|

|

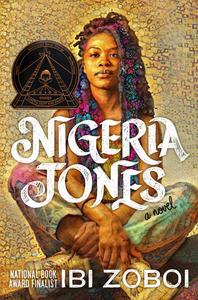

| Ibn Zoboi (photo: Nicole Mondestin) |

|

Earlier this week, the American Library Association announced the 2024 Youth Media Award winners. Author Ibi Zoboi won the Coretta Scott King (Author) Book Award, which recognizes "an African American author and illustrator of outstanding books for children and young adults," for her young adult book Nigeria Jones (Balzer + Bray).

You have been awarded a CSK every year for the past three years: an author honor for The People Remember Us, illustrated by Loveis Wise, in 2022; an author honor for Star Child in 2023; and now the author award for Nigeria Jones in 2024. How are you feeling about getting the win?

I am immensely proud of this recognition. There are so many ways to define success for every book, especially when I'm writing about topics that most readers are unfamiliar with--Kwanzaa, science-fiction author Octavia Butler, and the daughter of a Black separatist group leader. I'm intentional about bringing ideas and stories that I don't often see in the media. So it's always a win to just have those books out in the world. It's important that I remain humble so that I meet every recognition with deep gratitude.

Would you tell our readers about the book? What inspired it?

Nigeria Jones is the homeschooled daughter of a Black separatist leader in Philadelphia. When her mother disappears, she's left to care for her baby brother and take on the duties of helping her father care for their community. But a family friend shares a letter her mother had written to a prestigious private school. She learns that her mother had her own dreams for her, and Nigeria sets out on a journey to forge her path, liberate herself from her father's control, and peel away at the layers of her mother's absence all while making new friends and exploring romantic relationships with two very different boys.

I've seen this book referred to as "the Constitution of Nigeria Jones." Why did you decide to format this book with a preamble, articles, amendments, etc.?

I've seen this book referred to as "the Constitution of Nigeria Jones." Why did you decide to format this book with a preamble, articles, amendments, etc.?

I officially became a U.S. citizen when I was 19, at the same time that I was learning about the real history of this country in terms of slavery and the Civil Rights Movement. As part of the naturalizing process, we had to be familiar with the U.S. Constitution. It was the first time I remember thinking about whether the Constitution really applied to me as a Black immigrant girl. I've always wanted to write a book that tackles Black girlhood and the Constitution, and using the framework could help readers to really think about what those articles and amendments mean in our daily lives. I wanted to ask in big and small ways, "Who was written into the Constitution and who was left out?"

Could you speak to the quotes that open each chapter?

Those quotes are either from or about important figures in American history, including Haiti's founding fathers. All of them are about freedom and liberty. My character had to learn about all these important people as part of her homeschooling, but when she begins to question her place in her family and in the world, she remixes them to fit her own ideas of freedom.

This book focuses on Black women, Black mothers, Black girls. What would you like readers to take away from this book? Who do you hope reads this?

I hope everyone reads this book because my character is gripping with layers upon layers of marginalization. Acknowledging intersectional identity allows for greater empathy. Marginalized young people are grappling with how to define different parts of themselves and show up authentically in the world.

Black girls, Black mothers, and Black women have a unique set of circumstances they have to navigate in order to feel validated, supported, and seen. I remember seeing a post on social media where someone said, "Police brutality is to Black boys and men what the maternal health crisis is to Black girls and women." This is absolutely true. But there are a plethora of books, movies, and news stories highlighting police brutality and not about the alarming rates of maternal mortality. This is a national crisis in the same way that police brutality is a national crisis, and it goes back to the Constitution. Who gets to live freely? Whose rights are protected?

Places--Philadelphia, the Village House--are very important. What purposes do these specific settings serve?

Since I wanted to infuse the Constitution into the novel, Philadelphia was a no-brainer. This book also pays homage to Black separatist communities, namely the MOVE organization, which was founded in Philadelphia. The city and the state of Pennsylvania were founded by William Penn, who was a Quaker. The Quakers were considered separatists at the time and had some radical ideas about society and were the first abolitionists. The Village House is a communal living space where the members of the Movement can put their altruistic ideas into practice, much like the Amish, Quakers, and other separatist communities. But who gets to be sovereign in this country? Who is protected under the Constitution when members of our society decide to opt out, like the Movement, or opt in, like Nigeria Jones?

Why did you want to make Black-centered education key to Nigeria's story?

Afrocentric schools or Freedom Schools have always been an integral part of this country. There's a fairly recent New York Times article about the schools that continue to thrive, especially now when school districts are rife with discrimination. Philadelphia has a number of both Quaker schools and Freedom Schools, and I wanted to juxtapose those two educational philosophies and place a girl in the center to ask, "Which environment will affirm her identity? What sort of school environment will allow a highly intelligent, headstrong Black girl to thrive?"

Was there anything you wanted to include but couldn't?

Early drafts of Nigeria Jones included essays written by my character. I wanted readers to know about the Black and Indigenous girls in American history who were connected to either the founding fathers or the founding of this country. Ona Judge was 16 years old when she ran away from the capital of the country--she was enslaved by George Washington, who pursued her for years. There was Sally Hemings, who was also a teen when she was held captive by Thomas Jefferson. Sacagawea was in her late teens when she led Lewis and Clark across the Pacific Northwest. There were short essays about Mary McLeod Bethune and Susan B. Anthony and the ideas surrounding body autonomy. But at that point, it would've been an entirely other book. My editor was absolutely right in helping me to make sure that readers stay with Nigeria's story.

Is there anything you'd like to add?

I haven't always been confident that readers will want to tackle such a heavy, cerebral book. But I've been to school visits where I had to present Nigeria Jones, and I'm absolutely blown away by the readers who are craving this sort of intellectual rigor and want to step into the lives of teens who don't look like them. In Philadelphia, I signed several copies that were dog-eared and written in the margins. A couple of weeks ago, a boy told me how much he related to Nigeria's story because his father didn't want him to leave China to go to school in America. I'm glad this book is out in the world, and I'm confident that it will reach the readers who need it most. --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness