Arnaud Nourry, chairman and CEO of Hachette Livre, joined Hachette in 1990, and since his appointment as CEO in 2003, has overseen the company's expansion into markets outside of France.

Arnaud Nourry, chairman and CEO of Hachette Livre, joined Hachette in 1990, and since his appointment as CEO in 2003, has overseen the company's expansion into markets outside of France.

Speaking yesterday at the Frankfurt Book Fair with publishing consultant Ruediger Wischenbart and answering questions from trade journalists, Nourry explained that in 2003, he reached the conclusion that to continue to deliver stable profits, Hachette Livre had to grow, but due to scrutiny from the European Commission about Hachette's market share in France, the company could not expand in its native country. Given that Hachette already had operations in Spain and the U.K., Nourry concentrated his efforts there first, and then, with the acquisition of Time Warner Book Group in 2006, entered the U.S. market. Nourry doubted that he would have shareholder support for any major acquisitions at present, but he said that medium-sized acquisitions would "remain very active." On the topic of Hachette's ultimately unsuccessful bid to buy Perseus last year and whether Hachette may try again now that Perseus is up for sale, Nourry said he could not comment.

.JPG) |

| Arnaud Nourry at Frankfurt |

When asked if he expected any more major consolidation in the publishing industry on the order of the Penguin Random House merger, Nourry doubted that it would happen soon, but, he said, "down the road there will certainly be more consolidation."

After the e-book market in the U.S. was brought up, Nourry jokingly wondered if anyone from the Department of Justice were in the room. Asked if he still worried about the possibility of low e-book prices devaluing books in consumers' minds, Nourry replied that publishers "have to be very careful" and "never think that it's behind us."

Publishers have learned from the music and magazine industries, Nourry continued, that "when you lose control of the price point for your content, you are on your way to death." Book publishers, he said, "must have some control" of price points, whether through laws or contract negotiations. He has been convinced since day one, he added, of the need to make sure that the "value of our content would not be depreciated by others." Nourry also doubted that he was alone on this point. By looking at what other publishers have been doing in the U.S. and U.K., the consensus seemed to be that major publishers should keep control of prices.

Nourry also addressed the plateauing and slight dropping off of e-book sales within the United States. The conclusion his company has reached, he said, was that the e-book market so far has been one based almost entirely on e-ink devices sold particularly to avid readers. That population now is saturated--there is no growth potential, he continued, among heavy readers for e-ink devices. In his view, that explained the plateau, and the increase in e-book prices in recent years might explain why a slight decline has followed that plateau.

"I think the same will happen in the U.K.," Nourry said, noting that the U.S. and U.K. were the only to countries to have such wide, deep penetration of e-readers. He believed that the much slower of adoption of e-readers in continental Europe was the result of no retailer being able to offer both an affordable device and massive discount on content.

Nourry said he would remain "quite silent" on the topic of Hachette's very public dispute with Amazon last year, but did offer: "I think there were two options for Amazon and ourselves. Do we keep accepting deep discounting, or do we go back to agency?" The conflict came because Amazon was more in favor of the first option, while Hachette preferred the latter, and "the rest is history."

On the topic of proposed changes to digital copyright laws in the European Union, Nourry said that the "naive desire of creating a unified digital market" in Europe was at present his "biggest concern." Nourry wondered why the European Commission would attack the only media and cultural industry in which Europe is powerful, and said he believed that behind the scenes this was in fact a battle between some major American technology companies and European officials.

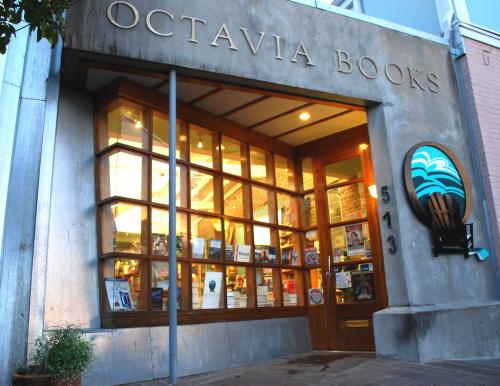

Nourry did not equivocate when asked if he saw a future for print books. "I think the answer is obvious that there is a bright future," he replied, and brought up the resurgence of independent bookstores in the U.S. as a sign of hope. During his last trip to BookExpo America, he recalled, the independent booksellers he met with were quite optimistic, while the buyers for big box retailers were the ones who were afraid. As long as independent booksellers "don't forget they are businessmen," Nourry added, they are in a position not only to survive but thrive.

Later in the discussion, Nourry said that he did not feel threatened by the ever-growing self-publishing industry, seeing it as "the contrary [opposite] of my business." While there are some proven authors who decide to self-publish, the vast majority of self-published authors, he said, are those "who have not found a way to a traditional publisher." He did acknowledge that sometimes, as with E.L James's Fifty Shades of Grey series, traditional publishers get it wrong, but he was quick to note that James had even greater success after signing a deal with a traditional publisher.

In the panel's q&a portion, Nourry addressed his company's direct-to-consumer efforts, saying that "we don't want to be retailers," but DtoC does help decrease Hachette's dependency on major companies that "may have a tendency to impose painful terms on us." --Alex Mutter

"Our focus this year on finding the world's best bookstore aims to highlight the absolutely vital role bookshops play worldwide in not only promoting new titles but also advising readers on the many excellent books already published but yet to be discovered. We look forward to hearing about the many initiatives being undertaken by colleagues around the world which showcase the best in publishing."

"Our focus this year on finding the world's best bookstore aims to highlight the absolutely vital role bookshops play worldwide in not only promoting new titles but also advising readers on the many excellent books already published but yet to be discovered. We look forward to hearing about the many initiatives being undertaken by colleagues around the world which showcase the best in publishing."

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.S1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

Arnaud Nourry, chairman and CEO of Hachette Livre, joined Hachette in 1990, and since his appointment as CEO in 2003, has overseen the company's expansion into markets outside of France.

Arnaud Nourry, chairman and CEO of Hachette Livre, joined Hachette in 1990, and since his appointment as CEO in 2003, has overseen the company's expansion into markets outside of France..JPG)

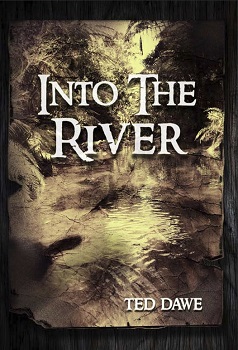

The Interim Restriction Order

The Interim Restriction Order

Geraldine Brooks, author most recently of The Secret Chord and host this month of the WSJ Book Club, has

Geraldine Brooks, author most recently of The Secret Chord and host this month of the WSJ Book Club, has

Congratulations to

Congratulations to  Long Story Short: The Only Storytelling Guide You'll Ever Need

Long Story Short: The Only Storytelling Guide You'll Ever Need The

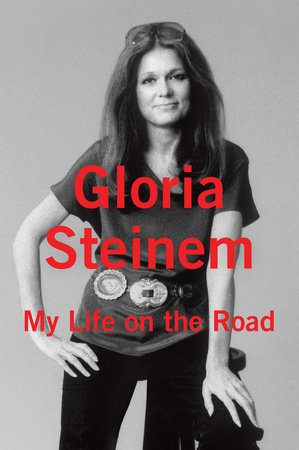

The  Gloria Steinem, founder of New York and Ms. magazines and many women's organizations and a noted leader of the women's movement, shares her stories from along the way in My Life on the Road. This simply stated memoir recounts Steinem's childhood, her organizing and activism from her youth into the present, with commentary on the social and political events of those decades. But it is also explicitly a story of life lived on the move. As she sees it in hindsight, Steinem inherited a love for constant motion from her father, who lived for most of her life out of his car, with little Gloria keeping him company for her first 10 years. As a young woman not ready to settle down to marriage and motherhood, and then as an organizer, she kept moving. One chapter is dedicated to her choice to travel communally rather than use an automobile of her own, because it offers increased opportunities for contact.

Gloria Steinem, founder of New York and Ms. magazines and many women's organizations and a noted leader of the women's movement, shares her stories from along the way in My Life on the Road. This simply stated memoir recounts Steinem's childhood, her organizing and activism from her youth into the present, with commentary on the social and political events of those decades. But it is also explicitly a story of life lived on the move. As she sees it in hindsight, Steinem inherited a love for constant motion from her father, who lived for most of her life out of his car, with little Gloria keeping him company for her first 10 years. As a young woman not ready to settle down to marriage and motherhood, and then as an organizer, she kept moving. One chapter is dedicated to her choice to travel communally rather than use an automobile of her own, because it offers increased opportunities for contact.