|

|

| Almost Corner Bookshop | |

Column ideas come to me from many directions and, as it turns out, destinations. On January 7, Italian bookseller Almost Corner Bookshop in Rome posted a link on Facebook to a Guardian article headlined " 'It altered my entire worldview': leading authors pick eight nonfiction books to change your mind."

Later that day, Dudley's Bookshop Café, Bend Ore., posted the same link, noting: " 'A noble spirit embiggens the smallest man.' If you'd like to embiggen your worldview, here's a list of 8 non-fiction titles that have opened the minds of their author readers. Props to those of you who also get the above reference...."

Always ready to have my worldview embiggened, I read the Guardian piece. Steven Pinker said his choice, Getting Better: Why Global Development Is Succeeding--and How We Can Improve the World Even More by Charles Kenny, "lifted my view of history and the current state of the world to a higher level."

Always ready to have my worldview embiggened, I read the Guardian piece. Steven Pinker said his choice, Getting Better: Why Global Development Is Succeeding--and How We Can Improve the World Even More by Charles Kenny, "lifted my view of history and the current state of the world to a higher level."

Mary Beard cited Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo by Mary Douglas as the work that "opened my eyes, and helped me see different things not just in Roman history but in the world around me too.... I am not sure that the answers I came up with were any more correct than those of Douglas herself. But her book showed me how to ask different questions--and it showed that a book doesn't have to be right to be important."

Margo Jefferson chose Ralph Ellison's essay collection Shadow and Act, noting, "Reading him, I realized that even great novelists (and poets) needed to write criticism, that criticism lets them delineate and transmit passion, character and history in ways that fiction did not. For me this change of hierarchies was a change of mind and a change of heart."

Jim Al-Khalili chose Consciousness Explained by Daniel Dennett, "a book that explained away one of the deepest mysteries of existence using logic and common sense. Whether right or wrong, it altered my entire worldview on the comprehensibility of reality."

Samanth Subramanian observed that soon after reading Surely You're Joking, Mr Feynman!, "my interest in a career in the sciences died. This was not Richard Feynman's fault. I was, at the time, immersed in a typical Indian high-school curriculum of physics, chemistry and mathematics: dense lessons that urged rote memorization or brute practice. Feynman made sure I remained interested in science long after I left any academic dreams behind."

How can anyone resist accepting the Guardian's challenge? What book made you see the world differently? For a time after reading the piece, I couldn't begin to narrow down the field. One book! And then, quite suddenly, I could...

How can anyone resist accepting the Guardian's challenge? What book made you see the world differently? For a time after reading the piece, I couldn't begin to narrow down the field. One book! And then, quite suddenly, I could...

In the mid-1970s, I was browsing the stacks at Tuttle Antiquarian Books in Rutland, Vt., which served then as a kind of retail bedrock for my reading life. In addition to an extensive used book inventory (the bookshop closed in 2006), the two buildings also housed the offices of Tuttle Publishing (which still exists as part of Periplus Publishing Group).

It's not an exaggeration to say that a significant part of my introduction as a reader to the world of translated books came from the new-title display shelves in Tuttle's old headquarters, where I purchased my first copies of titles like Zen Flesh Zen Bones by Paul Reps & Nyogen Senzaki; The Izu Dancer & Other Stories by Yasunari Kawabata; Spring Snow by Yukio Mishima; Seven Japanese Tales by Junichiro Tanizaki and so many others.

During the spring semester in 1970, one of the college courses I took was called "English Language." The professor was a diminutive, soft-spoken man whose passion for sharing the intricacies, history and infrastructure--especially semantics--of English was obvious, but sadly fell upon reluctant ears. It all seemed a little dry to me, especially compared with the English Lit courses I was taking at the time. So I dutifully showed up, took my B grade, and moved on. No lessons learned... yet.

Just a few years later, however, I found Zen Art for Meditation, and soon had a moment of sheepish, non-Zen awakening when I realized that the nice little man, the one I had all but dismissed, was Stewart Holmes, co-author of this wonderful, life-altering book. In effect, he became my teacher again, the one I'd been looking for but hadn't noticed when he was standing right in front of me. The first lesson was a well-earned dose of humility.

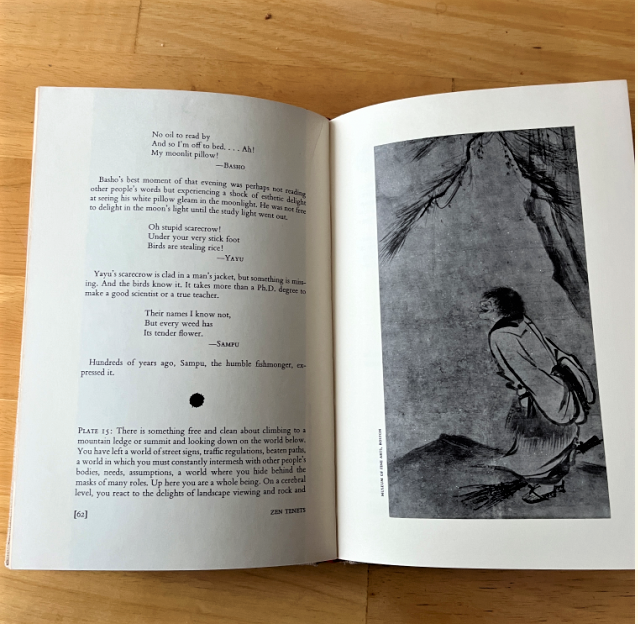

Their names I know not,

But every weed has

Its tender flower.

In Zen Art for Meditation, this haiku is introduced with the words: "Yayu's scarecrow is clad in a man's jacket, but something is missing. And the birds know it. It takes more than a Ph.d degree to make a good scientist or a true teacher.... Hundreds of years ago, Sampu, the humble fishmonger, expressed it."