Chris Hedges, who lives in a house that holds 5,000 books and no television, is the author of nine books, including Empire of Illusion, The Death of the Liberal Class, American Fascists and War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. He was a New York Times foreign correspondent for 15 years and was part of a team of reporters who won the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for their work on global terrorism.

Chris Hedges, who lives in a house that holds 5,000 books and no television, is the author of nine books, including Empire of Illusion, The Death of the Liberal Class, American Fascists and War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. He was a New York Times foreign correspondent for 15 years and was part of a team of reporters who won the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for their work on global terrorism.

Joe Sacco studied journalism but only began to practice the profession properly when he married it with comics, his other love. He has written graphic books about the Palestinian Territories and Bosnia. A collection of his shorter pieces, Journalism, will also be published in June 2012.

Joe Sacco studied journalism but only began to practice the profession properly when he married it with comics, his other love. He has written graphic books about the Palestinian Territories and Bosnia. A collection of his shorter pieces, Journalism, will also be published in June 2012.

Together, they have written Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt (just out from Nation Books), which documents the lives of those who live in "sacrifice zones"--parts of the U.S. where corporate greed has run wild, and the locals have suffered.

On your nightstand now:

Chris Hedges: Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow by Leon F. Litwack. This is a book I am teaching to inmates in an African-American history course at a New Jersey prison--history at its best, exhaustively researched, shattering in its conclusions and beautifully written. He is one of our greatest historians. Castle to Castle by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, whose political views are repugnant, but who is one of the most original and talented satirical writers of the 20th century. The darkness of his humor appeals to the old war correspondent in me. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown--I am reading this book for a second time. It is a masterpiece, moving beyond words and flawlessly written. Brown exposes the dark heart of empire, the violent campaign of extermination unleashed against those whose lands we stole and the lies we told to others and tell to ourselves.

Joe Sacco: Foundations in the Dust by Seton Lloyd. My next project is chiefly about Mesopotamia, and this book tells the history of the archeologists who excavated the most well-known sites. As you can expect, it's full of colorful individuals dashing about, avoiding brigands, and sending treasures back to European museums.

Favorite book when you were a child:

CH: I loved the usual fare of children's books, especially Curious George and E.B. White's gorgeous masterpieces Stuart Little and Charlotte's Web. Winnie-the-Pooh was high on the list. And A.A. Milne, like E.B. White, was a great comic writer. I owned and read the complete collection of The Hardy Boys. I loved adventure stories, especially tales of explorations to the North Pole or down the Nile. The first "adult" book I read around the age of nine or 10 was called The Sea Devil--The Story of Count Felix Von Luckner, The German War Raider by Lowell Thomas. I went on to devour Bruce Catton's series on the Civil War. I was an early fan of John Steinbeck and remember getting choked up at about the age of 11 at the end of The Pearl. By the time I was a teenager, I wanted to be William Faulkner and wrote many awful short stories in an attempt to emulate him.

JS: I liked books on dinosaurs. I can't remember any of the titles I read because mostly I'd stare at the pictures. Perhaps my childhood claim to reading fame is that at age 10 I picked up a prose version of The Iliad, opened it to a page that mentioned something about an eyeball dangling on the tip of a spear, and then read the entire book hoping for more such goodies.

Your top five authors:

Your top five authors:

CH: William Shakespeare, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, Fyodor Dostoevsky and William Faulkner.

JS: In no particular order: George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, Ferdinand Celine, George Gissing and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Book you've faked reading:

CH: As an undergraduate and graduate student there were a few books that were skimmed rather than read. I had to read rather turgid works by theologians in divinity school such as Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher, so maybe I can be forgiven. I don't remember fooling any of my professors. But out in the real world, where I don't usually have books forced upon me, I am not shy about admitting the many holes in my reading.

JS: I came rather close to finishing War and Peace by Tolstoy--had a couple of hundred pages to go before I had to abandon the tome on my way overseas. But if the subject of Tolstoy ever comes up, I claim to have read the book, which is only nine-tenths true, and probably makes me a bit of a fraud.

Book you're an evangelist for:

CH: Life and Fate by Vasily Grossman, one of the greatest novels about life, war, love and meaning of the 20th century. Better, in my mind, than War and Peace on which it was loosely modeled, although I know this is heresy.

JS: Adam Hochschild's King Leopold's Ghost. To me, Hochschild is a model historian. This book, about the appalling atrocities committed in the Belgian Congo during the Scramble for Africa, is perfectly balanced--not just meticulously researched but also a real page-turner. "I couldn't put it down," as they say.

Book you've bought for the cover:

CH: I have bought replicas of classic first editions from the First Edition Library such as The Great Gatsby and The Sound and the Fury because I loved the old covers and the original format.

JS: Biggles of 266 by Captain W.E. Johns. I saw this in a bin of books at a department store when I was a child and made my mother buy it for me based on the cover illustration. It showed First World War fighter planes engaged in a ferocious dogfight. One of the planes is engulfed in flames, and its pilot is leaning over the edge of the fuselage, looking back. Awful! But that book launched me into a lifelong fascination with the First World War.

Book that changed your life:

CH: Moral Man and Immoral Society by Reinhold Niebuhr. It gave me the language by which I could begin to describe human nature, good and evil and the moral life. I have read all of Niebuhr's books at least once and this book three times.

JS: The Road to Wigan Pier by George Orwell. Orwell's investigation of the working conditions in the middle of England during the Depression took him into the homes of coal miners and down into the pits. His engagement with his subject was a great inspiration to me. The lesson was: one had to go and see if one was going to have a hope of understanding.

Favorite line from a book:

CH: From Samuel Beckett's The Unnamable:

"I'll go on. You must say words, as long as there are any--until they find me, until they say me. (Strange pain, strange sin!) You must go on. Perhaps it's done already. Perhaps they have said me already. Perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story. (That would surprise me, if it opens.)

It will be I? It will be the silence, where I am? I don't know, I'll never know: in the silence you don't know.

You must go on.

I can't go on.

I'll go on."

JS: "Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two makes four." --from George Orwell's 1984.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

CH: In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust. I have read all six volumes twice. Shelby Foote read it nine times. He identified Proust, correctly, as "the Shakespeare of our time." I won't make it to that number, but I will certainly read it again. In Search of Lost Time, like all great works of literature, gives you words to describe aspects of human reality that before Proust were difficult and often impossible to articulate. Besides, I read it with Eunice, who became my wife, and it reminds me of falling in love.

JS: Brave New World by Aldous Huxley. I remember the thrill of reading this book, so crammed with interesting, weird, and wild ideas, when I was about 13. I was horrified by Huxley's vision, of course, but every few years I reenter his dystopian world to remind myself how prescient he was.

"The first modern celebration of Bloomsday was in 1954, the 50th anniversary of the fictional events in Joyce's book, and about three decades after Joyce published his novel in 1922. Irish writers Flann O'Brien and Patrick Kavanagh got together with critic John Ryan and a dentist cousin of James Joyce, named Tom Joyce, to make a daylong pilgrimage around Dublin. They were to have stops at the Martello Tower (the opening scene of the novel), Davy Byrne's Pub (where Bloom eats a gorgonzola cheese sandwich) and 7 Eccles Street (where Bloom and his wife, Molly, lived). They role-played, acted out the dialogue, and rode in horse-drawn carriages like those described in the scene of Paddy Dignam's funeral. They were supposed to end up in the red-light section of Dublin, where the 15th chapter of Ulysses 'Nighttown' is set, but the literary pilgrims got a bit drunk and distracted at a pub about halfway through the route and lost their ambition to finish it."

"The first modern celebration of Bloomsday was in 1954, the 50th anniversary of the fictional events in Joyce's book, and about three decades after Joyce published his novel in 1922. Irish writers Flann O'Brien and Patrick Kavanagh got together with critic John Ryan and a dentist cousin of James Joyce, named Tom Joyce, to make a daylong pilgrimage around Dublin. They were to have stops at the Martello Tower (the opening scene of the novel), Davy Byrne's Pub (where Bloom eats a gorgonzola cheese sandwich) and 7 Eccles Street (where Bloom and his wife, Molly, lived). They role-played, acted out the dialogue, and rode in horse-drawn carriages like those described in the scene of Paddy Dignam's funeral. They were supposed to end up in the red-light section of Dublin, where the 15th chapter of Ulysses 'Nighttown' is set, but the literary pilgrims got a bit drunk and distracted at a pub about halfway through the route and lost their ambition to finish it."

Yesterday in comments to the Department of Justice, the American Booksellers Assocation called the Agency Model "a perfectly legitimate mode of business" and said the organization is

Yesterday in comments to the Department of Justice, the American Booksellers Assocation called the Agency Model "a perfectly legitimate mode of business" and said the organization is

U.S. State Department

U.S. State Department SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

On Wednesday night, Dark Delicacies: Books, Gifts and Collectibles in Burbank, Calif., held a dress-up contest for an appearance by Vicki Pettersson, author of The Taken (Harper Voyager). Here Pettersson (r.) poses with the winner, who received a store gift card.

On Wednesday night, Dark Delicacies: Books, Gifts and Collectibles in Burbank, Calif., held a dress-up contest for an appearance by Vicki Pettersson, author of The Taken (Harper Voyager). Here Pettersson (r.) poses with the winner, who received a store gift card.  Congratulations to

Congratulations to  Toronto's

Toronto's  Sugarhouse: Turning the Neighborhood Crack House into Our Home Sweet Home

Sugarhouse: Turning the Neighborhood Crack House into Our Home Sweet Home

Chris Hedges, who lives in a house that holds 5,000 books and no television, is the author of nine books, including Empire of Illusion, The Death of the Liberal Class, American Fascists and War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. He was a New York Times foreign correspondent for 15 years and was part of a team of reporters who won the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for their work on global terrorism.

Chris Hedges, who lives in a house that holds 5,000 books and no television, is the author of nine books, including Empire of Illusion, The Death of the Liberal Class, American Fascists and War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. He was a New York Times foreign correspondent for 15 years and was part of a team of reporters who won the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for their work on global terrorism. Joe Sacco studied journalism but only began to practice the profession properly when he married it with comics, his other love. He has written graphic books about the Palestinian Territories and Bosnia. A collection of his shorter pieces, Journalism, will also be published in June 2012.

Joe Sacco studied journalism but only began to practice the profession properly when he married it with comics, his other love. He has written graphic books about the Palestinian Territories and Bosnia. A collection of his shorter pieces, Journalism, will also be published in June 2012. Your top five authors:

Your top five authors: Santiago Gamboa's Necropolis is a hefty, Decameron-like opus, a story-within-story-within-story set in war-torn Jerusalem, told by an unnamed 40ish narrator who, like Gamboa, is a Colombian novelist living in Rome. Receiving a letter inviting him to the International Conference on Biography and Memory, with no idea why he's been invited, the narrator finds himself in a hotel full of eccentric delegates--all storytellers, spinning tales of chess, God and drug addiction.

Santiago Gamboa's Necropolis is a hefty, Decameron-like opus, a story-within-story-within-story set in war-torn Jerusalem, told by an unnamed 40ish narrator who, like Gamboa, is a Colombian novelist living in Rome. Receiving a letter inviting him to the International Conference on Biography and Memory, with no idea why he's been invited, the narrator finds himself in a hotel full of eccentric delegates--all storytellers, spinning tales of chess, God and drug addiction.

BEA in space: Heading up the West Side Highway from Javits on Wednesday, I realize the space shuttle Enterprise is supposed to "land" on the deck of the Intrepid Museum today. Is it there yet? I take out my camera. Seated on the right side of a moving bus, I know my only shot will be through the opposite window and across the highway. When the moment arrives, I snap two quick photos. Like many aspects of our business, it comes down to planning, reaction, adaptation and execution, plus a generous dose of blind luck.

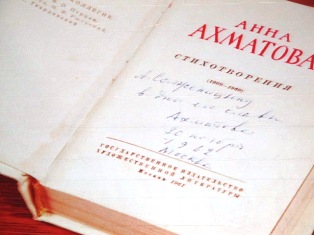

BEA in space: Heading up the West Side Highway from Javits on Wednesday, I realize the space shuttle Enterprise is supposed to "land" on the deck of the Intrepid Museum today. Is it there yet? I take out my camera. Seated on the right side of a moving bus, I know my only shot will be through the opposite window and across the highway. When the moment arrives, I snap two quick photos. Like many aspects of our business, it comes down to planning, reaction, adaptation and execution, plus a generous dose of blind luck.  My favorite book: BEA is all about finding great new titles, but one now forever imprinted upon my mind is the photo of a collection of Anna Akhmatova's poems, inscribed to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. It is part of the vast Solzhenitsyn Archive, which was the subject of an extraordinary slide show presentation at BEA by his widow, Natalia.

My favorite book: BEA is all about finding great new titles, but one now forever imprinted upon my mind is the photo of a collection of Anna Akhmatova's poems, inscribed to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. It is part of the vast Solzhenitsyn Archive, which was the subject of an extraordinary slide show presentation at BEA by his widow, Natalia.  BEA in space, part 2: On the final day, I stand by the Galleria windows, which afford a panoramic view of the BEA show floor. It's like being on the command deck of a spaceship, scanning the planet below for signs of intelligent life. You can see those signs everywhere you look, if you're paying attention.--

BEA in space, part 2: On the final day, I stand by the Galleria windows, which afford a panoramic view of the BEA show floor. It's like being on the command deck of a spaceship, scanning the planet below for signs of intelligent life. You can see those signs everywhere you look, if you're paying attention.--