|

|

| photo: Leah Mahan | |

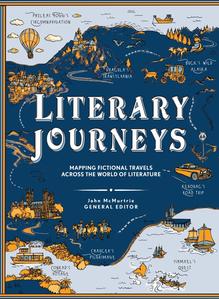

John McMurtrie served as the books editor of the San Francisco Chronicle for a decade and was an independent book editor, senior editor at Zyzzyva, an editor for McSweeney's, and a contributing editor of the quarterly literary travel magazine Stranger’s Guide. He's currently nonfiction editor at Kirkus. McMurtrie is the general editor of Literary Journeys: Mapping Fictional Travels across the World of Literature (Princeton University Press, September 10, 2024), a beautifully illustrated guide to important journeys in world literature, with contributions from Robert McCrum, Susan Shillinglaw, Maya Jaggi, Robert Holden, Suzanne Conklin Akbari, Alan Taylor, Michael Bourne, Sarah Mesle, and dozens more.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

One resplendent book can take you around the world through a look at more than 75 works of fiction. The book? It's called Literary Journeys.

On your nightstand now:

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas (reading it to my teenage daughter; it's more than 1,200 pages long, so we should be done by 2034); Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton (passed on to me by said daughter, who no doubt hopes to get it back by 2034); Every Man for Himself and God Against All by Werner Herzog (which I will attempt not to read aloud in a breathy, Herzogian voice); A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles (started reading it to my teenage son, who's now finishing it on his own, the little thief); Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York by Ted Steinberg (geeking out on urban esoterica, including ideal dinner party conversation topics such as colonial-era waste disposal); and Mudlark: In Search of London's Past Along the River Thames by Lara Maiklem (making me want to buy boots and a plane ticket to England).

Favorite book when you were a child:

The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis. In my childhood brain, little had as much magical allure as the wardrobe through which four young siblings travel in these stories. And I can still conjure the taste of my own version of Turkish Delight; I didn't know that the stuff actually existed until years later, and its flavor was far more disappointing than what my mind had imagined.

Your top five authors:

James Baldwin (a fierce intellect guided by compassion), Julian Barnes (a humanist with a wry worldview), Tony Horwitz (a questing observer who brought the past to life with great humor), Vladimir Nabokov (a supremely nimble wit), Lauren Redniss (a singular talent, equally gifted as a writer and artist).

Book you've faked reading:

Any Harry Potter book. Easier than admitting the truth and having fellow parents at bygone kiddie parties look at me aghast, shocked that I was not a member of the J.K. Rowling cognoscenti.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

The Black Russian by Vladimir Alexandrov. An underappreciated biography of Frederick Bruce Thomas, a son of former Mississippi slaves who, after many travels, strikes it rich in Moscow as a nightclub impresario, renaming himself Fyodor Fyodorovich Tomas. A stirring and ultimately tragic story that lays bare the pernicious reach of institutional racism.

Book you've bought for the cover:

Japan: The Cookbook by Nancy Singleton Hachisu. A handsome Phaidon title that's bound in what's made to look like bamboo.

Book you hid from your parents:

Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller. I enjoyed the novel enough that I could hide it only so long, eventually reading it out in the open. Upon seeing the book, my father registered his mild disapproval, which saddened me. I doubt he had read the novel, but I'm sure the fact that it been banned in the U.S. until 1964--having been deemed "obscene"--swayed his opinion. Such is the malevolent power of book bans.

Book that changed your life:

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller. Along with Kurt Vonnegut's novels, Heller's masterpiece awakened my teenage mind to looking at life through an absurdist lens. So many hilarious scenes--as well as Snowden's harrowing death--are fresh in my mind, more than 40 years after I devoured the novel. I still own the copy that I read at my grandparents' crumbling house in Normandy over the course of a summer. When I think of the novel, I hear the doleful ring of their town's church bells.

Favorite line from a book:

Three simple words in Anthony Doerr's rightfully acclaimed novel All the Light We Cannot See: "Es-tu là?"--"Are you there?" The words are spoken by Werner when he and Marie-Laure hear each other, at last, in person. He is a German soldier, and she is a French girl, and they have formed a bond that exists beyond their nationalities. Books very rarely make me cry, but this line got me when I read it 10 years ago.

Five books you'll never part with:

Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child, Louisette Bertholle, and Simone Beck (my late mother's 1963 edition); The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley by Malcolm X (my 1983 high school copy); Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell (my late father's 1961 paperback); Le Petit Larousse encyclopedic dictionary (a pre-Internet, dinner table bible of my youth); The New Biographical Dictionary of Film by David Thomson (a smart, opinionated, and indispensable door stopper for any film lover).

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov. Will this Soviet satire be as sly and wondrous as I recall it from 35 years ago (when the Soviet Union existed)?

Book you're afraid to read again for fear that it'd be a letdown:

Dune by Frank Herbert. As a child, I was taken in by the sandworms and magical spice and political intrigue--the earnest gloom and doom of it all. Perhaps best left undisturbed, frozen as a memory from long ago.