|

| photo: Isabelle Selby |

Anthony Doerr is the author of the story collections Memory Wall and The Shell Collector, the novel About Grace, and the memoir Four Seasons in Rome. He has won numerous prizes both in the U.S. and abroad, including four O. Henry Prizes, three Pushcart Prizes, the Rome Prize, the New York Public Library's Young Lions Award, the National Magazine Award for fiction, a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Story Prize. Doerr lives in Boise, Idaho, with his wife and two sons.

Writing this book took 10 years. You must have done extensive research on World War II and its aftermath. And then there was the matter of absorbing everything (or so it seems) about electronics, puzzle boxes, gemstones, blindness, snails, post-traumatic stress and one of the novel's most haunting leitmotifs--birds. But all this learning emerges naturally in the course of the novel. Did you have to let your researches go at a certain point?

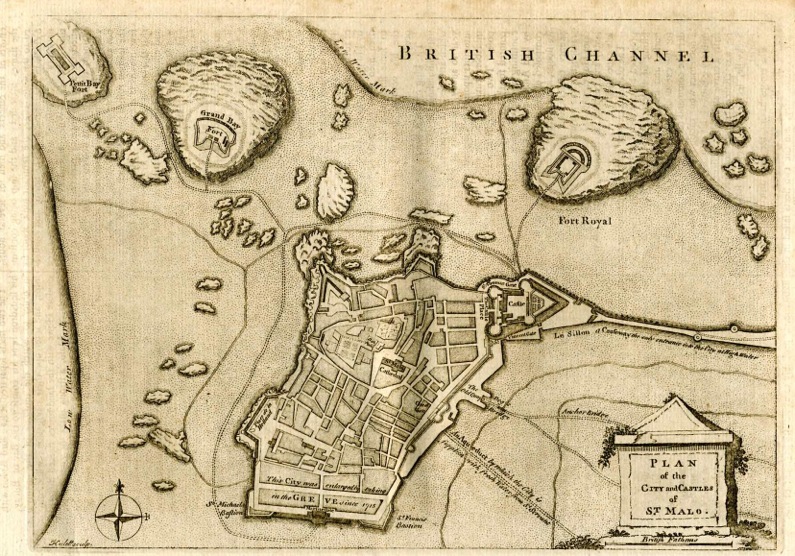

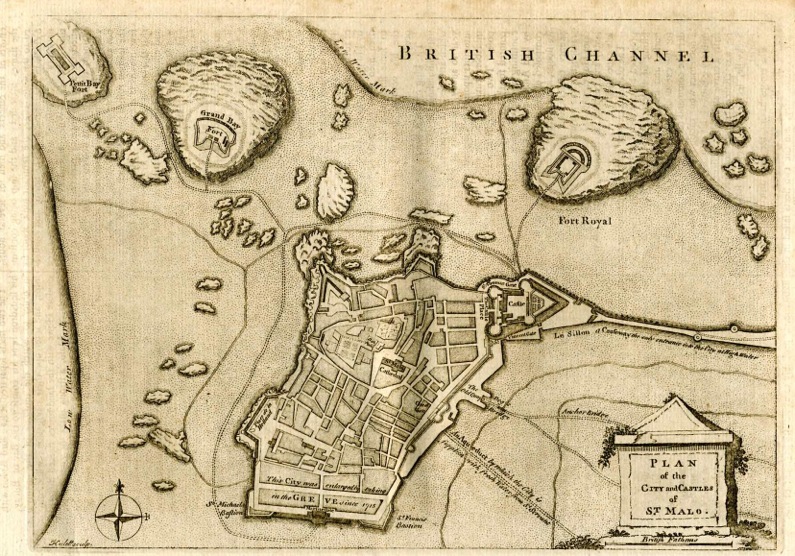

I was so afraid of telling a clichéd World War II story, so there were months where I was very anxious and would write short stories in between because I felt like this thing was too big. I mean, there are no American characters in the novel and I had never set anything this far in the past where, if you had a character go to her dresser, it was not immediately available to me what was on her dresser in 1936 or 1944. So, yes, having to go back and look at so many photographs, asking was there a refrigerator, was there a school for the blind in Paris, how would Marie-Laure's father have gotten out of the draft, how did keys work at the National Museum of Natural History--all these things would lead me to fun wormholes of research, but they would often provide procrastination where my fear was keeping me from writing, so instead I would just go read. There are so many books about the war that you could cover Germany with them to a depth of two feet!

Also, the structure is so complicated--there are 300-some chapters--I would lay them with index cards--on the floor, the walls, color-coded--to try to understand the story. To bring Marie-Laure and Werner forward in time, to see if more was happening in Werner's life than Marie-Laure's. I was wedded to this A-B-A-B symmetry that I'm not sure I always needed; I had to give myself a lot of permission to occasionally break that pattern. So it was a lot of puzzling through the structure.

Also, the structure is so complicated--there are 300-some chapters--I would lay them with index cards--on the floor, the walls, color-coded--to try to understand the story. To bring Marie-Laure and Werner forward in time, to see if more was happening in Werner's life than Marie-Laure's. I was wedded to this A-B-A-B symmetry that I'm not sure I always needed; I had to give myself a lot of permission to occasionally break that pattern. So it was a lot of puzzling through the structure.

Andrea Barrett has always been a model for me. She once told me to imagine that in a historical novel you're making your reader a cup of tea. When you research, sometimes you fall in the love with the astonishing facts--the tea leaves, if you will--and you want to present those to your reader and say, "Look how amazing this tea leaf is!" Eventually, you have to let everything steep for a while, strain out all the leaves, and give your reader a nice hot cup of tea!

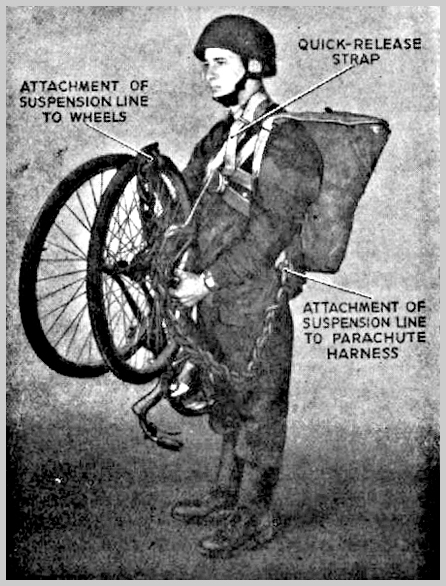

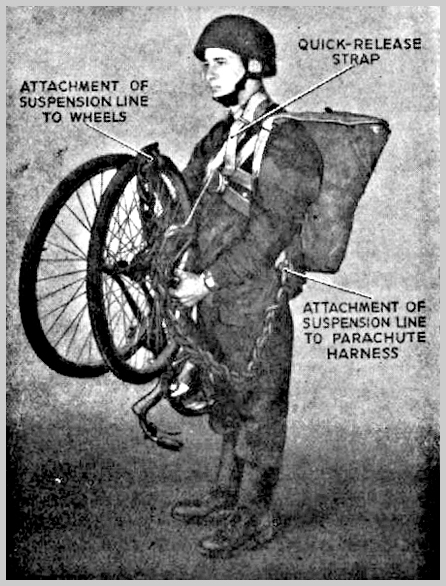

Early on I struggled so much with amazing pieces of information. Did you know that Canadian paratroopers had fold-up bicycles that they jumped with, then unfolded and rode off on? You fall in love with something like that, you spend days writing that scene, then you realize it has nothing to do with the story. But even though those days of following that lead were in a sense wasted, you have hopefully learned something that infuses your writing with truth--the nice hot cup of tea.

Early on I struggled so much with amazing pieces of information. Did you know that Canadian paratroopers had fold-up bicycles that they jumped with, then unfolded and rode off on? You fall in love with something like that, you spend days writing that scene, then you realize it has nothing to do with the story. But even though those days of following that lead were in a sense wasted, you have hopefully learned something that infuses your writing with truth--the nice hot cup of tea.

I'm curious about so many things, and procrastination can be a problem. But part of maturity as a writer is giving things up.

Increasingly in your fiction and in your memoir of your year in Rome (Four Seasons in Rome), you've come to write in the historic present. Can you discuss the gifts that this mode allows you? Are there any cons?

I do write in the present tense. I like all the "esses" it provides, the sound of the sentences, the music of it. Another fear I have is that when I'm in the past, which is most of the book, I'm still in the present tense--I wonder if the reader will be confused; still, it felt too flashback-y to use the past tense. But mostly it's because I like the literal sound of the present.

Where and when did your gifted and burdened heroine and hero, Marie-Laure and Werner, first come to you?

Where and when did your gifted and burdened heroine and hero, Marie-Laure and Werner, first come to you?

I always try to dispel for my students the notion that characters appear like cartoon light bulbs over one's head. But there was a moment, in New York in 2004, on the subway. I heard a man angrily complain about the coverage on his cell phone. I was trying not to judge him but I was thinking what a miracle a cell phone is. So that night I started writing about a girl transmitting a Jules Verne story to a boy who is trapped in a hole. I was intrigued with the idea that radio waves carry light, carry imagination that pass through walls and over great distances. So I had a girl who was interested in books and a boy who was trapped.

An intriguing theme is the radio and the connection it provides--it's a wondrous lifeline for Marie-Laure; for Werner it's first his salvation, then his undoing, finally a means for redemption. It's his "higher magic."

I really wanted to conjure a time when hearing the voice of a stranger in your house was a miracle, and so powerful. The mystery of humans hearing people this way, when previously you had to see the person you heard.

The idea of recording, too--that's what books do for me, the idea that you can read the words of Anne Frank, and in those sentences she lives. All these voices waiting to be heard. This is a lifelong interest of mine: memory and how we defy erasure by writing and recording. It's a way of at least temporarily sidestepping mortality.

One of the passages that stood out was about bravery. Marie-Laure says it is to live her life; Werner says, "Today maybe I did," when previously Werner told himself there were no choices.

That's the whole project of the book. I think it's too simple to suggest that all the Germans were evil and all the Americans were heroes. I worry that every day we lose more people for whom the war is memory, something of history--we watch these ridiculous things on the History Channel that are animated, so simplified. It's complicated.

.jpeg) My favorite character, Frederick, has a small but significant moment of bravery.

My favorite character, Frederick, has a small but significant moment of bravery.

He's a lot like my son Owen, to the point where my wife had a hard time reading about him. It's so tricky to make a Hitler Youth sympathetic, but amongst every hundred thugs, there had to be a sweet dreamer like Frederick and his birds. That really ties into your earlier question about Werner's choices. Is evil a weird sub-strain mutant thing in us? I tend to side with somebody like Solzhenitsyn who said something to the effect that it's a series of small steps that lead to some behaving evilly, and the amount of generosity in that statement, where he attempts to empathize with his torturers, is amazing. I feel like I would not have been strong enough to hide an entire Jewish family in my basement in 1940 in Berlin.

You have a fear of cliché--but snails, an unexpected thread throughout the novel, are certainly not a cliché. You give Marie-Laure something so concrete and tactile with the snails in the grotto and the shells she learns about in the museum and at her Uncle Etienne's.

I grew up in Ohio, and over spring break we'd go to Florida, we'd drive 24 hours, leaving the snow, to Sanibel Island--shell heaven. At low tide, we'd walk around and collect things. I loved it. The first book I ever wrote was a handbook about mollusks, in a little purple journal my mom gave me--these little creatures made these houses that were so lovely.

I rediscovered that passion when I went back to my parents' in my 20s, and found shells I had collected as a boy--the feel of the cowries with their exquisite polish, the murex like its own little kingdom... it reinforced the idea that a visually impaired person would have very tactile impressions.

In one passage you describe peaches as wedges of wet sunlight. Your images are so sensual. Is that intentional, to mimic what Marie-Laure can remember and imagine?

Very intentional. It's the way I write--I am a very visual writer, and taking on a blind protagonist was a way for me to address some of my weaknesses and live more in a world of texture and smell. There were times in the midst of the book when I was writing where I'd come up out of it and forget I could see for a few minutes. I managed to at least partially imagine what it's like to have that sort of limitation. In some ways maybe I romanticize it and make her capable of too much, but I try to remind the reader occasionally that she is a disabled person. And she was an easier character for me--all her motivations are purer--she's doing the right thing most all the time.

You write in your acknowledgments that you owe a debt to Jacques Lusseyran's memoir And There Was Light.

It's beautiful, it's quite well-written. He lost his sight at a young age, like Marie-Laure. What's beautiful about it is that his parents didn't see it as a disability; he never gave in to despair. He led a busy boyish life, and he became convinced, in an almost mystical way, that the world is composed of light and that he figured out some ways to actually see it. He becomes involved in the French Resistance because he is so good at listening to voices that people think he is like a lie detector. It helped me a lot in unlocking Marie-Laure, and the way that parents can help children through this, can train them and get them ready for the world.

Let's talk about sympathy for villains: Sergeant Major Reinhold von Rumpel, for instance.

Do you feel any sympathy for von Rumpel?

No.

Do you feel any for Volkheimer?

Yes.

Good... he's likable, but he's also a murderer. I fought with my editor about the final section with him where he gets the letter. I was trying to show how he was both ruined and trying to redeem himself. But von Rumpel was easy to write, and I worry that he's too purely an antagonist. He's my gesture toward the accepted Nazi character that readers are used to seeing. But I use him put pressure on the narrative--he's a ticking clock. I'm trying to attempt to say in the book with Volkheimer and Werner that evil is not something that is inevitable or complete in all of us.

Through the nationalism hammered into the children through the radio, the circumstances they were born into--they were trapped, and maybe you make choices that step by step take you toward evil. The school Werner and Volkheimer were in was Lord of the Flies mixed with Goethe, science and phrenology.

Would you agree that this is very much a novel about the power of literature, learning and resolve? These save Marie-Laure and Werner but also at times endanger them.

A lot of it is unconscious, but certainly the Jules Verne (that she reads in Braille) is conscious--this idea that by occupying stories throughout her life, Marie-Laure can both escape and live in two separate places. That's something that I feel so deeply. I am only happy when I am reading a novel that I like and that I'm writing something I like and that I'm doing something in the world. Being in those three spaces all at once--that's how I have found to live a meaningful life. --Marilyn Dahl

Early on I struggled so much with amazing pieces of information. Did you know that Canadian paratroopers had fold-up bicycles that they jumped with, then unfolded and rode off on? You fall in love with something like that, you spend days writing that scene, then you realize it has nothing to do with the story. But even though those days of following that lead were in a sense wasted, you have hopefully learned something that infuses your writing with truth--the nice hot cup of tea.

Early on I struggled so much with amazing pieces of information. Did you know that Canadian paratroopers had fold-up bicycles that they jumped with, then unfolded and rode off on? You fall in love with something like that, you spend days writing that scene, then you realize it has nothing to do with the story. But even though those days of following that lead were in a sense wasted, you have hopefully learned something that infuses your writing with truth--the nice hot cup of tea. Where and when did your gifted and burdened heroine and hero, Marie-Laure and Werner, first come to you?

Where and when did your gifted and burdened heroine and hero, Marie-Laure and Werner, first come to you?.jpeg) My favorite character, Frederick, has a small but significant moment of bravery.

My favorite character, Frederick, has a small but significant moment of bravery.