|

| photo: Doug Knutson |

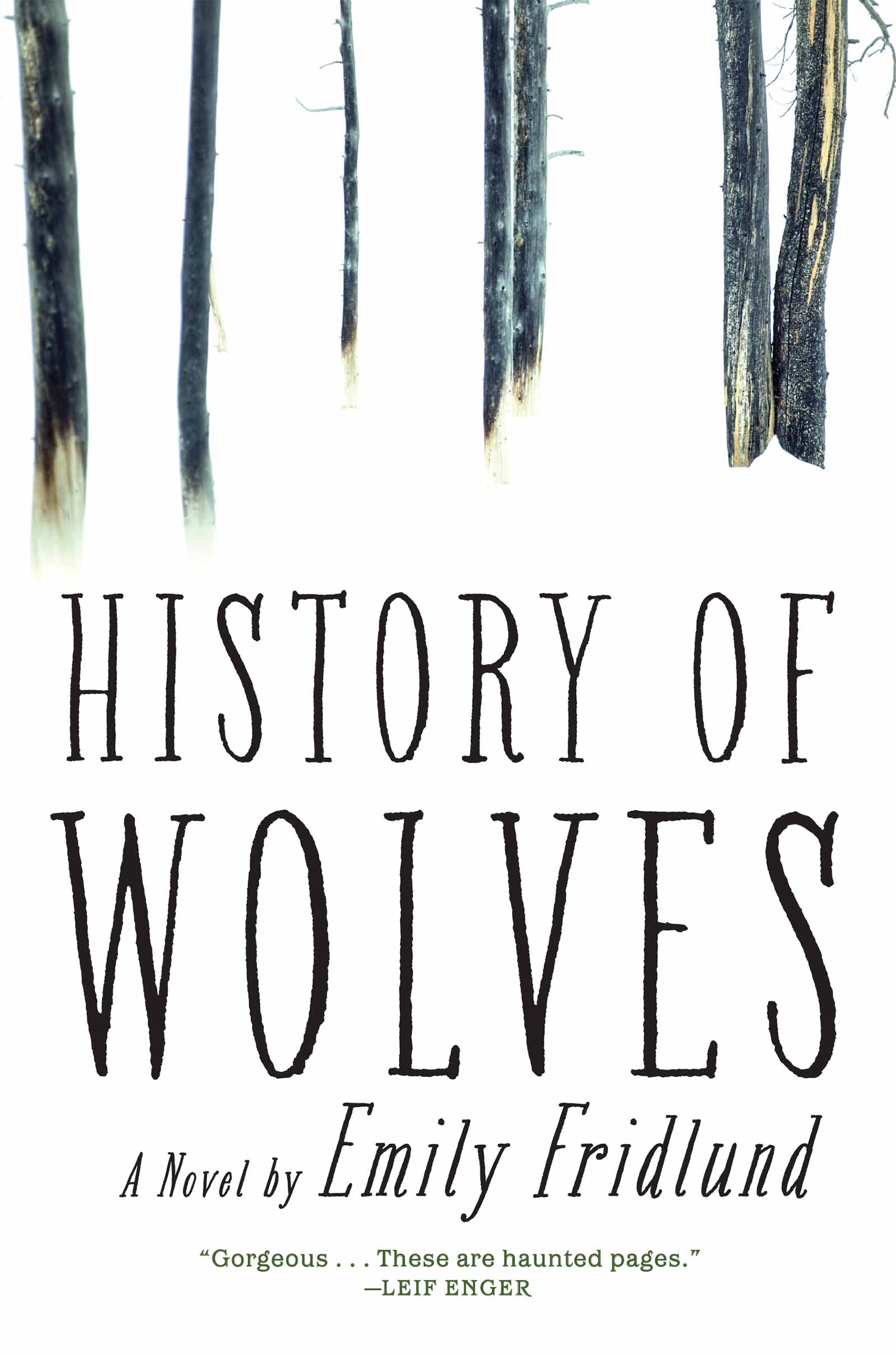

Independent booksellers have named History of Wolves: A Novel by Emily Fridlund (Atlantic Monthly Press) the number-one Indie Next List pick for January. Fridlund's debut was also chosen by booksellers for the Winter/Spring 2017 Indies Introduce program, and it was featured as an Editors' Buzz Book at BookExpo America 2016. The first chapter of History of Wolves won the Southwest Review's McGinnis-Ritchie Award for Fiction Prize in 2013.

Fridlund, who holds an MFA from Washington University and a Ph.D. in literature and creative writing from the University of Southern California, has been published in the Boston Review, the New Orleans Review, and the Portland Review, among other publications. Her stories have twice been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, and in 2015 Catapult, a collection of her short stories to be published next year by Sarabande Books, won the Mary McCarthy Prize.

Here, Fridlund discusses the inspiration for History of Wolves and what it means to have the support of indie booksellers for her debut novel.

History of Wolves began as a short story. Why did you decide to expand it into a novel?

I initially wrote the first chapter as a short story that focused on Linda's experiences at school and her relationship to her new teacher, Mr. Grierson. I wanted to think about issues related to desire and gender and power, and in particular what would happen if a sexual "predator" is himself pursued by an observant and lonely teenage girl. When I finished that story, I thought I was done with Linda and her austere northern Minnesota landscape. But I found there was something about Linda's voice that stayed with me. Because of her age and inexperience, there is a certain distance between what the reader knows and what she does, a gap that creates tension in the narrative. At the same time, those very same qualities that make Linda naïve--her isolation, her loneliness and youth--also make her an incredibly acute and natural observer of the world around her. She's paying fierce attention. Because she takes in all the details, she is often very good at reading people, even as she struggles, in her inexperience, to make sense of events as they unfold. I found this peculiar combination of canniness, ferocity, and ignorance compelling. I realized that lingering in Linda's voice a little longer might allow me to explore other ideas that interested me related to perception, belief, and storytelling.

The setting for History of Wolves--the bitter cold of northern Minnesota and the claustrophobic wilderness that Linda calls home--effectively becomes an additional character critical to the narrative. How did you prepare to write so extensively about Linda's world?

From the beginning, I thought of Linda's emotional landscape and northern Minnesota as closely linked. The novel's setting is based on a region of Minnesota I visited around the time the initial story expanded into a novel--somewhere west of Duluth, north of Brainerd--but it is also an invented place, based on Linda's unusual way of seeing and being in the world. The setting of the novel was, perhaps first and foremost, a way for me to get at and reveal my characters, Linda in particular. In the earliest drafts, I drew freely from my own experiences. I was a kid who loved being outside, roaming the scrappy suburban woods in my backyard and camping with my family up north. I was also inspired by my reading, especially Minnesota nature writers like Sigurd Olson and Helen Hoover, and also Barry Lopez's marvelous work on wolves. In later drafts I did more specific research into details like species and tools, but in the beginning so much of capturing Linda's voice was about capturing how she felt living in her world. That meant thinking of the setting as atmosphere as much as a concrete place.

As a main character, Linda is unusual: she is not particularly likable, she may be unreliable, her habits of watching people border on stalking, and she meticulously observes everything. How did you mold Linda as a character?

As a girl child raised at the end of the 20th century in the Midwest, I was trained to think a lot about likability, I admit. But as a reader and a writer it is not something that I think about much at all. I go to fiction for characters that are interesting, that make me think and feel in ways I haven't thought and felt before. I knew I could expand the short story that began History of Wolves when I realized that I found Linda's mode of being in the world interesting enough to engage me for the time it would take to write a book. One of the things that intrigued me most about Linda was her particular combination of canniness and innocence, which makes her powerful in some ways and helpless in others. She sees some things that the novel's other characters fail to take in, and at the same time her inexperience and isolation make her blind to certain patterns that might otherwise seem obvious. I was also drawn to Linda as a narrator because, unlike me, she lives a very physically demanding life. She spends her days chopping wood and fishing and keeping the fire going at night, and because of this, she is a person who experiences the world through her body rather than through talk or conversation. It was a challenge for me as a writer to situate her emotional responses within physical sensations, to let the reader see how she feels through her interactions with her dogs and the woods. It is maybe this aspect of Linda's character that makes the world around her seem a little charged.

Family is a murky theme in History of Wolves, and Linda exhibits an urgent sense of needing to belong. When she becomes the governess for the Gardner family, she nearly achieves that, but she's still stuck on the periphery. Why is the feeling of belonging so important to Linda?

Family is a murky theme in History of Wolves, and Linda exhibits an urgent sense of needing to belong. When she becomes the governess for the Gardner family, she nearly achieves that, but she's still stuck on the periphery. Why is the feeling of belonging so important to Linda?

Just before I wrote this novel I spent time reading some of the old great Gothic governess stories, books like Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre and Henry James' The Turn of the Screw. What I love about these books is the curiously peripheral-yet-essential role the governess plays in family structures. Because of this littoral zone the governess occupies, these books are especially good at teasing out issues related to power and powerlessness, or to maintaining the status quo and rebelling against it. The contemporary equivalent of the governess is the babysitter, of course, and Linda's role as babysitter to Paul in History of Wolves grants her privileged access to a family structure that she has been--because of her parents' commune past--denied. She wants what the people who raised her have eschewed: a fixed and reliable family. But her sense of belonging as a babysitter in the Gardner family is extremely fragile and temporary, and it comes with little reward and at a high price.

It's worth saying, too, that I don't think of this predicament as especially unique to Linda. Don't most of us ache to belong somewhere? Part of what I wanted to explore in this book is how this desire makes us all capable of being complicit, of preserving the status quo as long as possible, especially when our little measures of short-term comfort and happiness are at stake.

History of Wolves delves into the power of perception, the power of faith, and the power--or powerlessness--of hindsight within a complex and tense narrative. What inspired the idea for History of Wolves?

I've always been intrigued by the way perception shapes the stories we tell and the realities we act upon. In History of Wolves, I grew interested in setting the story of Linda's history teacher, Mr. Grierson, next to the story of the Gardner family in order to think through the relationship of thought to action, and witness to responsibility. What seems to "count"--what we see, what we do, or what we think--shifts in different contexts, and I wanted to think through the complex and sometimes contradictory ways we hold people responsible for these various levels of involvement in events as they unfold. I have also always been fascinated by the way time affects stories as they are told. History of Wolves is a coming-of-age story told in retrospect: the first half of the book is a little closer to Linda as a teenager, while the second section pans out more, aligning the reader more closely with Linda as an adult. Through this structure, I hoped that the reader might experience something of the way hindsight reorders and reinterprets what we see, changing how events add up and ultimately what they mean.

How does it feel to have such strong support for your debut from independent booksellers? What can indie booksellers expect from you next?

It's very humbling and moving, especially because I know what a labor of love sustaining an independent bookstore is. It means so much to me to have the support of people who have devoted their lives to books, to finding ways of spreading stories and ideas in the world! It's such important work. As for the next project, I am now revising a collection of stories called Catapult that will be coming out with Sarabande in October of 2017. And there is perhaps another novel idea waiting for my attention when those revisions are complete, but it's still pretty embryonic. --by Sydney Jarrard

Emily Fridlund on History of Wolves, January's #1 Indie Next List Pick

Family is a murky theme in History of Wolves, and Linda exhibits an urgent sense of needing to belong. When she becomes the governess for the Gardner family, she nearly achieves that, but she's still stuck on the periphery. Why is the feeling of belonging so important to Linda?

Family is a murky theme in History of Wolves, and Linda exhibits an urgent sense of needing to belong. When she becomes the governess for the Gardner family, she nearly achieves that, but she's still stuck on the periphery. Why is the feeling of belonging so important to Linda?