|

| photo: Idil Sukan |

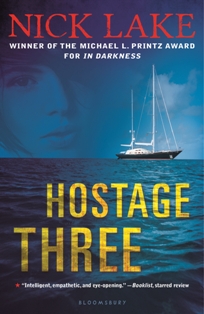

Nick Lake won the Michael L. Printz Award for his 2012 YA novel In Darkness, the story of a 15-year-old waiting for rescue in a collapsed hospital in Haiti after a devastating earthquake. The book weaves together the teen's present with the country's past--including Toussaint L'Ouverture and his fight for independence. Lake's new book is Hostage Three (Bloomsbury, November 12, 2013) , in which Somali pirates take 17-year-old narrator Amy, her wealthy banker father and his new wife hostage. Lake lives in Oxfordshire.

On your nightstand now:

I keep books on my nightstand but also in my shoulder bag: hardcovers for the nightstand, usually, and paperbacks for the bag, which I carry to work. I also have an e-book reader, but only use it for submissions (my day job is as an editor). I'm not sure why that is.

My current hardcover is James Salter's All That Is. He's a fascinating writer, even if I'm not sure that I precisely enjoy his books. There are authors--like Alice Munro and Marilynne Robinson--who write prose that is beautiful in its rhythm and inflection that flows like music. Salter generally writes more matter-of-factly and in short, simple sentences. But he also has a remarkable ability to depth-charge his books with startling lines that act like little detonations, compact and surprising as poetry. Such as when the protagonist of A Sport and a Pastime notices someone in rural France who has "the face of a girl who might move to the city."

With All That Is, he's apparently tried to move away from that. He has said that he wanted to write a book "where nobody underlines anything," presumably because he feels that pulling out these individual lines, as people tend to do with his books, frays the fabric of the whole, or misrepresents it. But he can't resist one or two. I have been mulling for days now over this astonishing sentence, describing the aftermath of a battle in the Pacific theatre of World War II: "...swollen bodies lolling in the surf, the nation's sons, some of them beautiful."

Why is that final coda--"some of them beautiful"--so arresting? I think because it's an abrupt transition on several levels. In terms of narrative perspective, it takes you from general narration to--presumably--the opinion of the character through whose eyes you are seeing the scene. But also it's a sudden shift from abstract cliché--"the nation's sons"--to specificity. At the same time, I suspect it's deliberately puncturing another cliché, the idea of beautiful young men senselessly killed by war. Here, only some of them are beautiful. It's a reminder that death is not going to magically render every corpse aesthetically pleasing. And all of this in four words.

That said, and as much as I admire the writing and the aim to record the real, with all the shapelessness and banality that goes with it, I am fundamentally a philistine who likes storytelling. So the paperback I'm currently reading is the latest Fred Vargas. I love crime and I've been on a French kick since reading Alex by Pierre Lemaitre. A few fellow editors recommended it to me, and I can see why: it's a book likely to be especially appreciated by those who have read and worked on a lot of stories because it's so original and clever in its structure. I won't say much about it because this answer is far too long already, but it pulls off at least one twist that I haven't seen before.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Favorite book when you were a child:

Roald Dahl's The Giraffe and the Pelly and Me. We had it on tape and would listen to it on car journeys. There's still a part of me that believes one day a pelican will come along and carry me off on adventures in its beak.

Your top five authors:

Five is really hard. But okay: Marilynne Robinson, Stephen King, Haruki Murakami, Margaret Atwood, Jonathan Franzen. Ask me again another time and it would probably be different.

Book you've faked reading:

All of Thomas Hardy. I studied English language and literature at university and was generally very good about reading the required texts. But I just couldn't get into Hardy. It was like swimming in cement. I read the York notes and pulled a sickie for one of my tutorials, I think.

Book you're an evangelist for:

John Crowley's Little, Big. It deserves to be in the canon of great literature but carries a fantasy stigma. It's just a great, beautiful, sprawling world of a book, full of characters you fall in love with, and dealing with enormous ideas about myth and magic and memory and the wonder of all the things we take for granted--the wonder of being a human with a thinking, conscious mind and an unconscious capacity for story. It's a fairy story that gradually reveals that we are the fairies. We are magic, because our imaginations have invented magical things.

If it's not cheating I'd also throw in The Sterkarm Handshake by Susan Price. It did win various prizes when it was published so it's hardly unknown, but I don't see it mentioned much now. It's such a stunning YA novel, though--beautifully written, intelligent and incredibly moving.

Book you've bought for the cover:

I think I maybe bought How I Live Now by Meg Rosoff for the cover--that is, the U.K. cover with the foiled butterflies. It was so beautiful and unusual, at the time. I'm glad I did, too, because I think it's one of those rare, perfect books.

Book that changed your life:

It's not a book, per se, but I'd go for Shakespeare's The Tempest. I vividly remember seeing it when I was 17, and thinking, "This is the most beautiful thing that has ever been written." That was a very teenage thing to think, but I still think it's true. Shakespeare poured a whole lifetime of talent and experience and heartache into that play. The visceral power of it, as a testament to human imagination, is just breathtaking.

Favorite line from a book:

That changes all the time, too, but at the moment it might be "and the walls became the world all around," from Where the Wild Things Are. Every economical line of that book is pure poetry.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

There are so many: Middlemarch, Coraline, Gatsby. All those books that had a huge impact on me, and which it would be lovely to experience again for the first time. But most of all would probably be Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy. I have a daughter named Lyra, after all. Most people who read a lot do it for different reasons at different times: to admire great technical skill; to learn; for entertainment; to experience a different perspective; or simply for escapism. But occasionally a book manages to utterly transport you to another world, while giving you characters you will love forever, and expanding your perspective with surprising ideas. Pullman did that, for me. The intellectual ambition married to the sheer storytelling joy is something quite special.

Amazon has raised its minimum order for "Free Super Saver Shipping" from $25 to $35, saying to customers that "this is the first time in more than a decade that Amazon has altered the minimum order for free shipping in the U.S."

Amazon has raised its minimum order for "Free Super Saver Shipping" from $25 to $35, saying to customers that "this is the first time in more than a decade that Amazon has altered the minimum order for free shipping in the U.S."

"Thanks to the support of longtime customers,"

"Thanks to the support of longtime customers,"

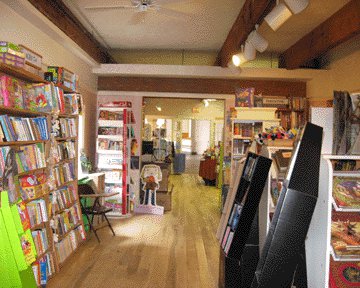

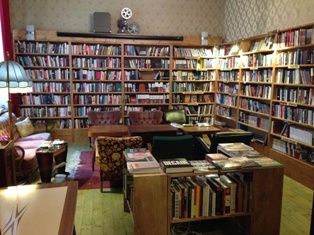

After graduating from university, Roman Kratochvila, a native of the Czech Republic, worked for a year at the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris, France. He had never worked as a bookseller before; a friend who worked at the store was leaving and set Kratochvila up with the job. After that, there was no looking back. "I loved it," said Kratochvila. "I decided [bookselling] was what I wanted to do."

After graduating from university, Roman Kratochvila, a native of the Czech Republic, worked for a year at the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris, France. He had never worked as a bookseller before; a friend who worked at the store was leaving and set Kratochvila up with the job. After that, there was no looking back. "I loved it," said Kratochvila. "I decided [bookselling] was what I wanted to do."

Although the cafe has proven to be a good draw, Kratochvila described it as a "work in progress." Bagels were added to the menu recently, and he plans to continue expanding the food offerings.

Although the cafe has proven to be a good draw, Kratochvila described it as a "work in progress." Bagels were added to the menu recently, and he plans to continue expanding the food offerings.  Two years after being acquired by Amazon, the

Two years after being acquired by Amazon, the  Bookseller

Bookseller

Melville, who spends his days at

Melville, who spends his days at  Melt: The Art of Macaroni and Cheese

Melt: The Art of Macaroni and Cheese In the next few months, when

In the next few months, when  "I wanted each theme to evoke or represent a slightly different kind of feeling, a slightly different kind of joy or insecurity or whatever," explained Sampsell. "I've always loved writing about relationships and about people, and writing these turned into a really exciting and fun thing to do."

"I wanted each theme to evoke or represent a slightly different kind of feeling, a slightly different kind of joy or insecurity or whatever," explained Sampsell. "I've always loved writing about relationships and about people, and writing these turned into a really exciting and fun thing to do."

Favorite book when you were a child:

Favorite book when you were a child: In Matt de la Peña's (Mexican WhiteBoy) compulsively readable thriller, a new disease attacks and runs rampant through the poor population in the U.S. on the border of Mexico, and a tsunami threatens the lives of passengers and crew on a luxury liner.

In Matt de la Peña's (Mexican WhiteBoy) compulsively readable thriller, a new disease attacks and runs rampant through the poor population in the U.S. on the border of Mexico, and a tsunami threatens the lives of passengers and crew on a luxury liner.