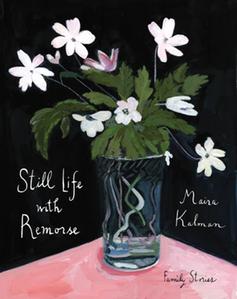

In the 39 entries and abundant (more than 50) illustrations of Still Life with Remorse, Maira Kalman explores the many varieties of remorse, with humor and poignancy.

In the 39 entries and abundant (more than 50) illustrations of Still Life with Remorse, Maira Kalman explores the many varieties of remorse, with humor and poignancy.

Fans of her previous works, such as Principles of Uncertainty and Women Holding Things, will recognize Kalman's charming, insightful, sometimes wistful meanderings about subjects as varied as her parents, Leo Tolstoy, and Clara Schumann. Her paintings include several of Tolstoy; Brahms and Chekhov on their death beds; Sarah Bernhardt "in bananas chapeau"; and the French poet Mallarmé, who "outdid all the rest in the looks department," and whose gray eyes seem to stare out from the pages. Her recollections of family, meanwhile, get "still life" treatments, in the loose lines of a Matisse, with telling objects such as the bouquet of flowers Kalman's father kept fresh at her mother's hospital bedside, and the "heavy black coat" that saved the life of a relative who "got involved with unsavory people/ Or he did something unethical./ It is unclear."

Such phrases as "It is unclear" or "Accounts differ" punctuate the entries. Kalman's pieces allow readers room to bring their own experiences into the details of a kitchen-table scene between two estranged, aging sisters-in-law, for instance, in "The Place Was a Mess"; or to reflect on the personal cost of the Holocaust. Kalman's father and two brothers left Belarus and their parents (who stayed with their dry goods store) for Palestine in 1939; their parents were murdered by Nazis. She balances these weighty moments with witty, often gallows humor. For instance, Kalman describes the frightening story of her sister Kika, born in 1945 with pneumonia (Kika survives), and moves into a tale of penicillin, Françoise Gilot, Picasso, and Dora Maar. She pairs the entry with a stunning still life of a bowl of cherries (with which Picasso wooed Gilot) on a square red table covered with a scalloped white cloth. The wry coupling typifies the dark comedy underlying the volume.

Kalman's pièce de résistance may be "What Could Possibly Go Wrong?": "The Romanovs could have lived longer if they/ had just been a teeny bit nicer to their people.// But they had not an iota of remorse/ about anything.// Lenin and Stalin?/ Same same./ Not an iota of remorse.// This is lack of remorse on an epic scale." Family situations incur the greatest instances of remorse, but friendships are not immune. Kalman's mother takes a proactive stand in "Chicken Fat": "She worried that if you made a friend you/ were bound to be disappointed and then what?/ How do you get out of it?/ Better not to make friends and not be disappointed."

Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, and yet Kalman assures readers that as long as there's music and art and flowers and laughter, there are moments of "merriment/ And good cheer," too. --Jennifer M. Brown, reviewer

Shelf Talker: Maira Kalman perceptively examines--with meaty anecdotes and abundant illustrations--the many forms of remorse as well as its antidote.