|

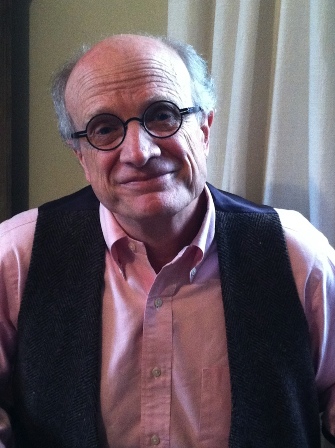

| photo: Leslie Dillen |

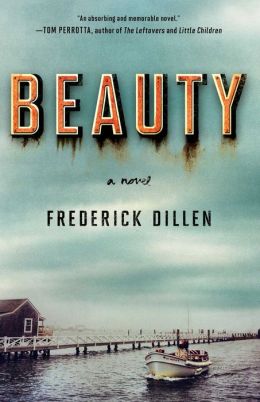

Frederick Dillen was born in Greenwich Village in New York City, raised on scholarship in a New Hampshire boarding school and graduated from Stanford. His short fiction has appeared in literary quarterlies and Prize Stories 1996: The O. Henry Awards. His book Hero was named Best First Novel of 1994 by the Dictionary of Literary Biography. His second novel, Fool, was a Nancy Pearl Book Lust Rediscovery. Dillen's newest novel is Beauty (Simon & Schuster, March 4, 2014). Dillen and his wife, Leslie, are parents of two grown daughters and live in New Mexico with a frantic, yellow, 50-pound, knee-high, one-ear-up-one-down shelter-dog named Lucy.

On your nightstand now:

Renata Adler's novel Speedboat, a New York Review of Books reissue (originally out in the mid-'70s). Adler is smart, and her smarts have range and depth and nuance. For how bright she is, she's not just accessible but is at moments all but unbearably vulnerable. There are these fine sentences, not pretentious but fine enough to keep you at an admiring distance, and then the bottom falls out and you are instantly inside anybody's--even your own--life split open. Speedboat arrives in a collage of impression and snippet, each arresting, many unconnected, all outside of, or very mixed up in, traditional sensibilities about time and story. The result being that if you're going to make it through Speedboat, you have to just let it wash over you. The what-happens-next of a story is hardly to be found, and yet, for me, the novel works wonderfully.

Off the point, the voice that comes to me in Speedboat is the voice of a girl a bit older than I once was, and a lot cooler. She knows things, and when she doesn't, they are the right things not to know. She has adventures and has them without a thought. She is bafflingly, heartbreakingly unreachable, except when she is.

Favorite book when you were a child:

I grew up in a family that had penetrating misfortunes, and I can remember baseball through that scrim, but not a favorite book. And although my parents were educated and kind and, in early days, functional, they didn't read to me. What I do remember is reading to my own daughter Abigail when she was little. I read her everything, from Pooh and Toad to Charlotte and the Wild Things and Eloise. But what I had most fun reading were the Joel Chandler Harris stories about Brer Rabbit and his gang. I knew the stories were politically incorrect by that time, and incorrect not least because of their dialect, but that dialect let me make voices, and Abbie liked the voices, and I liked making them. What can I say? Well, I can apologize. But nobody else heard, and those half hours at Abbie's naptime were a joy.

Your top five authors:

Flannery O'Connor, the stories especially. And then it's changeable, depending. I've been rereading Americans, so: Twain, especially in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; Bellow in Herzog; Roth in parts, if never the whole book, but the parts are so good who cares. And the crime novel addiction beginning, as ever, with Chandler and Hammett.

Book you've faked reading:

In maybe fourth grade at our public school, there was a weekly library hour, and one week it came to me I should be a reader, so I took out seven books--a couple of Freddy the Pigs, The Kid Who Batted 1.000, so on. Library day the next week, I got off the bus with my seven books to return, and a girl said accusingly, like she really knew, "You didn't read all those books." Although I wasn't happy about lying, I didn't give a thought to not lying. I said, sternly, defensively I guess--still a vivid memory, on the steps off the bus, not fun--I said, too loud, "Yes I did." She didn't believe me, but she walked away.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Andre Dubus, the father of the current memoirist and novelist by the same name, was one of the great American short-story writers. Other serious writers profoundly admired Andre's work, but he never received corresponding popular acclaim, and I worry that his stories are slipping below the radar of today's readers. His Selected Stories is a great, great book and an introduction to more great work.

Book you've bought for the cover:

If I see a lurid cover for a noir, say, The Maltese Falcon, I grab the book.

Book that changed your life:

It came late, after a good education and several years guessing that I wanted to write: Flannery O'Connor's Everything That Rises Must Converge. The weirdness, the black humor, the urgency of pain, the slipperiness of the ordinary and the gothic theological horrors reaching blind for redemption, and all of it through the luminous (not a comma wasted, never a careless word) subversion of O'Connor's prose. It came to me that this was why I had chosen writing instead of a usual job. Not that I write in O'Connor's vein or, please, imagine my work in the same room with hers, but the voice of her work is inside me, prodding me into something that might be godly terror.

Favorite line from a book:

A favorite line and a last line, The Great Gatsby, of course. It still works:

"So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

And a mystery bonus, to do with a police horse on the streets of New York during a potentially difficult encounter:

"But then the carrot was sniffed, and the lips flopped over it like a retired trumpet player at a martini, and half the carrot was gone." [Ed.: Mystery solved! This line comes from Dillen's own Fool.]

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Thurber has a story called "The Dog That Bit People." I loved the story, thought it immensely funny, could barely finish it for laughing when I read it aloud to my girls, who also laughed--though whether at me or the story, I couldn't be sure. When my godmother, Caroline, whom I loved with every bone in my body, was dying, I took "The Dog That Bit People" to read to her and cheer her up. She saw me and knew me, but little else; there was little of her left. I started to read the story and wept into the pages and couldn't go on. I have not looked at the story since, but there is a part of me that wants to think if I did read it again, and if I laughed until I couldn't breathe, and if my girls were girls again and laughed too, then Caroline would be fine and would laugh with us.

The Books-A-Million store at Parkdale Mall in Beaumont, Tex., closed last Saturday, but will re-open in May as the chain's first 2nd and Charles location in the state, the Beaumont Enterprise reported, noting that "the words, 'A new experience in reading, watching, playing and grooving is coming very soon,' and the black plastic covering the windows and doors were not a good sign to those who cling to a passion for printed books." While local employees said the store will open in May, 2nd and Charles spokeswoman Christine Corbitt could not confirm the date.

The Books-A-Million store at Parkdale Mall in Beaumont, Tex., closed last Saturday, but will re-open in May as the chain's first 2nd and Charles location in the state, the Beaumont Enterprise reported, noting that "the words, 'A new experience in reading, watching, playing and grooving is coming very soon,' and the black plastic covering the windows and doors were not a good sign to those who cling to a passion for printed books." While local employees said the store will open in May, 2nd and Charles spokeswoman Christine Corbitt could not confirm the date.

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.S1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

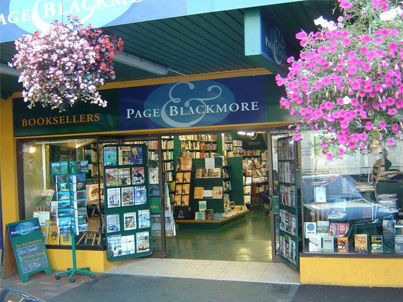

Page & Blackmore was founded by Susi & Tim Blackmore and Peter & Ann Rigg in 1998. Each couple had been operating a bookstore on Trafalgar Street, and the creation of Page & Blackmore was conceived as a merger that would put the owners of both Blackmore's Booksellers and Pages Bookshop in a stronger position.

Page & Blackmore was founded by Susi & Tim Blackmore and Peter & Ann Rigg in 1998. Each couple had been operating a bookstore on Trafalgar Street, and the creation of Page & Blackmore was conceived as a merger that would put the owners of both Blackmore's Booksellers and Pages Bookshop in a stronger position. The

The  Yesterday comedienne/actress/writer Annabelle Gurwitch appeared on CBS This Morning to discuss her new book, I See You Made an Effort: Compliments, Indignities, and Survival Stories from the Edge of 50 (Blue Rider). Here she is in the green room pre-show with Naomi Campbell, who also guested.

Yesterday comedienne/actress/writer Annabelle Gurwitch appeared on CBS This Morning to discuss her new book, I See You Made an Effort: Compliments, Indignities, and Survival Stories from the Edge of 50 (Blue Rider). Here she is in the green room pre-show with Naomi Campbell, who also guested.

"Over time, Watermark Books has become more than a bookstore to me, and perhaps, ultimately, that's what makes it home. If it were a storyteller, it'd be able to write its share of my own life story. I've played Scrabble there. Gone on dates. Later sat plotting revenge against said dates. Skipped school. Cried to my best friend. Tried fighting the good fight, be it organizing students for Darfur or fighting injustice in the local ballet world. Sat on a bench outside the bookstore, reading The Bell Jar, simultaneously hating/loving the book for brushing up against my own teenage angst. Tried writing novels. Failed writing novels. Dreamed of the day I might return to Watermark Books for my own book launch party. And that thought is often what keeps me going, draft after draft."

"Over time, Watermark Books has become more than a bookstore to me, and perhaps, ultimately, that's what makes it home. If it were a storyteller, it'd be able to write its share of my own life story. I've played Scrabble there. Gone on dates. Later sat plotting revenge against said dates. Skipped school. Cried to my best friend. Tried fighting the good fight, be it organizing students for Darfur or fighting injustice in the local ballet world. Sat on a bench outside the bookstore, reading The Bell Jar, simultaneously hating/loving the book for brushing up against my own teenage angst. Tried writing novels. Failed writing novels. Dreamed of the day I might return to Watermark Books for my own book launch party. And that thought is often what keeps me going, draft after draft." The GBO said that Goose the Bear "tells the heartwarming and species-confused story with the help of colorful, offbeat illustrations and narrative by writer and illustrator Katja Gehrmann."

The GBO said that Goose the Bear "tells the heartwarming and species-confused story with the help of colorful, offbeat illustrations and narrative by writer and illustrator Katja Gehrmann." Savage Harvest: A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller's Tragic Quest for Primitive Art

Savage Harvest: A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller's Tragic Quest for Primitive Art The great thing about this award, the great thing about literature in translation in general, is that the books won't find their way to the end of an algorithm and several wouldn't work at all as e-books. (For example, in Her Not All Her, 11 sentences in the original German are written between the lines in a different color--red--and full-bleed color illustrations facing the text. Leg over Leg has the original Arabic on the facing pages. A True Novel is a two-volume slipcase. You could read it on a device but that just wouldn't be any fun.) And they, of course, all look really nice next to each other. These books are made for handselling. You'll soon be able to

The great thing about this award, the great thing about literature in translation in general, is that the books won't find their way to the end of an algorithm and several wouldn't work at all as e-books. (For example, in Her Not All Her, 11 sentences in the original German are written between the lines in a different color--red--and full-bleed color illustrations facing the text. Leg over Leg has the original Arabic on the facing pages. A True Novel is a two-volume slipcase. You could read it on a device but that just wouldn't be any fun.) And they, of course, all look really nice next to each other. These books are made for handselling. You'll soon be able to

Book you're an evangelist for:

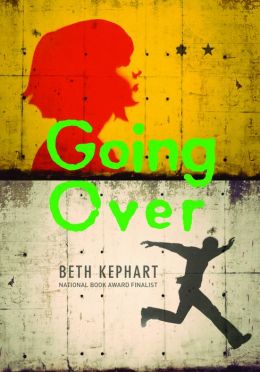

Book you're an evangelist for: Going Over, the newest novel from Beth Kephart, like her

Going Over, the newest novel from Beth Kephart, like her