I make the passage from study to kitchen, from computer to stove, a path taken so often that now I look for signs that the carpet is beginning to wear. Suddenly I remember, as I pass a bookcase and touch a book to even it up on the shelf with its companions, that there was a volume my bookseller companion urged me to look at if I am thinking of writing about an ordinary day in my life.

--Doris Grumbach, Life in a Day

|

|

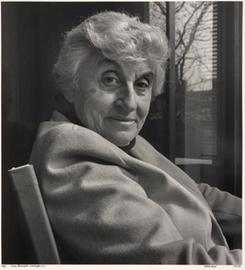

| Doris Grumbach (photo by Robert Giard ©Jonathan Silin) |

|

When I read last week that Grumbach had died, I was shocked, though not for the obvious reasons. She was 104 years old, so she'd had a good run. What saddened me was that she had somehow vanished from my reader's radar screen over the years. How do you forget an author whose work had at one time really meant something to you?

The question continued to haunt me after I'd written a brief Obituary Note for Shelf Awareness, so I did what readers do in such circumstances. I started rereading her, beginning with Fifty Days of Solitude and Life in a Day, followed now by Extra Innings. We have gradually become reacquainted.

![]() Fifty Days of Solitude was the first Grumbach book I ever encountered. Published in 1994, it found me during my second year as a bookseller. Maybe I read an ARC that intrigued, or was just drawn to the word solitude because I always rise to that particular title bait. In any case, I became one of her readers, catching up with previous works, like her first memoir Coming into the End Zone and a couple of the novels. By 1996, when Life in a Day was released, I was hooked.

Fifty Days of Solitude was the first Grumbach book I ever encountered. Published in 1994, it found me during my second year as a bookseller. Maybe I read an ARC that intrigued, or was just drawn to the word solitude because I always rise to that particular title bait. In any case, I became one of her readers, catching up with previous works, like her first memoir Coming into the End Zone and a couple of the novels. By 1996, when Life in a Day was released, I was hooked.

Then something curious happened; I forgot about Grumbach. That might be too extreme. If somebody had asked me on the bookstore sales floor whether we carried any of her books, I wouldn't have had to ask, "How do you spell that?" I knew. But nobody asked and I... just forgot.

As a frontline bookseller, I could have made the excuse that I was ever-drowning in the tidal flow of new books that sweeps away lots of fine writers. There are no doubt dozens of books I liked back then, yet no longer recall. Grumbach's voice was different, however. It connected with me, so all excuses seem inadequate.

On the other hand, rereading her now has been a gift, even if it's technically a regift. Since I'm in the age range she was when she wrote most of her memoirs, there is an added layer of empathy and engagement.

One aspect of the life on the page that has struck a chord this time is her at once ceremonial and personal engagement with the books surrounding her. She has a bookseller's tactile appreciation of the object as well as its contents that is not coincidental. Grumbach and her longtime partner, bookseller Sybil Pike, owned Wayward Books for decades, beginning in Washington, D.C., and continuing after they moved to Sargentville, Maine. Living in a house filled with books and with the shop close by ("So I made my way through high snow to the locked-up bookstore."), the quiet world Grumbach depicts is one where a book is almost always at hand.

![]() In Life in a Day, she gradually maps her reading stations, ranging from the kitchen ("I fetch the spoon, sit down again, stir, and open to page 41 of The Book of Common Prayer and begin to read aloud."); to "Base Camp 2½, the desk that faces the cove"; to the library ("Standing before these shelves is dangerous. I could spend the morning reinserting myself into one or another of these beloved books.") and even the bathroom ("I choose my reading matter for my time attending to eliminatory matters.").

In Life in a Day, she gradually maps her reading stations, ranging from the kitchen ("I fetch the spoon, sit down again, stir, and open to page 41 of The Book of Common Prayer and begin to read aloud."); to "Base Camp 2½, the desk that faces the cove"; to the library ("Standing before these shelves is dangerous. I could spend the morning reinserting myself into one or another of these beloved books.") and even the bathroom ("I choose my reading matter for my time attending to eliminatory matters.").

Grumbach is often distracted from her writing desk: "Oh well. In order to locate the book, I have to leave the computer before I have entered a single word of the work in progress, this sickly and unformed work. I find it necessary to go out of the study to find the book."

Once the book is located, "I sit on the couch in the library to scan its more than three hundred pages for the quotation I remember imperfectly. But I don't find what I'm looking for. I put the book aside. Once seduced, I know perfectly well I'll come back to it, so I leave it at another of my reading stations (beside the couch on which I sometimes nap)." We all know that feeling.

So I mourn the loss of Doris Grumbach. I'm sorry I forgot about her for a while, but I'm glad to be getting reacquainted with her words. Maybe she wouldn’t have understood my vanishing act; maybe she would:

As a partner in a store for used and out-of-print books for almost 20 years, I have seen the sad, endless flow of forgotten books sold to us for very little, and then consigned to our shelves or to the storeroom for a long stay. Some of these were once bestsellers for which no one has asked in many years, or books that were published with high hopes, sat for a few months at most on the shelves of a new bookstore, were returned to the publishers, remaindered, and then fell without a sound into the black pit of totally forgotten work. What other human effort, in the long run, comes to so little? Oh Lord, I think, and decide I will have lunch.