|

|

| Dave Eggers (photo: Brecht Van Maele) |

|

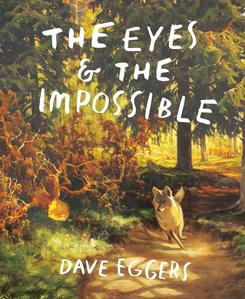

On Monday, as part of the American Library Association's 2024 Youth Media Awards, Dave Eggers won the John Newbery Medal for the most outstanding contribution to children's literature with his middle-grade novel, The Eyes and the Impossible, illustrated by Shawn Harris. In this title, simultaneously published by Knopf Books for Young Readers and McSweeney's Publishing, Johannes the dog introduces readers to his life in a bustling and vibrant urban park.

The Eyes and the Impossible is an unusual book for a few reasons. The first being its publication: it was released simultaneously by two publishers. Would you tell our readers about that choice and the differences between the two editions?

It's an arrangement Knopf has been kind enough to let us do many times in the past, usually with my books for adults. Often, we have an idea for a special edition, and Knopf has been generous in letting us put out a simultaneous version. In this case, early on I had an idea for a bamboo-covered book and, about four years ago, we started asking our printer if they could do it, making prototypes, refining them, trying again.... As a kid I always reveled in the craft of books, and sought out unusual editions, so our wooden edition is for those readers who like a weird and sumptuous version, something that exists a bit outside of time.

A second unusual aspect is the illustrative style: the illustrations are "classical landscapes by artists long departed" with images of Johannes the dog painted in by Shawn Harris. This is your third book with Shawn Harris, correct?

A second unusual aspect is the illustrative style: the illustrations are "classical landscapes by artists long departed" with images of Johannes the dog painted in by Shawn Harris. This is your third book with Shawn Harris, correct?

I think so. We started with Her Right Foot, and then did What Can a Citizen Do? And then, back around 2018, Shawn and I met at Book Passage in San Francisco, and that's where I asked him to help create this crazy wooden edition and the art inside. I'd written a draft of the book, and started showing Shawn pages, and I had this idea that about every 20 pages, there would be a two-page spread of sumptuous landscape art. At that point Shawn and I didn't know if he would paint the landscapes from scratch, but at some juncture we cooked up the idea of painting Johannes into existing, Old Master landscapes. That had a nice overlap with one of the book's themes, which is Johannes's new awareness of, and obsession with, visual art. To have Johannes painted into these classic landscapes seemed a perfect solution. Once that was the concept, Shawn took it from there. He's the most versatile artist I know, and at this point we have a shorthand. He takes the germ of an idea and realizes it almost effortlessly, and far beyond my expectations or hopes.

And a third (perhaps) unusual thing about the book is the focus. The book begins with a note: "This is a work of fiction. No places are real places. No animals are real animals. And, most crucially, no animals symbolize people." Why did you want to write dogs that "are dogs," birds that "are birds," goats that "are goats," etc.?

I love Orwell's Animal Farm, and I've written political books myself, so I didn't want to anyone to read Eyes thinking it was a political allegory. I really wanted readers to allow the story to be itself--not a means to comment on contemporary American or world politics.

How did you get into a place where you could write Johannes the dog?

I interviewed a number of dogs, and that was so helpful. They were very forthcoming. Later, when I had a draft, I read them sections of it (because most of them cannot read). Their notes were very astute, which is what I expected.

What was it like creating Johannes's physical world? Did you have a map in your head?

Some of the setting is based on elements of Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, a park I've more or less memorized in my mind. San Francisco locals will recognize places and features, but at a certain point the book departs from that park's geography. There's something nice about setting a book in a place you know well but giving yourself the freedom to invent or deviate from it. You need the grounding of the real setting you know, but also the freedom to break out of it.

Have you been surprised by the response to this book at all?

The book is so personal and eccentric that I wasn't sure who would connect with it. In some ways I thought it might be too weird for a lot of readers. The prose is so loose and loopy in places, Johannes's thinking so nonlinear, that I really didn't know what anyone would make of it. And then there's the fact that Johannes sees the sun as God and clouds as her messengers; his worldview is highly unusual. But when early readers responded to it, I was happily surprised. This recognition from librarians all over the country, though, is just astounding; it means the world to me.

Is there anything else you'd like to add or share with Shelf Awareness readers?

Support your local independent bookstore! From day one, the indies supported this weird little book and pushed it out into the world. Without the handselling of indie booksellers, I don't know where we'd be. --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness