At a recent bookseller conference, you said you were finding essays easier to write during the pandemic than fiction. Could you expand a bit on that?

Part of it was size, and part of it was content. My fiction seemed frivolous. How could I say, "I'm going to make something up" with all this going on?

Do essays come to you in a flash, or do they evolve slowly? Or does it vary, depending on the subject?

Up until the pandemic--it might be true--I had never written an essay that hadn't been commissioned. It always came from an external place. My piece "Tavia" is different in the book from the essay that appeared in Real Simple. The editors said you can write anything you want, and I said I wanted to write a celebrity profile of my childhood best friend.

During the pandemic, I wrote long pieces completely for myself. I learned that from Liz Gilbert: every now and then write something just for yourself. When you're all finished, then you decide where to place it. I wrote "Three Fathers" because Kate [DiCamillo] had just lost her father and was going to write about it. I'd been wanting to write about my father for a long time, so we did it together.

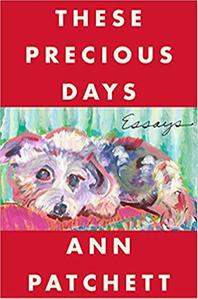

For the title essay ["These Precious Days"], I told Sooki I wanted to write about our time together, just for myself. I told her, "When I'm done, you can read it. It will belong to the two of us." It turned out to be 60 pages long. It wasn't a book, and it wasn't an essay. It was some massive thing in between.

For the title essay ["These Precious Days"], I told Sooki I wanted to write about our time together, just for myself. I told her, "When I'm done, you can read it. It will belong to the two of us." It turned out to be 60 pages long. It wasn't a book, and it wasn't an essay. It was some massive thing in between.

How do you decide the sequence of the essays?

I print everything out, put it in piles, then move them around. I suppose I could have just printed out the first page, but I printed out the whole essay. I'd see one and think "this doesn't fit," then I'd take it out. I hadn't written them to have those obvious connections, but why wouldn't they? I have one set of eyes, one set of ears. As I gave the book to different people, I asked them to say which is the weak sister. There were essays I wrote to fill the gap left by removing another essay.

Do you think becoming a bookseller has changed your writing in any way?

Becoming a bookseller changed me as a reader, and I'm sure it's changed me as a writer.

Now I only read galleys, five months ahead of pub date. I miss my old reading life. Parnassus has its 10th anniversary coming up. I am hounded by what I need to read. Yesterday, I read The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating, an old book [by Elisabeth Tova Bailey], published by Algonquin. It's a book of snail observations, and it's pandemically perfect. The author is sick, and her friend gives her a plant and a wild snail. By the end of the book, there are 118 snails. They're hermaphrodites.

Did you start your novel The Dutch House with the image of the house? With one particular character, Maeve? Danny?

It started with Maeve and Danny's mother. It started with the idea of not wanting to be rich. I grew up being raised by nuns; if you were a good person, you'd be poor. In every religion, holiness requires poverty. All the "stuff" impeded your spirituality. I thought of this after the 2016 election. These poor kids who grew up in this fabulous house.

These Precious Days predominantly explores mortality and the fragility of life. Yet each essay is infused with a pervading sense of humor and gratitude. How do you do that?

Michael, the oncologist [from "These Precious Days"], lives across the street from us. People always asked [about Sooki], "How's she doing?" Michael was incredibly helpful to me. I sent him the Harper's piece [where "These Precious Days" first published]. He asked me, "How can you do that? Be that open, that forthcoming?" I answered, "That's not how I write, that's who I am." In a novel, it's so much more about how I write. In an essay, it's who I am. If there are points weaving in and out, it's because I'm looking at the world through my eyes, noting them over and over.

Your essay "What the American Academy of Arts and Letters Taught Me About Death" perhaps best synthesizes the theme of this book: "The math in this room was inescapable--two hundred fifty seats at the table, and no one gets to stay."

I wrote that essay a year before the pandemic started. It didn't work. Maile [Meloy], a genius in all matters, figured it out. There was a lot more about John Updike--the kissing and not kissing commentary--and she said, "It seems like he's taking away from your happy moment. He comes across as creepy." He wasn't, but I took that part out. Now there's one sentence about Updike.

Originally, "These Precious Days" was the last essay. On a Friday night, I started it from a plural "we" present tense. I sent it to Patty, Sooki's best friend--and now my friend, too--and I said, "Read this and tell me if I can send it to Sooki." Patty read it aloud to Sooki without having read it first. Sooki died two hours later.

Do you believe in a larger unseen plan? If you hadn't picked up the galley for Tom Hanks's Uncommon Type and provided a quote, you would never have met Sooki, who was his assistant.

I don't believe in predestination. It has to apply to everything. I don't think you can take happy things and not bad things. There are moments when I show up and I'm brave and I trust my instincts. There are moments when I don't and I'm not brave and I don't trust.

Probably in so many of these galleys, I could make a connection and reap rewards. No one has time and energy all the time. With Sooki, I knew she was going to die; she didn't. I said, "Hey, I'll help. Come here." I knew I was up for it. That doesn't mean I'm always up for it. It's about the wonders and rewards of taking a chance. --Jennifer M. Brown, senior editor