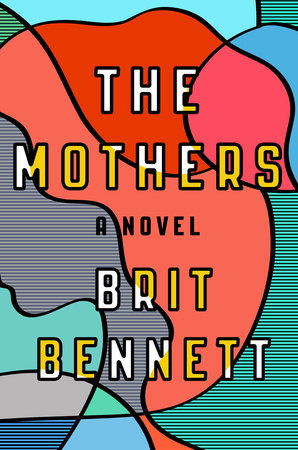

Independent booksellers across the nation have voted The Mothers, the debut novel by Brit Bennett (Riverhead, October 11), as their number one pick for October's Indie Next List.

Independent booksellers across the nation have voted The Mothers, the debut novel by Brit Bennett (Riverhead, October 11), as their number one pick for October's Indie Next List.

The "mothers" of the title refers to the elderly female members of Upper Room Chapel in Oceanside, California, whose favorite activities include gossiping about their fellow congregants. This pertains especially to the young trio of Nadia, Luke, and Aubrey, whose romantic entanglements provide much of the book's drama.

The Mothers also boldly takes on the concept of motherhood in all its forms, whether biological, lost, aborted, adoptive, or conflicted, said Jamie Thomas, manager of Women & Children First in Chicago, who calls Bennett's novel "an honest, modern, and triumphant book."

"This is a book about salvation," said Thomas. "Not the spiritual salvation that the gossiping, but well-intentioned mothers seek, but the kind that comes with self-acceptance and growth."

After graduating from Stanford University, Bennett, who is 26 years old and based in Los Angeles, received a fellowship from the University of Michigan's MFA program in fiction. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker and The Paris Review, among other publications.

How did you come up with the idea for The Mothers and its narrative of love and friendship, grief and loss, choice and regret, hypocrisy and redemption, and the complicated nature of small communities?

Brit Bennett: I think a lot of it came from growing up in the church as a child and spending time within the church community, observing the people around me and becoming interested in the young people who are part of these churches. We often think of churches as skewing older, but I went to churches where there were very active young adult and teen ministries. It was very interesting to me, how people come of age and go through adolescence and become adults within these sometimes very conservative church communities.

When writing about Upper Room, which you portray as a close, insular community populated by strong individual characters, did you draw from your own churchgoing experience?

BB: My mom is Catholic and my dad is Protestant, so I would go to either of their two churches depending on the week. My dad's church is much larger than Upper Room, which I based loosely on a church my friend went to. I wanted to write about a smaller church because to me that was a lot more interesting since it forces people to be around each other in ways that you can avoid when you go to a huge church. Fiction is interesting when people are not allowed to avoid each other, and I think that small towns can provide that scenario, as can other small communities like churches.

What were some of the ideas you wanted to explore in this book?

BB: I was interested in mothering as a verb, not necessarily as just a noun or who you are, and I was interested in the different ways that people can mother each other. I also wanted to explore what it's like to be a young girl who comes of age and grows into a woman and what it's like if your mother is not there to guide you through that.

I also wanted to write about how families are made and how families can be destroyed and the ways in which secrets can ripple through communities and through time and still continue to affect our lives as we grow older.

Your characters have very polarized opinions on the subject of abortion. What was it like to try to put yourself in the shoes of people with whom you might not necessarily agree?

BB: I didn't want to go too deeply into the politics of it, mostly because that can get very didactic. It's also just boring to read anybody who is trying to use fiction just to make some type of political argument. That being said, I understand that just the act of writing about abortion is political and the act of a character having an abortion is political, so it was something that was unavoidable.

It was a very interesting experience, putting myself in the position of all these different characters and how they think about this, because to everybody, their own views make sense. It became a balancing act of exploring the tension within the main character and the people around her, while not making it into some explicit political argument one way or the other.

Your book's depiction of men was interesting, specifically Luke's idea of himself as a father even though his child with Nadia is never born. What did you want to portray with the character of Luke?

Your book's depiction of men was interesting, specifically Luke's idea of himself as a father even though his child with Nadia is never born. What did you want to portray with the character of Luke?

BB: I think this is a side of the conversation about abortion that we often don't hear or it's a perspective that is often deployed in a manipulative or controlling way. It was something I had complicated feelings about: how much say should Luke have in the decision about abortion since it's not his body but it is still his child. Over time I think my depiction of him became more nuanced and more empathetic than when he initially began as this stereotypically callous young male who was just glad to have an escape from an "inconvenient" situation. I wanted to explore both how he could be more interesting and more complicated as a character.

What is the function of the reoccurring voice of the church "mothers" that appears every few chapters?

BB: In a small church community there is this division of power, since those who hold the power are male, but the majority of church members are often female. The "mothers" and their gossip works as a subversive power that is by nature sort of stealthy and secretive. We dismiss gossip in our culture as being trivial, but it can often convey information in a way that empowers people who don't have actual visible power.

These older women in this church, although they are pushed to the side, actually have the greatest power of all, which is to control the narrative. In the end, they are constructing a certain narrative that has actual implications for the church.

The collective voice of the mothers became part of the book late into the drafting process. Originally The Mothers was completely written in this close third person, but I started to locate this new voice that was gendered and aged and had a specific tone to it that I wanted to play around with more.

Who are some of the authors who have influenced you as a writer?

BB: I love Toni Morrison. I think she's the greatest living American author, which is probably not that controversial to say. James Baldwin's Go Tell It on the Mountain is a great church novel, and I think there's a similarity with my book in that the protagonists are characters in these very fervent and conservative church communities who are personally ambivalent toward religion.

I also really love Dorothy Allison, who wrote the coming-of-age novel Bastard Out of Carolina. I think she is so great at writing about things that are brutal in a very beautiful way, and I also admire the nuanced, complicated way she writes about these poor rural communities that people are very quick to dismiss. That's something I hope to emulate in my writing.

How did you feel when you learned that independent booksellers had selected your debut title as their top pick for the October Indie Next List? Have independent bookstores influenced your life in other ways?

BB: It was pretty surprising. It's my first book, so I don't know much about how a lot of this works with bookselling; I'm kind of learning as I go. When I found out from the Riverhead publicity team that I'd been chosen, I was very excited and honored to know that booksellers, of all people, who read a million books, were excited about mine.

Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor, Michigan, is one bookstore that is important to me. I've always felt very grateful for that space. They always reached out to our MFA program when we were students and let us have readings there, which I thought was so gracious because none of us even had books to sell. I remember reading in there from the novel before it was an actual novel, when I was still drafting it. They also have a really nice writing space. --interview by Liz Button for Indie Next List

Brit Bennett on The Mothers, October's #1 Indie Next List Pick

Independent booksellers across the nation have voted The Mothers, the debut novel by Brit Bennett (Riverhead, October 11), as their number one pick for October's Indie Next List.

Independent booksellers across the nation have voted The Mothers, the debut novel by Brit Bennett (Riverhead, October 11), as their number one pick for October's Indie Next List. Your book's depiction of men was interesting, specifically Luke's idea of himself as a father even though his child with Nadia is never born. What did you want to portray with the character of Luke?

Your book's depiction of men was interesting, specifically Luke's idea of himself as a father even though his child with Nadia is never born. What did you want to portray with the character of Luke?