairs for tea by the late proprietor, George Whitman. This was a common occurrence then. He used to host tea parties on Sunday afternoons for the various refugees who happened by, some of whom ended up staying, free of rent, while studying or writing. In that respect at least, the shop carried on the work of the medieval cathedral. In fact, among the signs Whitman had posted on the walls was one that read: 'Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise.' "