|

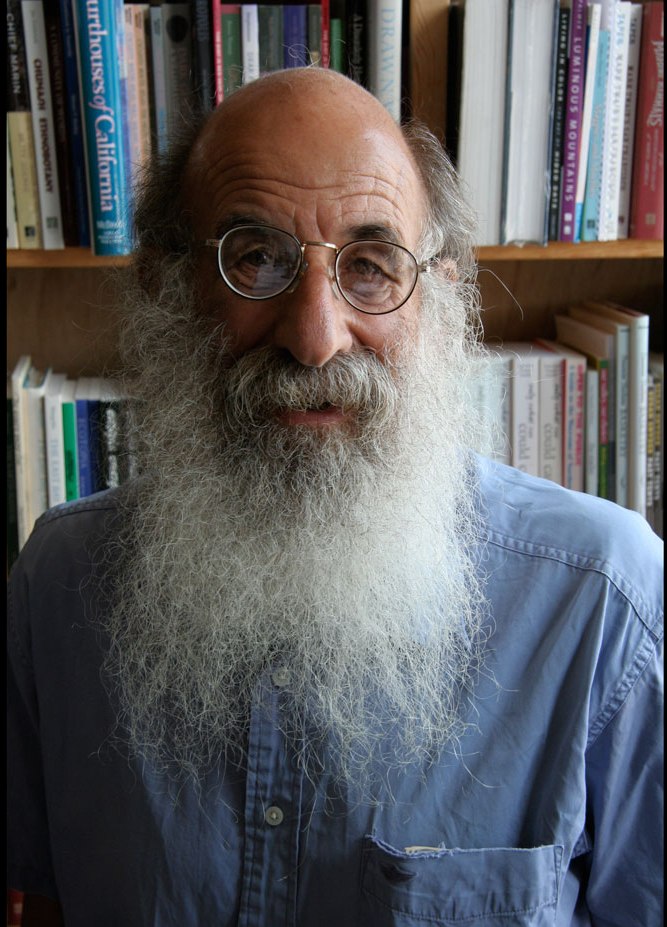

| Salman Rushdie at Frankfurt. |

"Limiting freedom of expression is not just censorship, it's an assault on human nature," said Salman Rushdie, author of Two Years Eight Months and Twenty Eight Nights, during the opening press conference of the Frankfurt Book Fair yesterday. Juergen Boos, the director of the fair, and Heinrich Riethmueller, chairman of the Börsenverein, the German publishers, wholesalers and booksellers association, also spoke at the press conference. The subject of discussion was the importance of freedom of expression for both authors and the book industry, an issue put into sharp perspective last week when Iran announced that it would boycott the book fair due to Rushdie's presence as a guest speaker.

In his remarks, Boos acknowledged the Iranian boycott, saying he was not happy about it and he regretted that it took away an opportunity to exchange opinions with Iranian colleagues. But it was "non-negotiable," he said, that freedom of expression and freedom of opinion be protected. Added Boos: "Our ideas cannot be killed."

Rushdie, who has lived under the threat of an Iranian fatwa since 1989, recalled his first visit to the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1998. His surprise appearance at that year's opening ceremony was one of his first public appearances after the fatwa. That earlier visit, he remembered, "induced a great feeling of optimism" in him about the future of the book world, and made him see that publishing was both the "embodiment and guardian" of freedom of speech.

"I've always thought in a way we should not need to discuss freedom of speech in the West," said Rushdie. "This should be like the air we breathe." And yet, lamented Rushdie, despite the battle for free expression having been won in the West "a couple hundred years ago" by writers in the Enlightenment, people must continue to fight for it.

Threats of violence and actual violence against writers, publishers and translators have engendered a "not unjustified" fear in those in the book world. In Rushdie's estimation, publishing, which is a peaceful business, begins to feel like a war. "Publishers and writers are not warriors," said Rushdie. "But it falls to us to hold the line."

Violence, continued Rushdie, was not the only problem currently facing the world of words. He brought up the story of a planned seminar about free speech at a university in England, which saw two invited speakers blocked by the university's student union. People claiming to stand for the virtue of free speech, Rushdie said, had "demolished what they stand for." He also touched on the controversy surrounding incoming freshman at Duke University refusing to read Alison Bechdel's graphic novel Fun Home because they felt its content would offend their religious upbringing, as well as the broader push for the use of trigger warnings at institutions of higher education. Asserted Rushdie: "The idea that students should not be intellectually challenged at universities is the exact opposite of what universities are for."

But perhaps the most powerful attack against freedom of expression, said Rushdie, was the idea put forth in some non-Western countries that "freedom of expression is culturally specific" and that Western cultures may support it but that people in other parts of the world "reserve the right to reject it."

.jpg) |

| Copies of the German translation of Rushdie's newest book. |

Freedom of expression, countered Rushdie, was not culturally specific but a "universal principle" based on human nature. Expression and speech is fundamental to all human beings. "We are language animals," said Rushdie, and not only language but narrative. "We are the storytelling animal." Humans understand their own lives through multiple layers, or a "concentric circle" of continuing narratives, with the narrative of the individual at the center, surrounded by the narratives of the family, the community, the city, the country, and so on.

"Through those narratives we understand ourselves," he said. "It happens wherever in the world we are."

Rushdie shied away from prescribing a societal role to all writers, but said that he was "unable to exclude public matters" from his work. As a child of the 1960s, he was left with the idea that people are "not helpless creatures in the grip of large forces, but by our choices and our deeds could affect the world in which we live."

He also rejected the notion of a "shared description of the world" between writer and reader. That assumption, he said, was the bedrock upon which the realist novel was built in the 19th century, but it was no longer true. Today, reality is "hotly contested," and all across the world there are "incompatible narratives fighting for the same patch of earth."

"We can't assume there is such a thing as uncontested realism," he said. "Fiction contests the world."

Rushdie noted that though writers are fragile things as individuals, their work can be immensely powerful. The poetry of Ovid outlasted the Roman empire, he said, and the poetry of Osip Mandelstam survived the Soviet Union, but the longevity of literature is little consolation to a writer being persecuted in the present. "We should protect writers as much as writing," he urged, and not "wait to be justified by some distant posterity."

Rushdie ended with a reminder that the main opponent of Enlightenment thinkers in the fight for free expression was not the state but the church. He can share these thoughts at a press conference, he said, because "writers in France 200 years ago defeated the power of the church." What we see today, he said, is the renewal of that same argument with different churches and different religions. And though it may be the same argument, it's "just as important to win it." --Alex Mutter

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.S1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

.jpg)

On December 11, 1973, 19-year-old Mark Segal disrupted a live broadcast of the CBS Evening News when he sat on the desk directly between the camera and news anchor Walter Cronkite, yelling, "Gays protest CBS prejudice!" He was wrestled to the studio floor by stagehands on live national television. Some 42 years later, the New York launch party for Segal's And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality (Akashic) was held at the same building, which now houses NBC Studios. Pictured are Segal with original members of Gay Youth, the first organization to deal with the issues of gay and endangered LGBT teens, founded in 1969.

On December 11, 1973, 19-year-old Mark Segal disrupted a live broadcast of the CBS Evening News when he sat on the desk directly between the camera and news anchor Walter Cronkite, yelling, "Gays protest CBS prejudice!" He was wrestled to the studio floor by stagehands on live national television. Some 42 years later, the New York launch party for Segal's And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality (Akashic) was held at the same building, which now houses NBC Studios. Pictured are Segal with original members of Gay Youth, the first organization to deal with the issues of gay and endangered LGBT teens, founded in 1969.

Upright Beasts

Upright Beasts

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for: Seventeen-year-old Calvin's first baby gift was a stuffed tiger named Hobbes, his best friend is named Susie, and he was born the very same day Bill Watterson's last Calvin and Hobbes comic was published. It's little wonder, then, that he thinks he actually is the blond-haired Calvin from Calvin and Hobbes come to life. And that would also explain why Hobbes the tiger is actually talking to him in "a full-on voice that didn't seem to have anything to do with me." As supportive and dryly entertaining as Hobbes can be, Calvin hates that he talks to him, because that pretty much clinches the fact that he is mentally ill.

Seventeen-year-old Calvin's first baby gift was a stuffed tiger named Hobbes, his best friend is named Susie, and he was born the very same day Bill Watterson's last Calvin and Hobbes comic was published. It's little wonder, then, that he thinks he actually is the blond-haired Calvin from Calvin and Hobbes come to life. And that would also explain why Hobbes the tiger is actually talking to him in "a full-on voice that didn't seem to have anything to do with me." As supportive and dryly entertaining as Hobbes can be, Calvin hates that he talks to him, because that pretty much clinches the fact that he is mentally ill.