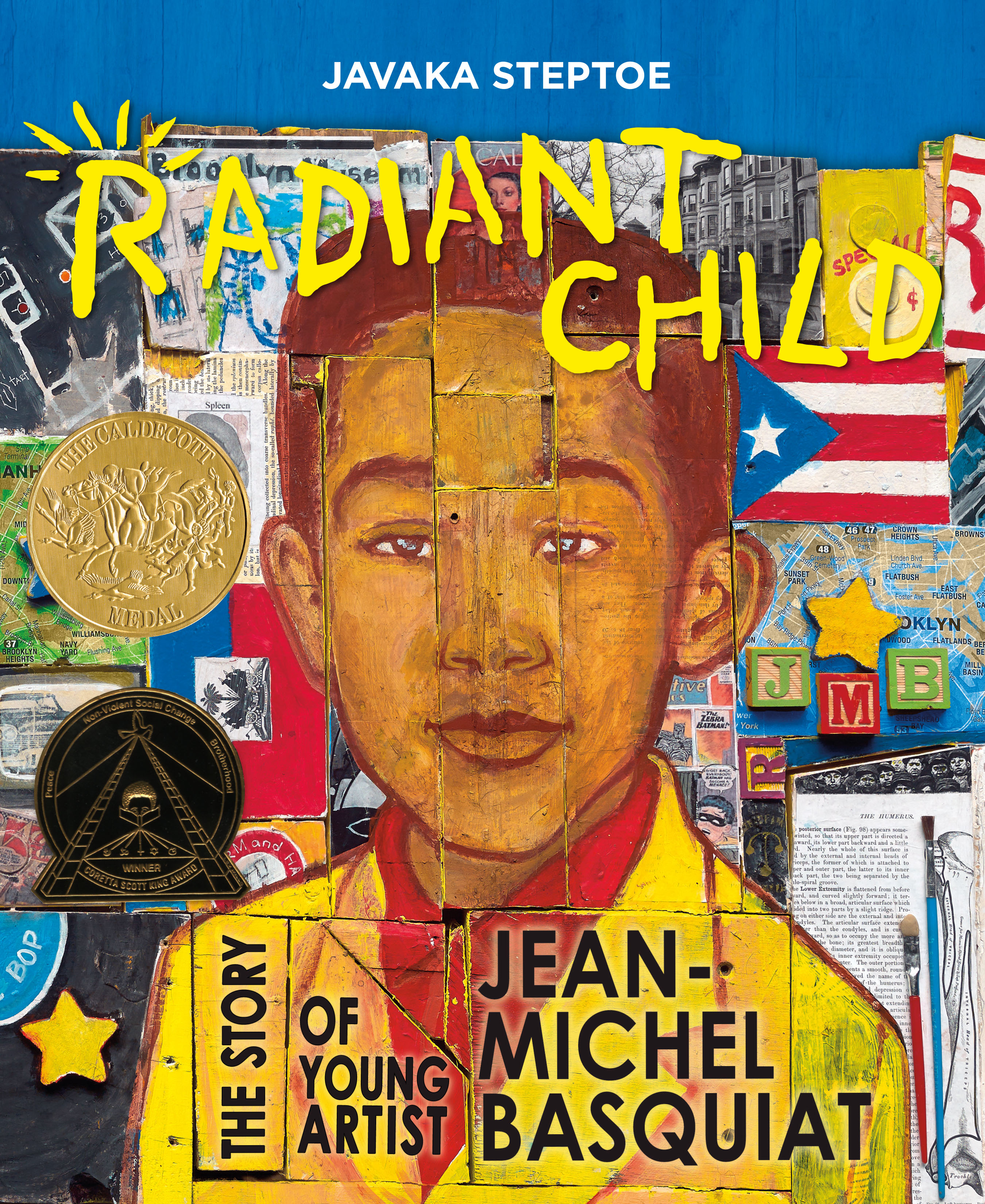

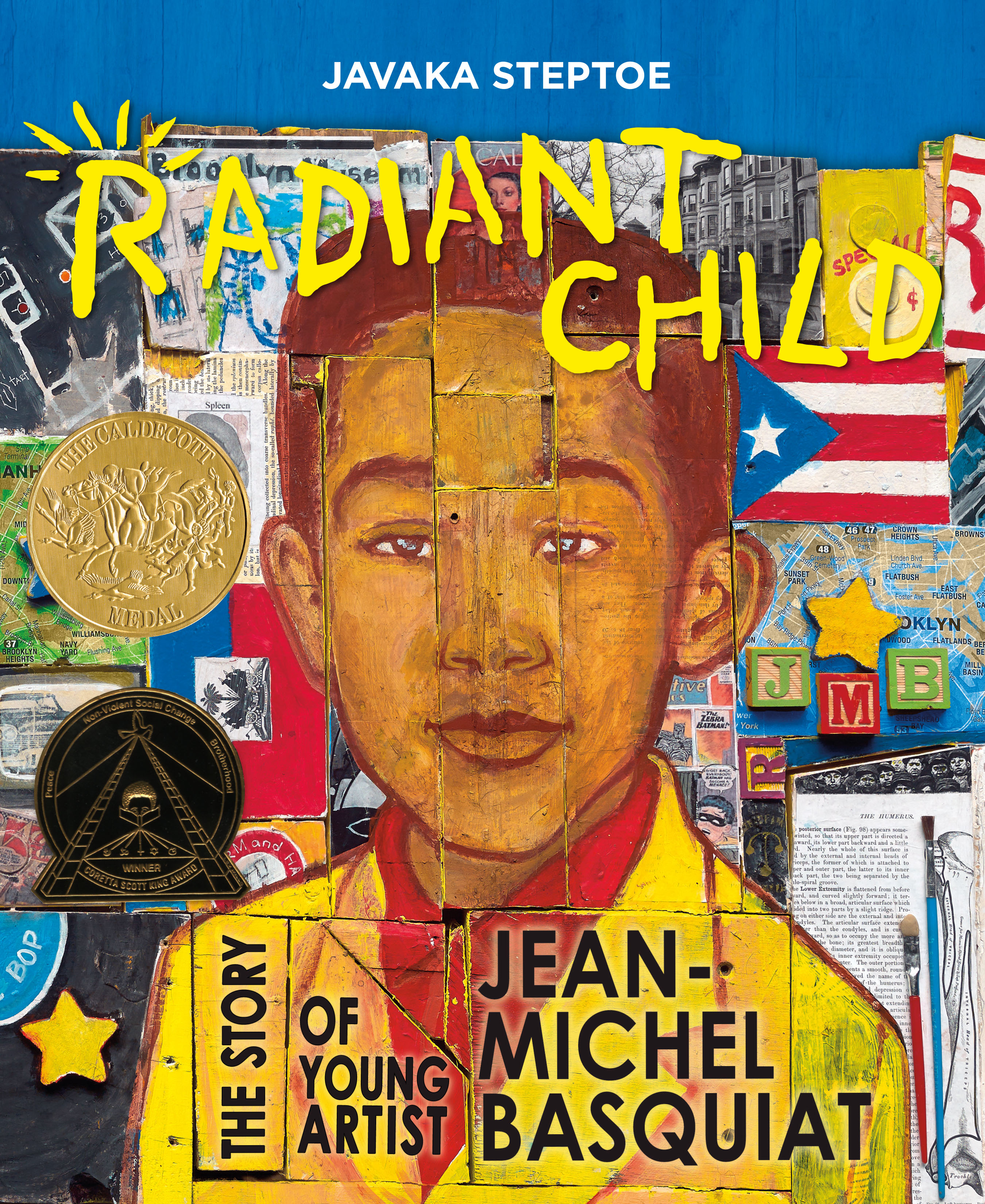

"Somewhere in Brooklyn, between the hearts

that thump, double Dutch, and hopscotch

and salty mouths that slurp sweet ice,

a little boy dreams of being a famous ARTIST." --from Radiant Child

_Gregg_Richards_012517.jpg) |

| photo: Gregg Richards |

Javaka Steptoe is an award-winning artist, author, designer and illustrator. His debut picture book, In Daddy's Arms I Am Tall, won the Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award in 1998, and Jimi: Sounds Like a Rainbow by Gary Golio received a Coretta Scott King Honor. His latest book, Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers), won the 2017 Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award and the 2017 Caldecott Medal. Shelf Awareness talked with Steptoe on the phone, hours after these awards were announced in Atlanta on January 23.

Congratulations, Javaka! Everybody wants to hear about "the call," when the American Library Association's awards committees call the winners early in the morning, but you got two calls on Monday. How did that work?

So, I was lying in the bed and I was thinking I may be a contender for these particular medals but, okay, you know... maybe nothing. I'm still on New York time, but I'm in Seattle. The Coretta Scott King committee had Rudine Sims Bishop call me, and I've known Rudine since In Daddy's Arms I Am Tall (Lee & Low Books), so it was just nice to hear her voice and have her be the one who called me. And also she got a lifetime achievement award [Coretta Scott King-Virginia Hamilton Award for Lifetime Achievement], which I found out later on... she said nothing about it.

And then I figured, okay, I got the CSK, I'm happy with that, I better just start my day. So I jumped in the shower and then I got the Caldecott call, and my girlfriend was like, "Javaka, the phone! The phone!" So I was trying to turn my phone on without messing it up from being wet.

What do you think of all this?

This all just made me kind of sit and ponder. It creates a lot of possibilities. It creates a situation where people want to hear what you have to say about things. And so in that way it makes me have to be a better person. Not like you have to be good and make sure you say "hello" to everybody, just, like, who are you? What are you going to say to the world? Not like, I'm just going to fly off and say anything that comes to my mind. Now the question is, what facts do you have behind what you say? Is what you're saying based in reality? How are these things you're saying affecting the world and making it a better place?

How did you decide to create a book about Brooklyn-raised graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988)? Was he a personal inspiration to you? Or did you just like his work?

How did you decide to create a book about Brooklyn-raised graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988)? Was he a personal inspiration to you? Or did you just like his work?

All of the above. I feel like he comes from where I come from, you know? He put skelly boards in his artwork, and I played skelly in the Brooklyn streets. I ran the streets of the Lower East Side and the Village and hung out in the places he hung out at, and I've created art and, you know, it's inspiring as a young African American male growing up to see someone you know who looks like you and he's on the cover of Time magazine for his artwork. It reflects back at me because I see my experiences in his artwork.

Tell me about your relationship with New York and how it manifested itself in Radiant Child--I know you literally used parts of the city in the artwork.

I think when you're an artist, your subject matter is always yourself to a certain extent because it's always centered on something that you find really interesting. And so I really feel like me and my brother and my sisters were a part of New York City. My mother and father weren't together, so we were traveling back and forth from my mother's to my father's house. We have this great knowledge of the subways and different neighborhoods. And New York City is a place where you see, you experience almost anything. You have the richest people, you have the poorest people and everything in between. Riding the trains, I saw the graffiti and the artwork and the culture. Living in predominantly black neighborhoods and also going to the 59th Street Y. It all became food for my art.

How long did it take you to make all that art for the book?

To be honest, the labor-intensive part is more in the thinking. What am I going to do, how am I going to do it. Because it all has to make sense. It's almost like a math equation. If one plus one is not equaling two, then I have to figure out what needs to be changed.

You've been making books for a long time. How did you get your start in children's books?

My first book was In Daddy's Arms I Am Tall, and it's really weird to say I've been doing this for 20 years, but I basically have. I guess I got my start in two ways. I got my start through being the apprentice of my father [award-winning children's book creator John Steptoe]. Some of it through osmosis and some of it just asking, "How do you this, Dad? How do you do that?" And then, meeting up with Lee & Low Books because of Pat Cummings. Pat gave me Lee & Low's information and said, "Go show them your work!" I had a bunch of pictures about fathers--no, actually, they weren't about fathers, they showed men with children. Lee & Low liked those particular drawings the most, and they called me back and said let's do a book about fathers, and the rest is history.

Tell me a little bit about the physical artwork in your book.

Since I'm someone who does collage and assemblage and that type of artwork, I've created a rule for myself: I only keep a certain amount of stuff in my house and after that I have to get rid of it, because if I don't I might have to be on one of those TV shows.... When I'm working on a project, I collect materials. There's a store that sells re-used housing materials, so I got a lot from there and I also went around town--into SoHo, into the Village, the Lower East Side, I found some stuff in a Brooklyn Museum dumpster. I try to keep it as orderly as possible, so I have boxes of stuff.

When I'm working, I go into the boxes and pick out what I need and just put it together. The actual work is on a layer of plywood, which is like 1/8" or sometimes even 1/4" plywood and--just so I knew that each painting was somewhat uniform in size--I would lay down all the different blocks of wood on these plywoods. Each painting, each illustration, had its own feeling to it, so I tried to pick wood that went with that feeling.

Radiant Child is so specific in its setting and subject, but I think any creative child would feel inspired by it.

Thank you. I've been thinking a lot about genius: What is that? I think there are definitely people with special abilities. A few people have the ability to not get caught up in fear. A lot of what happens with people is that they think they can't do it, or they don't know how to do it, they don't want to be embarrassed, they don't want to look like they don't know what they're doing, and so there's this big battle in their head and what happens is they wind up not doing anything. A lot of these people who we call genius, they have a couple of things in common, and one of those things is to not worry about what other people are thinking about them. Not worry about if they sound ugly or look ugly. They do what they do. And they're going to keep doing it. And they find their way.

Is there anything else you'd like to tell the readers of Shelf Awareness?

Only that it was a labor of love. It was something that I really put my heart into, and I appreciate the love I'm getting back in return.

"Indies are thriving because of Amazon, not in spite of the Internet behemoth. This is a story of two different types of bookstores: one with vast inventory, low prices and algorithm-driven recommendations, and another that lures customers seeking tightly curated collections and a community of bookworms."

"Indies are thriving because of Amazon, not in spite of the Internet behemoth. This is a story of two different types of bookstores: one with vast inventory, low prices and algorithm-driven recommendations, and another that lures customers seeking tightly curated collections and a community of bookworms."

Winter Institute 2017 opens officially tonight, and once again there's good news about indie stores to greet booksellers: last year, some

Winter Institute 2017 opens officially tonight, and once again there's good news about indie stores to greet booksellers: last year, some  Tonight, the inaugural Young Professionals Afterparty takes place from 10-11 p.m. and aims to provide a place for young professionals in bookselling and publishing to meet and network. Several booksellers are in the

Tonight, the inaugural Young Professionals Afterparty takes place from 10-11 p.m. and aims to provide a place for young professionals in bookselling and publishing to meet and network. Several booksellers are in the  The Winter Institute's

The Winter Institute's

The Red Door Books & Art

The Red Door Books & Art

Ten Speed Press has created a new cooking and lifestyle imprint called Lorena Jones Books, which will be overseen by v-p and publisher Lorena Jones. The imprint will release six to eight illustrated and nonillustrated books annually in the areas of cooking, work life and health. The cookbooks will target committed, sophisticated, and style-conscious cooks. The titles on work life are geared to resourceful, independent-minded professionals, and the health publishing will be developed for consumers who embrace self-care ideas that are based on leading researchers' new findings and recommendations.

Ten Speed Press has created a new cooking and lifestyle imprint called Lorena Jones Books, which will be overseen by v-p and publisher Lorena Jones. The imprint will release six to eight illustrated and nonillustrated books annually in the areas of cooking, work life and health. The cookbooks will target committed, sophisticated, and style-conscious cooks. The titles on work life are geared to resourceful, independent-minded professionals, and the health publishing will be developed for consumers who embrace self-care ideas that are based on leading researchers' new findings and recommendations.

In "an effort to expand exposure to its bookstore members and their customers to books by people of color," the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance will

In "an effort to expand exposure to its bookstore members and their customers to books by people of color," the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance will  On the afternoon of Saturday, March 11, Simon & Schuster is hosting the

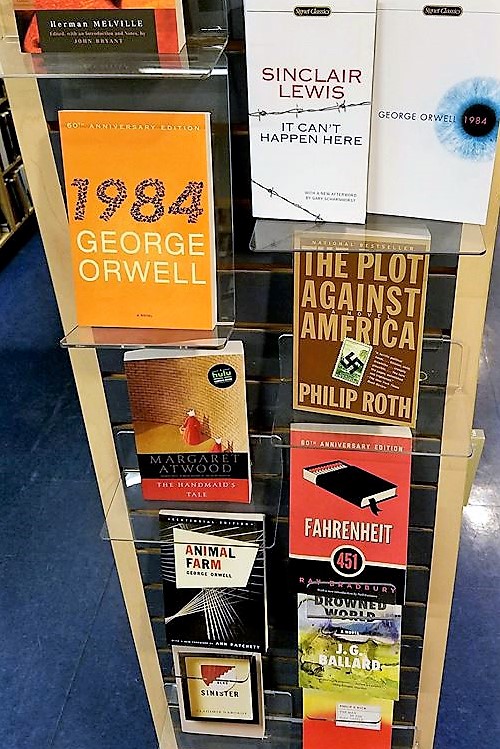

On the afternoon of Saturday, March 11, Simon & Schuster is hosting the  Following the presidential inauguration a week ago, dystopian fiction has become so popular that 1984 by George Orwell has jumped to the top of some bestseller lists, is in demand at libraries, and Penguin has gone back to press for another 75,000 copies of the Signet Classics mass market edition of the 1949 novel, which gave the world the phrases Big Brother, newspeak, doublethink and more.

Following the presidential inauguration a week ago, dystopian fiction has become so popular that 1984 by George Orwell has jumped to the top of some bestseller lists, is in demand at libraries, and Penguin has gone back to press for another 75,000 copies of the Signet Classics mass market edition of the 1949 novel, which gave the world the phrases Big Brother, newspeak, doublethink and more.  Tsutaya

Tsutaya From the Facebook page of

From the Facebook page of

Bunnybear

Bunnybear_Gregg_Richards_012517.jpg)

How did you decide to create a book about Brooklyn-raised graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988)? Was he a personal inspiration to you? Or did you just like his work?

How did you decide to create a book about Brooklyn-raised graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988)? Was he a personal inspiration to you? Or did you just like his work?_John_Swannell.jpg)

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for: Less a debut and more an arrival, this arresting first novel from Yoojin Grace Wuertz brings to life a South Korea poised on the brink of transformation and the young people caught up in its turbulence.

Less a debut and more an arrival, this arresting first novel from Yoojin Grace Wuertz brings to life a South Korea poised on the brink of transformation and the young people caught up in its turbulence.

It's quite possible that while you are reading this Friday morning, I'm on a flight to Minneapolis, where I'll have the pleasure of covering the 12th annual

It's quite possible that while you are reading this Friday morning, I'm on a flight to Minneapolis, where I'll have the pleasure of covering the 12th annual  The January 30, 2006 edition of Shelf Awareness featured the first of several pieces on the inaugural conference, under the headline: "Grade for ABA's First Winter Institute: A+." The piece noted that the nearly 400 attendees "had nothing but praise for the event. The mood was relaxed but intense, and many remarked on how easy it was to talk shop and socialize. Several industry veterans went so far as to call it the best bookseller-oriented event they had ever attended."

The January 30, 2006 edition of Shelf Awareness featured the first of several pieces on the inaugural conference, under the headline: "Grade for ABA's First Winter Institute: A+." The piece noted that the nearly 400 attendees "had nothing but praise for the event. The mood was relaxed but intense, and many remarked on how easy it was to talk shop and socialize. Several industry veterans went so far as to call it the best bookseller-oriented event they had ever attended."