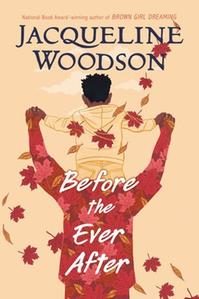

The best middle-grade novels centered on sports--among them books by Mike Lupica and Kwame Alexander, and now Jacqueline Woodson--are often not really about sports. In Before the Ever After, 12-year-old narrator ZJ doesn't even especially like sports. But he's crazy about his dad, the NFL dynamo Zachariah Johnson.

The best middle-grade novels centered on sports--among them books by Mike Lupica and Kwame Alexander, and now Jacqueline Woodson--are often not really about sports. In Before the Ever After, 12-year-old narrator ZJ doesn't even especially like sports. But he's crazy about his dad, the NFL dynamo Zachariah Johnson.

Before the Ever After begins in 1999, when Zachariah starts behaving like someone other than himself: his hands shake and he sometimes doesn't recognize people's faces. He gets monstrous headaches. For the first time in ZJ's life, he has a dad who's a yeller. ZJ lays all this out in free verse, a form that Woodson employed just as fruitfully in Brown Girl Dreaming: "Used to be I said my dad was home and people would/ come running to my house./ Now it feels like they're trying to run away." ZJ withholds how he feels from even his best friends--"I don't tell them that the quiet in our house/ is like a bruise. Silent./ Painful."

ZJ's mom takes Zachariah to various doctors for tests to try to get to the bottom of the mysterious headaches and memory lapses. (Woodson's author's note explains that in 1999 and 2000, when Before the Ever After is set, the medical community was still fuzzy on the link between brain injuries and tackle football.) Finally a doctor has an explanation; as ZJ interprets it, "All those times he got knocked down/ and knocked out, my daddy kept getting up/ but maybe some part of him/ stayed on the ground."

Before the Ever After may spur readers to mull over the risks of playing tackle football, but at heart the book is a love story. ZJ, a skinny kid who could practically swim in his dad's size 14 shoes, is as besotted with music as his dad is with football, and Zachariah has always accepted this about his son. He bought ZJ a guitar when the boy was seven--Zachariah had wanted to learn to play as a child but his parents couldn't afford lessons. Part of the heartbreak of Before the Ever After is the reader's gradual understanding of how far Zachariah came--to achieve professional greatness, to attain material wealth--only to find himself losing his ability to enjoy his success, not to mention parent his child. Woodson's text may be spare, but it has the emotional wallop of an offensive tackle. --Nell Beram, freelance writer and YA author

Shelf Talker: In this heartbreaking free-verse novel for middle schoolers, a 12-year-old describes his NFLer dad's decline due to head injuries sustained on the football field.