_Megan_Sembera_Peters.jpeg) |

| photo: Megan Sembera Peters |

Jill Alexander Essbaum is the author of several collections of poetry and her work has appeared in The Best American Poetry and in The Best American Erotic Poems, 1800-Present. She is the winner of the Bakeless Poetry Prize and recipient of two NEA literature fellowships. She teaches at the University of California, Riverside's Palm Desert Low-Residency MFA program, and lives in Austin, Tex. Essbaum's debut novel, Hausfrau, was just published by Random House.

Hausfrau is your first novel, but not your first book. How was crafting this book different than writing poetry?

Honestly? The biggest difference was that I had to keep my rear end in the chair for a longer amount of time! That's pretty much it (notwithstanding such pesky details like plot and setting and character, of course).

The poems I tend toward, while not perfectly formal, are formal-ish, and employ many traditional devices (rhyme, meter, anaphora, the works). For me, a poem is as dependent on structure as it is on both subject matter and the words the poet chooses to make the poem. Hausfrau doesn't rhyme, of course, but there's an overriding structure to it that serves the book in the manner that, say, the tha-THUMP of the iambic meter and the aural markers of the repeated rhymes and the just-past-the-eighth-line turn serve a Petrarchan sonnet. They are tethers, guy wires, mile markers, fences. For example, in Hausfrau, each section lasts exactly one month and contains a birthday party. The lines that describe Anna's first interaction with one of her lovers are repeated in an entirely different context at a key point later in the narrative. I hope this isn't just me waxing clever. Structure should serve to shepherd a reader through the book. It certainly shepherded me through the writing of it.

You open the novel observing, "Anna was a good wife, mostly." What interested you in writing about a character, like Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary before her, whose happiness appears to be at odds with her "good"-ness?

I'm not sure I was interested in writing about a character as such. I was interested in writing about Anna. Poor, unfathomable, busted Anna. She's the heartbeat of the book and from the moment I started to write her I knew we belonged to each other. I don't condone her or support her or endorse her--but I understand her. Above all else I think Anna needs someone to wholly understand her. And as stupidly as she behaves, and as terribly as she chooses to act (both in and out of consciousness), there are moments when a true goodness breaks through. For example, setting aside a particularly awful moment, her relationship with her son, Charles, is almost excruciatingly tender. I desperately want her to be okay. But she doesn't let anyone help her. Not even me.

Anna, an American, lives in a Zürich suburb with her Swiss husband and their child. Why did you choose to set the events of the novel there?

Anna, an American, lives in a Zürich suburb with her Swiss husband and their child. Why did you choose to set the events of the novel there?

Zürich is the city that best represents Swiss strictness, I think. The to-the-penny ledgering of the banking industry, the tick-tock precision of the clocks and all those omnipresent, on-time trains! Also, it's the seat of both the International School of Analytic Psychology and the C.G. Jung Institute, the former of which was the school that my then-husband attended when we expatriated to Switzerland. And once I started to write the book, I understood there could be no other setting.

Were you writing this while in the country, or did you return for further research? Do you have a favorite place there to visit?

No. I started to write this once I moved back to Texas. I was very unhappy in Switzerland and in many ways (except I don't have children and did not have a series of love affairs!) I lived an Anna-esque life: I didn't have a job. I didn't drive a car. I had very few friends and spent a lot of time roaming the woods behind the little town we lived in trying to figure out what I was going to do with the rest of my life. I was there with my then-husband, who, as I mention, attended school. His life was contextualized with a specific purpose. Mine was not. So when I returned to Texas it was "good riddance, Switzerland!"

But I didn't get rid of it. For as miserable as I had been, as lonely and as bored and as sad, all that wandering and walking, aimless train riding and grocery-store prowling, had done something to me that couldn't be undone. I didn't hate Switzerland at all. I loved it. So every detail I wrote, I relived. I offer this book as a love letter to Switzerland. I'll never live there again. But it lives in me.

I've been back once and I plan to go again once the book is out. I've remarried and I'd like to take my husband there. I want to re-hike those woods. I want to sit on my bench. Anna's bench is really my own. I'll probably cry. But it will be a good cry.

You brilliantly call the reader's attention to the nuances of language throughout the story--like when Anna asks, "Is there a difference between shame and guilt?" or when her Swiss German teacher notes that the German word Bad "doesn't mean 'not good,' it means 'bath.' " Why delve so deeply into these subtleties in your novel?

Here's what I tell my poetry students when they come to me and say, "I have an idea for a poem and it's..." (which they've learned to no longer do, as they are tired of this broken-record speech): Poems aren't made of ideas or concepts. They're built of words. That's it. Dumb old words. Some will argue this--and I'll give them their space for that--but I will never privilege a concept over its concretization. And in writing, the concretization of concepts is accomplished by language.

But it goes beyond that. Consider: the tiniest knots in a handcrafted piece of needlepoint. The intricacies of inlaid stonework. The ornamental grace note. Those codes that can only be unencrypted when you unzip a strand of DNA. The devil's not in the details. Detail is all god. The closer you look at a thing, the more complex it becomes. There's nothing truer or more beautiful than that.

Much of your poetry and a significant (ahem) thrust of Hausfrau has to do with sexuality. How do you write about sex without straying into the comical or gratuitous realms that have landed so many authors in the running for the Bad Sex in Fiction Award?

Easy. I asked for advice. (And thank you for NOT nominating me for a Bad Sex in Fiction Award!) One of my colleagues--novelist and nonfiction writer Mark Haskell Smith--gave me the skinny: un-purple all prose. Be straightforward. If it throbs or heaves, then save it for the bodice-rippers. It has no place here. It was incredibly wise counsel.

Throughout the book, Anna visits her psychoanalyst, Doktor Messerli, while attempting to understand better her pervasive discontentment. Have you always been interested in Jungian psychology, or did you research this especially for this book?

I've been seeing an analyst for a long time. My ex-husband was in analysis as well and that's what sent him to Zürich to pursue analytic training.

We did a funny thing recently, my analyst and I, during a session. We tried to diagnose Anna. DSM-V and all. In the end, here's what we came up with: She is very, very, very, very sad. And she acts most often from a place of unconsciousness. Which rarely ends well.

Which authors' work or books inspired or helped you write Hausfrau?

It's irresponsible for me not to mention this every time I'm asked and I'm glad to repeat it: the book is, in part, an homage to Madame Bovary. I emphasize in part because it really isn't a retelling. What I hoped to recall was the set-up of the novel, if you will: once upon a time, a woman married a man that maybe she shouldn't have (or should have--who's to say?) and moved to a place where she never felt like she belonged and so to temper her inner discomfort she has her first affair which leads to another which leads to another until she finds that she simply can't stop herself. But Anna isn't Emma. After that point, I think Hausfrau becomes its own book.

I'm indebted to Donna Tartt's The Secret History, which I probably read four or five times during the writing of Hausfrau. That book is a master class in pacing and how to let a story tell itself.

Josephine Hart's Damage taught me suspense and brevity. Joyce Carol Oates, Jeanette Winterson, Patricia Highsmith--I read a lot of women whose books bite back.

Hausfrau is such a terrific novel. Can we expect more fiction from you soon, or are you back into (your equally terrific) poetry mode for the foreseeable future?

I have a book of poetry that's been haranguing me to finish it for a couple of years. There's also a craft book I'm forever threatening to write (like, the craft of poetry, I mean, not macramé or making hook rugs). Fiction-wise, I'm writing around a couple of things right now. The NBA. A psychological disorder called scrupulosity. Jesus. Free-throws. The usual. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness

Jill Alexander Essbaum: True Goodness Breaks Through

Since then, I've been a changed man and can't wait to see two of my favorite actors--Mark Rylance as Cromwell and Damian Lewis as Henry VIII--bring Mantel's world to life on Sundays at 10 p.m. from April 5 to May 10. (More is played by Anton Lesser, though he's buried in the cast list. No disrespect intended, I'm sure).

Since then, I've been a changed man and can't wait to see two of my favorite actors--Mark Rylance as Cromwell and Damian Lewis as Henry VIII--bring Mantel's world to life on Sundays at 10 p.m. from April 5 to May 10. (More is played by Anton Lesser, though he's buried in the cast list. No disrespect intended, I'm sure).

_Megan_Sembera_Peters.jpeg)

Anna, an American, lives in a Zürich suburb with her Swiss husband and their child. Why did you choose to set the events of the novel there?

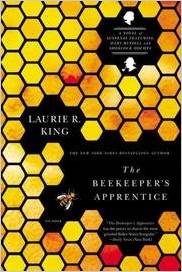

Anna, an American, lives in a Zürich suburb with her Swiss husband and their child. Why did you choose to set the events of the novel there? The Beekeeper's Apprentice, Or On the Segregation of the Queen (Picador) is the first novel in Laurie R. King's Mary Russell series. In it, the 15-year-old orphan Mary Russell meets the great detective Sherlock Holmes, who has retired to a quiet life of beekeeping in the English countryside. The pair immediately takes a liking to each other, and soon Mary is Holmes's apprentice. And not long after she begins her term at Oxford University, they must team up to solve a major case.

The Beekeeper's Apprentice, Or On the Segregation of the Queen (Picador) is the first novel in Laurie R. King's Mary Russell series. In it, the 15-year-old orphan Mary Russell meets the great detective Sherlock Holmes, who has retired to a quiet life of beekeeping in the English countryside. The pair immediately takes a liking to each other, and soon Mary is Holmes's apprentice. And not long after she begins her term at Oxford University, they must team up to solve a major case.