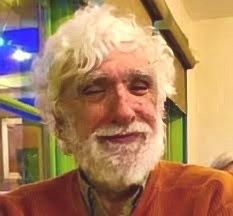

Don Barliant, co-owner of Barbara's Bookstores since 1967, died on December 9 at age 86. Over the years, Barbara's has been a model of bookselling innovation, at various points having stores and pop-up in train stations and airports in Boston, Mass., New York City, Philadelphia, Pa.; in Macy's stores; and in hospitals. Barbara's now has five stores in the Chicago area and five locations at O'Hare Airport. Here, Michael Boggs, co-founder of Carmichael's Bookstore, Louisville, Ky., remembers his 50-year friendship with Barliant that he calls "more like an epic journey, a Ben-Hur, a Lord of the Rings."

|

|

| Don Barliant | |

The first bookstore job that my not-yet-wife Carol and I had was at Barbara's in the early 1970s. Don and I had one brief talk before offering me, a humanities graduate who had read too much existentialism, a job as Barbara's bookkeeper. So I spent the next five years in the office of the slowly crumbling Wells Street store trying to wrestle debits and credits that were as arcane to me as Being and Nothingness. I also got to observe Janet buying new titles for the store, a black art that could only be accomplished with a Yoda-like belief you could use the Force to choose books your customers would want. It was one of Don's great traits that his enthusiasm and optimism made you believe you could succeed at anything.

Barbara's in the '70s and '80s was an incubator for a cadre of young booksellers who would go on to move up through the ranks of publishing, advancing the culture from its staid, gentleman's hobby into a business with a future. Clerks became sales reps, sales reps became sales managers, and some even moved into editorial and ran their own imprints. My wife and I benefited greatly from this crash course in bookselling, and in 1978 we started Carmichael's Bookstore in Louisville. This was only possible due to the generous mentorship of Don and Janet, who never failed to maintain an exceptional openness about how an independent bookstore should be run in order to survive. Janet even saved us from becoming a Book Nook or Bookshelf or My Back Pages by giving us the Carmichael's name, a combination of our names.

One of Don's most appealing skills was that he was a terrific storyteller--and I, as a half-Cuban, half-Southerner, had some yarn-spinning chops of my own. Over pizzas in Chicago, on beaches in the Caribbean, in manor house hotels in England, we swapped stories ranging from follies of youth to the madness of a bookseller's life. We both knew how to polish the dull parts, stretch the highlights even higher, and groused when our spouses interjected with "facts." I'm not sure he was a good storyteller because he was a good bookman or vice versa.

Finally, Don was a people person. An omnivore of curiosity about people, he would talk to anyone from physicists to financial wizards, from cashiers to chefs. He asked about their jobs and listened to their dreams for the future. He had a unique mix of empathy and street smarts to nudge them along to bigger and better lives.

Spending time with Don was always an adventure for me. Early on a quiet morning before he died, I spent some time talking to him. I said that I respected some people, I admired some people, but now, in my 75th year, he was the only person I still looked up to. In its most traditional sense, Don lived the life of a man in full.