My first question for Vanessa Diffenbaugh is "Which flower says "I'm sorry?"--our interview had to be rescheduled twice. Diffenbaugh's already much-buzzed debut novel, The Language of Flowers (Ballantine), concerns exactly that--the "language of flowers" that was particularly popular in the Victorian era.

Diffenbaugh is a Stanford-educated novelist and charity founder (the Camellia Network, which provides support for young people leaving the foster care system) who is married with two small children.

Wait, make that four children: Diffenbaugh and her husband, PK, are also parents to 18-year-old Tre'von and 21-year-old Donovan, both of whom are foster children. Since The Language of Flowers is about a young woman named Victoria who has lived her entire life in the foster-care system, Diffenbaugh is clearly writing about something she knows. But how and when did she decide to become a foster parent?

"Both my husband and I were raised by parents who were products of the counterculture, and really believed in social justice and equality. I remember being at rallies with my father that he helped organize for Jesse Jackson and the Rainbow Coalition, and PK's family actually founded an orphanage in India where they spent several months out of each year. We both are completely focused on service," she explained.

Diffenbaugh knew she wanted to be a foster parent early on, around age 21. "I'd been working in restaurants after graduating from Stanford. It was the time of the total dotcom boom, and I knew I wanted more meaning in my life than just money. We knew we should get a house and settle down and all those things, but.... We did make some mistakes along the way."

The first was taking two girls who were sisters, ages three and 13. "I thought we were ready, and I'd asked for one school-aged child," Diffenbaugh said. "We figured that with both of us working full-time jobs, we could provide a good environment. But we weren't prepared for the fact that once you're approved as a foster parent, they call you every day--and you're in it because you want to help someone, so you agree to situations that aren't ideal because the kids are in such need."

After a couple of weeks, they had to return the girls. "It was incredibly hard," Diffenbaugh admitted. "But I just couldn't handle it. And then, a little while later, came a girl who was very much like my character Victoria. She was 15 and really troubled, and my husband really wanted to adopt her. He was fully committed to that adoption, but I was pregnant with our first biological child, and I couldn't make that commitment. The fallout was awful, a terrible emotional dance between her and me."

Diffenbaugh continued: "Part of what I was trying to do with this book was to show the depth of character that exists even in the most difficult, troubled, unreachable child. They can be violent and angry and all of these terrible things, but I believe every child has the capacity to love and be loved. The journey to that capacity is possible when we allow ourselves to be open to other beings."

Reaching children before they grow up is crucial, too, because, as Diffenbaugh points out, 60% of our nation's homeless people spent time in the foster-care system. "A lot of people ask why I write fiction rather than nonfiction, and it's because I want to reach as many people as possible," she added. "I don't know a lot of readers who would walk into a bookstore and pick up a nonfiction book about a traumatized kid, but through fiction, you can tell and read that story in the first person and learn from it, without things becoming too heavy handed."

That's no small feat, since there is parts of The Language of Flowers are very sad, especially after Victoria has a baby. "It's something I hope to speak about more when I'm on tour," Diffenbaugh said. "I could only write two to three sentences at a time in those places, because it's so wrenching to put yourself in the head of someone who is about to abuse or neglect her baby. She wants so desperately to love and care for her child, but she just doesn't know how."

How did the "language of flowers" work into the story? "At that age, knowing something that no one else knows is a very powerful feeling. I needed a way for Victoria to communicate, and this was perfect, in that it had a feeling of secrecy, but also connected her to the one foster parent in her life, Elizabeth, who really reached her."

But Diffenbaugh isn't planning to write about flowers--or foster care--again. "I want to write fiction that allows me to explore a social issue I care about, and in my next book, I'm already on that path," she said. "I want to be the best writer I can be, but I also want to reach people, to have a message that is deep and powerful communicated in language that is simple and straightforward."

It's time to end our call, and so I thank Diffenbaugh and apologize one more time. "I just remembered the perfect flower for an apology," she answered. "Purple hyacinth means 'please forgive me.' "

We've already been speaking the same language. --Bethanne Patrick

Portrait of the Artist: Vanessa Diffenbaugh

Late August: I recommend an earthy pairing: The Call by Yannick Murphy and The Leftovers by Tom Perrotta. Don't forget your hip boots and rapture garments!

Late August: I recommend an earthy pairing: The Call by Yannick Murphy and The Leftovers by Tom Perrotta. Don't forget your hip boots and rapture garments!

As the 10th anniversary of September 11, 2001, approaches, we’ve been thinking a lot about how to prepare children for the images they'll be seeing. Many children were either too young to process what was happening at the time or were not yet born. Pictures and accounts from that day may be confusing to them. America Is Under Attack: September 11, 2001: The Day the Towers Fell by Don Brown does a terrific job of reporting the day's larger events and also telling the stories of several individuals, to put human faces on the staggering number of people affected.

As the 10th anniversary of September 11, 2001, approaches, we’ve been thinking a lot about how to prepare children for the images they'll be seeing. Many children were either too young to process what was happening at the time or were not yet born. Pictures and accounts from that day may be confusing to them. America Is Under Attack: September 11, 2001: The Day the Towers Fell by Don Brown does a terrific job of reporting the day's larger events and also telling the stories of several individuals, to put human faces on the staggering number of people affected. 14 Cows for America by Carmen Agra Deedy, illustrated by Thomas Gonzalez (Peachtree). Accompanied by glorious images of the Kenyan landscape, Deedy tells the true story of a Maasai tribe member who was attending medical school in the U.S. when the planes hit on 9/11. He returns to his village to ask his tribal elders if he can dedicate his sacred cow to America, to heal them from their great sorrow. The tribe is so moved by his story that they dedicate 13 additional cows for America. The book is ideal for youngest children because the storyteller must help his fellow villagers understand the magnitude of the event ("Smoke and dust so thick they can block out the sun," he tells them), and also because of its healing message.

14 Cows for America by Carmen Agra Deedy, illustrated by Thomas Gonzalez (Peachtree). Accompanied by glorious images of the Kenyan landscape, Deedy tells the true story of a Maasai tribe member who was attending medical school in the U.S. when the planes hit on 9/11. He returns to his village to ask his tribal elders if he can dedicate his sacred cow to America, to heal them from their great sorrow. The tribe is so moved by his story that they dedicate 13 additional cows for America. The book is ideal for youngest children because the storyteller must help his fellow villagers understand the magnitude of the event ("Smoke and dust so thick they can block out the sun," he tells them), and also because of its healing message. Ladder to the Moon by Maya Soetoro-Ng (sister of President Obama), illustrated by Yuyi Morales (Candlewick) also takes more of a symbolic approach to 9/11, as a girl and her grandmother reach down to children on earth who are in peril and invite them up to safety with them on the moon. Author and artist together create abstract images of a tsunami, 9/11 and war and focus on themes of love and security.

Ladder to the Moon by Maya Soetoro-Ng (sister of President Obama), illustrated by Yuyi Morales (Candlewick) also takes more of a symbolic approach to 9/11, as a girl and her grandmother reach down to children on earth who are in peril and invite them up to safety with them on the moon. Author and artist together create abstract images of a tsunami, 9/11 and war and focus on themes of love and security. The Man Who Walked Between the Towers (Roaring Brook Press) is Mordicai Gerstein's 2004 Caldecott Medal-winning picture book about Philippe Petit's amazing tightrope walk between the World Trade Center towers in 1974. Gerstein pays tribute to the architectural feat of the towers as well as Petit's accomplishment.

The Man Who Walked Between the Towers (Roaring Brook Press) is Mordicai Gerstein's 2004 Caldecott Medal-winning picture book about Philippe Petit's amazing tightrope walk between the World Trade Center towers in 1974. Gerstein pays tribute to the architectural feat of the towers as well as Petit's accomplishment. Fireboat: The Heroic Adventures of the John J. Harvey (Penguin/Puffin) by Maira Kalman pays tribute to the John J. Harvey, a fireboat that came out of retirement to aid New Yorkers on September 11, 2001. The fireboat’s story begins at its launch in 1931, during Manhattan's glory days, when the Empire State Building and George Washington Bridge were going up and Babe Ruth hit his 611th home run. But as the piers start to close, the fireboat's days dwindle, until a group of friends rescue the boat, and the John J. Harvey in turn proves itself the little fireboat that could for New Yorkers in need on their darkest day.

Fireboat: The Heroic Adventures of the John J. Harvey (Penguin/Puffin) by Maira Kalman pays tribute to the John J. Harvey, a fireboat that came out of retirement to aid New Yorkers on September 11, 2001. The fireboat’s story begins at its launch in 1931, during Manhattan's glory days, when the Empire State Building and George Washington Bridge were going up and Babe Ruth hit his 611th home run. But as the piers start to close, the fireboat's days dwindle, until a group of friends rescue the boat, and the John J. Harvey in turn proves itself the little fireboat that could for New Yorkers in need on their darkest day. The Borders Group Foundation, an independent charity created in 1996 that has distributed more than $5 million to Borders employees in difficult straits, says it will "continue to serve and support former Borders associates experiencing an unexpected financial need." Unfortunately this apparently doesn't include unemployment; grants are for "unforeseen emergencies such as death of a family member, divorce or legal separation, natural disaster, disability, serious medical condition and crime." [Editor's note: perhaps "crime" does cover what happened to Borders.]

The Borders Group Foundation, an independent charity created in 1996 that has distributed more than $5 million to Borders employees in difficult straits, says it will "continue to serve and support former Borders associates experiencing an unexpected financial need." Unfortunately this apparently doesn't include unemployment; grants are for "unforeseen emergencies such as death of a family member, divorce or legal separation, natural disaster, disability, serious medical condition and crime." [Editor's note: perhaps "crime" does cover what happened to Borders.] Flavorwire offered a

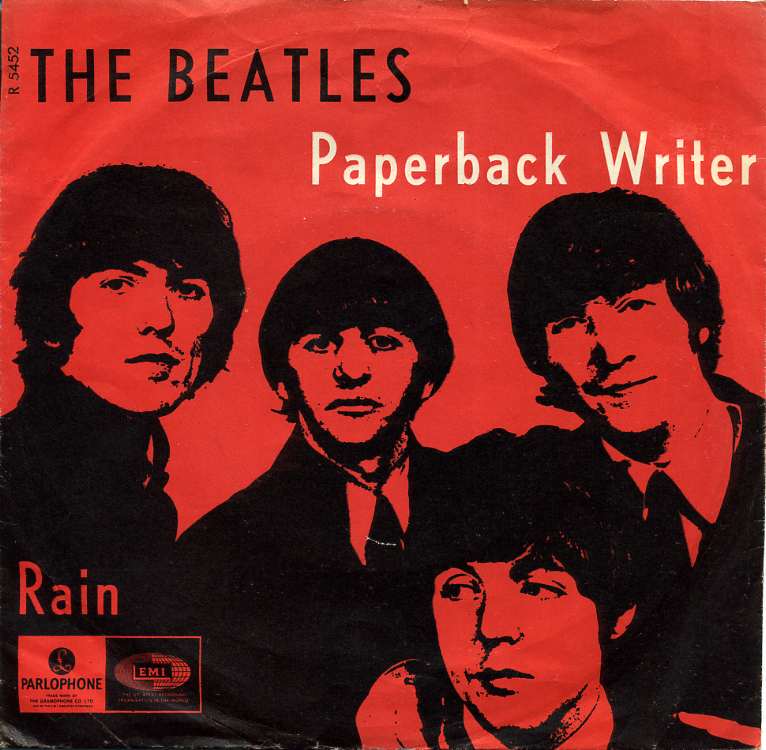

Flavorwire offered a  We've all listened to "Paperback Writer" by the Beatles. Some of us have sung along to it more times than anyone in our family would like to acknowledge. But until now, no one has formally responded to the plea the song's narrator makes: "It took me years to write/ Will you take a look?"

We've all listened to "Paperback Writer" by the Beatles. Some of us have sung along to it more times than anyone in our family would like to acknowledge. But until now, no one has formally responded to the plea the song's narrator makes: "It took me years to write/ Will you take a look?"