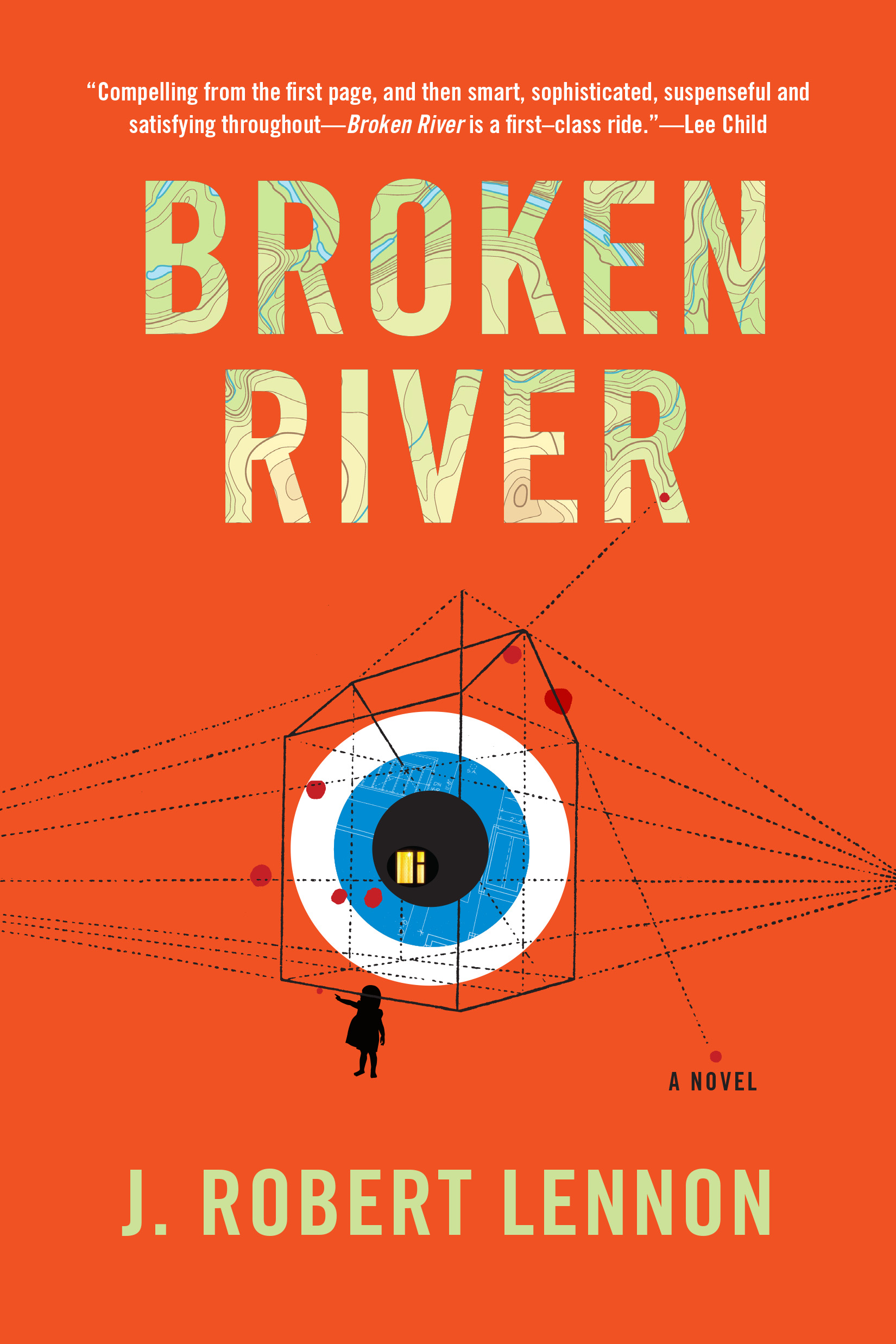

Broken River by J. Robert Lennon (Graywolf Press, trade paper, May 16) is the number-one Indie Next List pick for May as chosen by independent booksellers nationwide.

Broken River by J. Robert Lennon (Graywolf Press, trade paper, May 16) is the number-one Indie Next List pick for May as chosen by independent booksellers nationwide.

In this intense, literary thriller, a dissolving family--Karl, Eleanor, and their daughter, Irina--moves into a long-vacant house where many years prior a brutal murder occurred. As Karl and Eleanor drift further apart and young Irina grows convinced that a new girl in town is connected to the crime, the mysterious Observer watches over the characters and their interconnected storylines.

"Lennon's ability to invent and inhabit the inner worlds of men, women, children, and unexplained phenomena with equal nuance makes the novel's multiple perspectives shift and blend seamlessly," said Annie Metcalf of Magers & Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis, Minnesota. "Undeniably bizarre in its plot, yet unsettlingly real in its exploration of marriage, childhood, and regret, Broken River is classic indie bookstore fare: unafraid to blend genres, play with form, and surprise readers."

Lennon, who teaches writing at Cornell University, is the author of eight novels, including Familiar, Castle, and Mailman, and two story collections. His fiction has appeared in the Paris Review, Granta, Harper's, Playboy, and the New Yorker. Here, he discusses his latest work.

Broken River is unsettlingly dark and twisted. What was the inspiration behind it? Was this narrative arc your initial plan, or did elements of the story change as you wrote?

I had the idea to write an omniscient description of time passing in an unoccupied house, inspired by the middle chapter of [Virginia Woolf's] To the Lighthouse. That's the first chapter. I wrote it more or less off the top of my head, with no idea where it was going. The killings just sort of happened, and then I remembered a couple of criminals, Louis and Joe, from a failed novel I wrote years ago--the only thing in that book that I really liked. I decided they'd committed the crimes. Then I decided to have some people from the city buy the house, and I had to figure out who they were. The first draft was a wreck, but it had potential, I thought. In any event, it all grew out of that house description.

Why did you write sections of the book from the perspective of the Observer rather than a traditional narrator? Why take that slight step back from reality?

Well, the first chapter contains some pretty brutal murders that I wasn't eager to describe in detail. And I had decided to leave the point of view inside the house; that was a "rule" of the chapter. So, this served as just the distancing device I needed. Initially it was just a rhetorical experiment; I conjured up this notion of an observer, somebody who might be standing at the window. But by the end of the chapter, the Observer, capital O, seemed to be something else. I realized that it could have an arc, could be an entity that stood in for the reader, or the writer, or the part of us that generates and consumes narratives. In later drafts, I shaped and refined that arc, with the help of my editor, Ethan Nosowsky. The Observer is a ghost, in the sense that a ghost is an entity that watches and judges, and that might reveal itself to us at moments of intensified perception. It's a kind of glue made of consciousness.

Every member of the family--Karl, Eleanor, and Irina--is hiding something from the rest. Why create a family of liars?

Every member of the family--Karl, Eleanor, and Irina--is hiding something from the rest. Why create a family of liars?

Is there another kind of family?

As the father of boys, how did you approach writing the character of 12-year-old Irina? How did you anticipate how a young, quirky girl such as herself would think and act?

Irina's something of an idealized precocious child; I'm not sure how well-drawn a character she is, if the yardstick is pure psychological realism. But, honestly, it shouldn't be terribly hard for competent writers to convincingly render characters who reside elsewhere on the gender spectrum from their own experience. I've been a child, I've known women, and my sons' mother and I didn't raise them to inhabit traditional gender roles. It isn't, I don't think, rocket science. I do think this kind of creative challenge becomes knottier when you try writing outside your race and class comfort zones, at least in 2017; but I feel fairly capable of writing about an adolescent girl. I hope she's persuasive, anyway.

After moving upstate with her family, Irina misses her home in New York City and pines for her favorite bookstore, WORD. Are you an avid indie bookstore fan?

Talk about a softball question! Yes, of course--I adore my own local indie, Buffalo Street Books, and love reading at indie stores on tour. And I couldn't resist the shout-out to WORD, which has always treated me particularly well. The Broken River tour is going to be kind of a greatest-hits compilation of all my favorite places to read--I'm really looking forward to it. And I don't think I'd have a career at all without booksellers who cared about the kind of thing I write. I'm very grateful to them.

Between your writing, teaching, playing music, and Lunch Box podcast, you live quite a creative lifestyle. Where does all of that energy come from? How do these very different types of outlets mesh with your ideas?

Boy, I don't know. Anxiety, maybe? Teaching and music are performative outlets; there's an excitement to being exposed like that, having to come up with stuff to say and do on the fly, and enjoying people's reactions when it goes well. Writing's performative, too--I feel as though I'm putting on a little show for myself when I do it--but it has the obvious advantage of being editable. Ultimately, I think of writing as the perfect refinement of extemporaneous creation; it embodies, for me, the ideal balance between inspiration and productive tedium. As for podcasting, I've only got the one, and it's mostly a vessel for my friendship with Ed Skoog, which is a thing I treasure. --Sydney Jarrard for Indie Next List

J. Robert Lennon on Broken River, May's #1 Indie Next List Pick

Broken River by J. Robert Lennon (Graywolf Press, trade paper, May 16) is the number-one Indie Next List pick for May as chosen by independent booksellers nationwide.

Broken River by J. Robert Lennon (Graywolf Press, trade paper, May 16) is the number-one Indie Next List pick for May as chosen by independent booksellers nationwide. Every member of the family--Karl, Eleanor, and Irina--is hiding something from the rest. Why create a family of liars?

Every member of the family--Karl, Eleanor, and Irina--is hiding something from the rest. Why create a family of liars?