|

|

| photo: Greg Salvatori | |

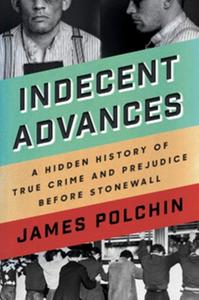

James Polchin is a writer, cultural historian and a Clinical Professor in Liberal Studies at New York University. He has held faculty appointments in the Princeton Writing Program, the Parsons School of Design, the New School, and the Creative Nonfiction Foundation. He has lived in London, Paris, and Florence, where he taught writing classes at NYU sites abroad. For more than 10 years he has been a contributing writer to the Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide. His essays and reviews have appeared in The New Inquiry, Lambda Literary, Brevity, Ducts magazine and the Smart Set. Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall (Counterpoint, June 4, 2019) is his first book.

On your nightstand now:

My reading stack is usually a mixture of essays, biographies and histories. Or, better, works that do all three. Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous by Christopher Bonanos, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel: Essays by Alexander Chee, When Brooklyn Was Queer by Hugh Ryan, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval by Saidiya Hartman and 16 Pills: Essays by Carley Moore.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Two Minute Mysteries by Donald Sobol. I had a few books in the series. Each mystery was only one or two pages long and featured the criminologist Dr. Haledjian. I remember being fascinated by that name. The mysteries included thefts, missing objects and even murders. Some tough stuff for a kid. Always the answer was printed upside down on the bottom of the page.

Your top five authors:

James Baldwin's precision and confrontation; Patricia Highsmith's double-edged sword in every plot; Edward P. Jones's lyrical force; Maggie Nelson's play with genre and a writer's presence; Rebecca Solnit's incisive intelligence; Edmund White's honesty and witnessing.

Book you've faked reading:

Moby-Dick. I tried, and will try again. But all that fishing.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Recently I've been talking about two books: The Meursault Investigation, a brilliant novel by the Algerian writer Kamel Daoud. He rewrites Camus's The Stranger from the perspective of the brother of the nameless man Meursault casually kills on the beach. And Édouard Louis's The End of Eddy, which tells the story of an assault Louis experienced one night when he brought home a man. He mixes fiction and memoir and sociological analysis as he searches to put into language the visceral and emotional impact of the violence.

Book you've bought for the cover:

The paperback version of Matthew Stadler's The Sex Offender, with its red filter over the Peter Hujar photograph, is as beautifully haunting as the book.

Book you hid from your parents:

I never had to hide books, thankfully. Growing up, we had a large bookcase of Book-of-the-Month Club selections, mostly from the 1960s. Once I stumbled on a queer passage in Midnight Cowboy by James Leo Herlihy, which led me on the hunt for other passages in other books. I'd do this reading in secret, huddle near the bookcase. If someone entered the room, I'd quickly replace the book. It was the first time that reading felt dangerous and powerful for me.

Book that changed your life:

James Baldwin's Giovanni's Room. The first book I read that had a complex queer center.

Favorite line from a book:

"I've come to understand," he writes, "that I am connected with other men's lives, men living in London with me. Or with other, dead Londoners. That's the story." --Neil Barlett's Who Was That Man: A Present for Oscar Wilde.

Bartlett's sense of history and biography is wonderfully enmeshed with the physical landscape, in ephemera, in details we might overlook. He makes us understand how the intangibility of queer history is not usually found in the official records but rather in between the lines of these records.

Five books you'll never part with:

Reinaldo Arenas's Before Night Falls: A Memoir reminds me how dangerous and politically powerful writing can be; Christopher Bram's Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America shows me how we can make the marginal a central story to tell; Rebecca Solnit's A Field Guide to Getting Lost feeds my love of longing; Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others has always challenged my ideas about seeing; Verlyn Klinkenborg's Several Short Sentences About Writing reminds me that writing is all about the simple sentence.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Truman Capote's In Cold Blood.