Michel de Montaigne turned 485 years old February 28 and is still reading well for his age. Last Friday, I went to an author event at the Northshire Bookstore in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., featuring Michael Perry, author of Montaigne in Barn Boots: An Amateur Ambles Through Philosophy (Harper).

|

|

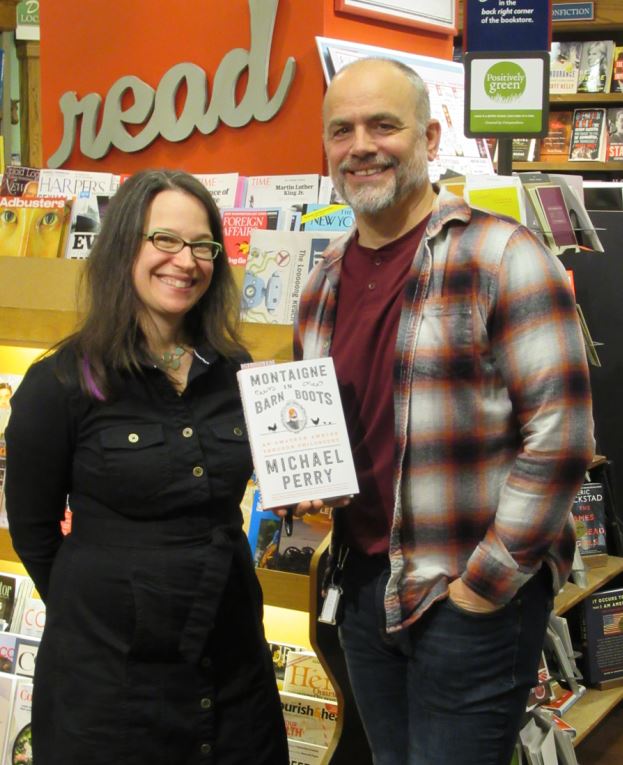

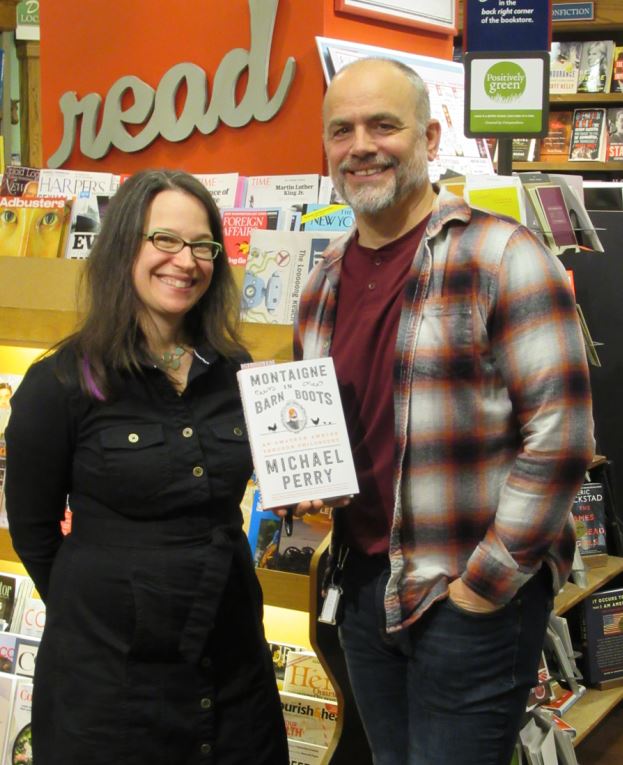

Rachel Person, events & community outreach coordinator for the Northshire Bookstore, Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and author Michael Perry

|

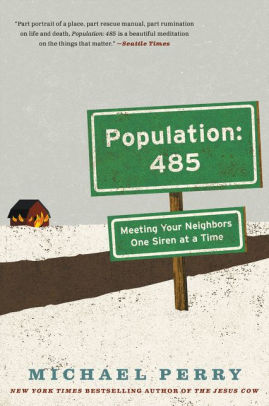

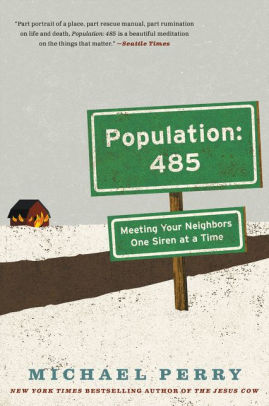

We first met in 2002, when I was a bookseller at the Northshire's Manchester Center, Vt., store and he was touring for Population: 485: Meeting Your Neighbors One Siren at a Time. On Wednesday, Perry duly noted the curious "Montaigne and the 485 Singularity." For the record, I did not play 4-8-5 in the N.Y. State Lottery daily numbers game. I got lucky; it didn't come in.

I've been one of Perry's many dedicated readers for more than 15 years now. We've also had a few good conversations over the years, both here in the Northeast and at bookseller conferences in the Midwest. Despite the geographical differences in our upbringing (his in Wisconsin; mine in Vermont), we have some things in common and our all-too-brief chats are always a fair trade of good thoughts. I like the way he thinks, and writes, about life. And maybe that's why we both like Montaigne.

In the introduction to his new book, Perry observes that his goal was to "write of Montaigne in terms of exploration rather than declaration. I admit the angle of my appreciation lacks academic rigor, but I believe Montaigne would not object: he shares up-culture and down-culture with equivalent alacrity, operating under the hearty assumption that your appetite for Seneca's interrogatories on courage neither precludes nor prevents your giggling at a fart joke."

Introducing his younger daughter to the synergy between going to a performance of Shakespeare's Twelfth Night and a demolition derby on the same weekend ("groundlings" is one connection), he strikes a familiar chord. My wife has noted more than once my habit of reading great, and lesser, works of literature while watching NASCAR (Those races are long, man!).

Perry was in the Northeast for a brief drive-yourself book tour. "I'm grateful to Harper and the northeastern indies for supporting a DIY-style tour well outside my regional base," he told me. "I've been doing things that way since my first self-published book, and I think independent booksellers relate to the hustle-to-survive ethos. Working to find readers. I stretched the tour budget by operating out of a friend's farmhouse located centrally to all my New York and Connecticut stops. Lots of driving, but that is some beautiful country."

Perry was in the Northeast for a brief drive-yourself book tour. "I'm grateful to Harper and the northeastern indies for supporting a DIY-style tour well outside my regional base," he told me. "I've been doing things that way since my first self-published book, and I think independent booksellers relate to the hustle-to-survive ethos. Working to find readers. I stretched the tour budget by operating out of a friend's farmhouse located centrally to all my New York and Connecticut stops. Lots of driving, but that is some beautiful country."

He is quick to acknowledge his debt to indies: "In 2002 I was this unknown writer from the rural Midwest hustling a book about small towns and volunteer firefighters/EMTs. Someone in New York told me they weren't sure 'those folks' would read a book. Indie booksellers on the other hand--especially those in less populous areas--understood the 'vollie' culture and how it permeated the country, and handsold me into existence by conveying that element of the book to their customers--not just in the Midwest, but all around America. They also knew when to switch gears and emphasize other elements of the book, depending on the customer. Population 485 is still alive and well and thriving thanks to indie booksellers who continue to not only tell its story but understand it."

We've talked more than once about writing as both work and calling. "At this stage in my life, I think of 'work' as anything that a.) gives me the sense that I am making some useful forward progress, and b.) simultaneously helps keep my little family fed and housed," Perry said. "So, stacking firewood and finishing a newspaper column both count. Because of my background (farming, logging) I still have a big blue-collar hangover, that whole idea (as I've written) that if you can't stack it or stack with it, it ain't real work. (And a stack of books doesn't count.) For the most part this predisposition keeps me grounded and grateful, but it can also become pathological and lead to a lot of dumb stubbornness. With each passing day I am ever more grateful to those writers and other artists in my life who help me understand the value lies not so much in what you work but in how you work. How and why."

During q&a at the Northshire event last week, a student from the local college said one of her English professors had told her she was sometimes too discursive in her essays, a little overfond of "shiny thoughts." She wanted Perry's take on that criticism. I liked his answer.

"I sometimes get very discursive," Perry replied. "So it's not so much getting rid of all those shiny thoughts, but it's knowing which ones to get rid of and then which ones to let breathe and run. In the book, I write about Montaigne saying how delightful it is when the prose goes by 'the gait of poetry, all jumps and tumblings,' and I love that.... I love the way language flows and sounds, the way I see it in my head.... and so sometimes in the books you let that stuff go."

Near the end of his talk, Perry thanked his audience members for being there: "When you show up for events like this, and you buy a book, you're not just supporting art, you're taking care of my family, and I do not take that for granted." It was a good night to be in a bookstore.

Stillwater Books, a new independent bookstore selling both new and used books, opened yesterday with a ribbon-cutting ceremony in downtown Pawtucket, R.I., the Valley Breeze reported. The store's inventory features a large selection of titles by local, Rhode Island authors, and in addition to books Stillwater carries cards and some gift items.

Stillwater Books, a new independent bookstore selling both new and used books, opened yesterday with a ribbon-cutting ceremony in downtown Pawtucket, R.I., the Valley Breeze reported. The store's inventory features a large selection of titles by local, Rhode Island authors, and in addition to books Stillwater carries cards and some gift items.

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.S1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

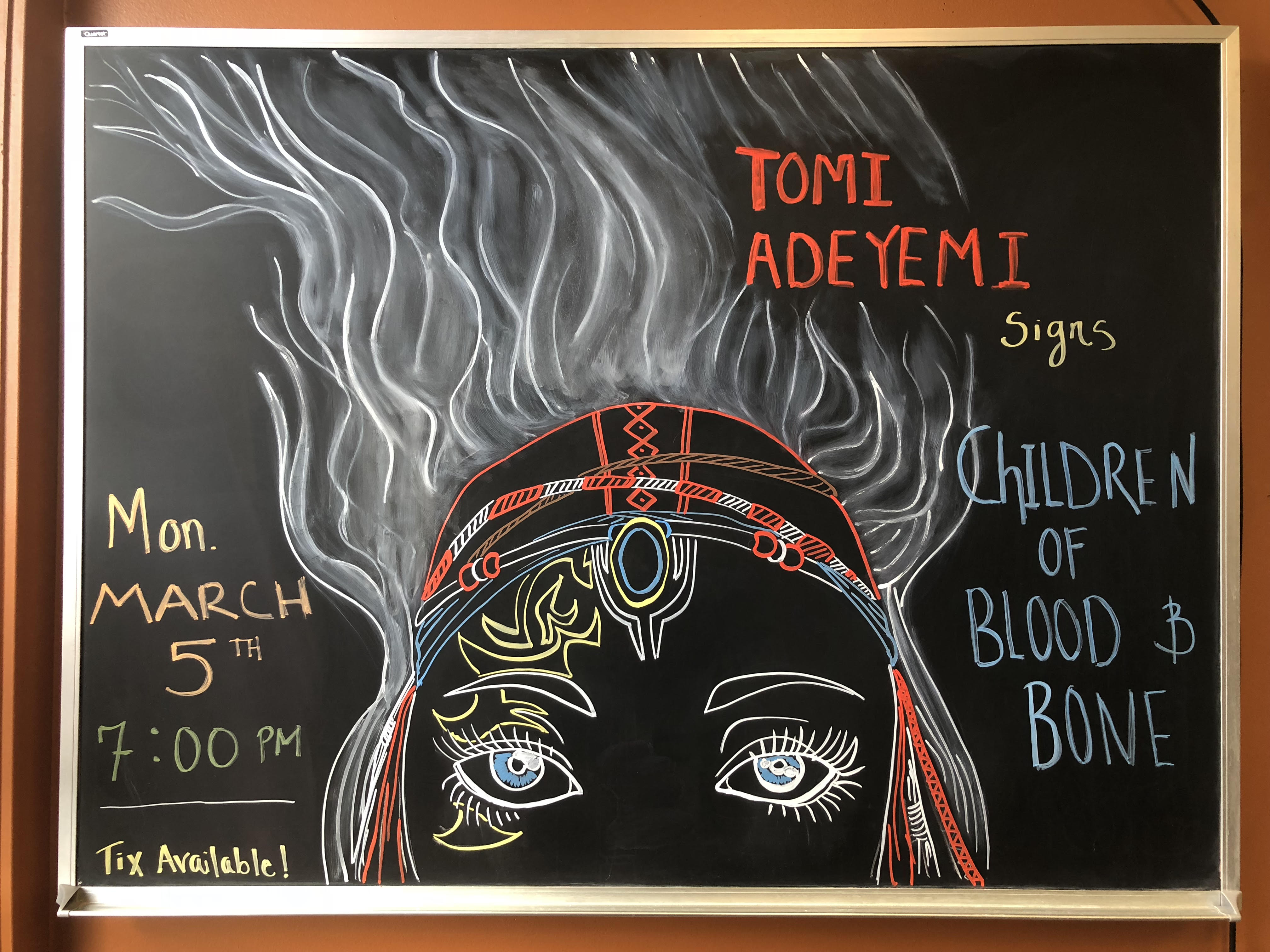

Trident Booksellers and Café

Trident Booksellers and Café

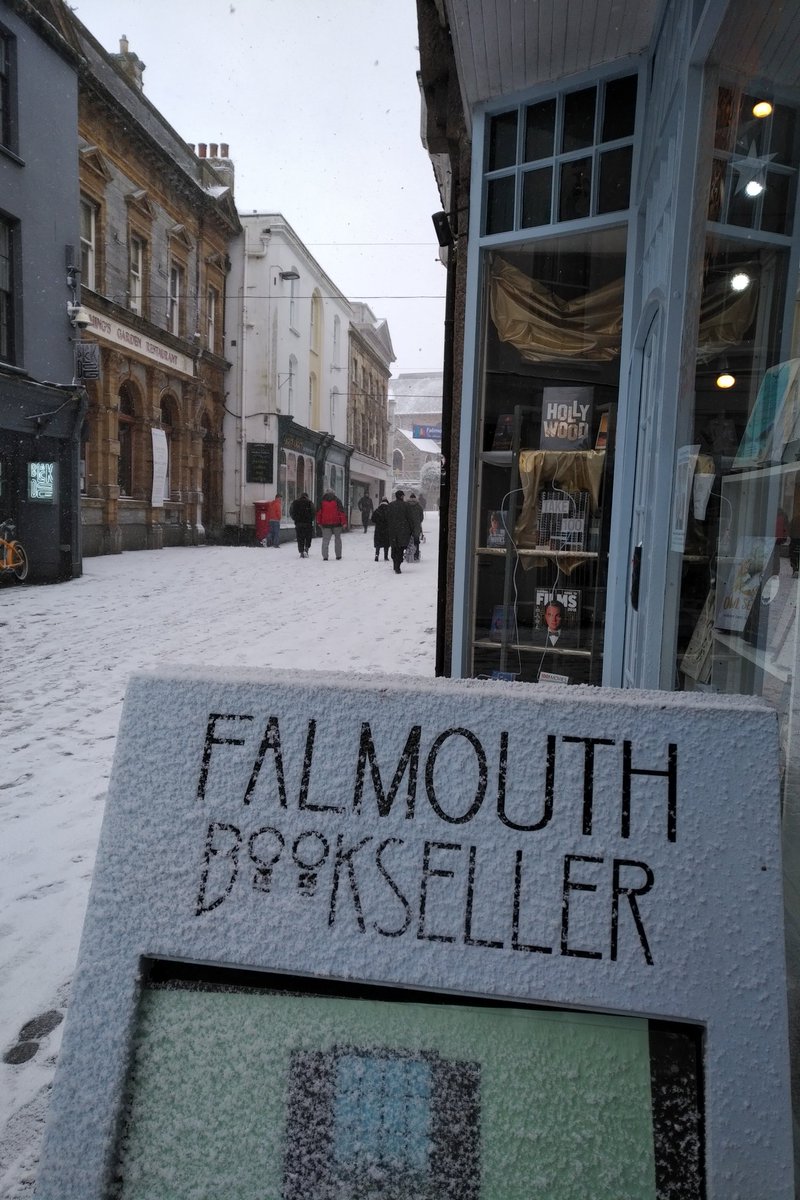

As weather alerts went up across the U.K. and Ireland and Storm Emma brought snow, wind and travel warnings,

As weather alerts went up across the U.K. and Ireland and Storm Emma brought snow, wind and travel warnings,

.jpg)

"Amazon might be able to recommend titles based on what you've read before, but its algorithms can only make educated guesses at how you're feeling. For a shrewd, intuitive choice--one that might run counter to your previous reading--you need Drew Cohen," the Sun wrote, referring to the bookshop's co-owner.

"Amazon might be able to recommend titles based on what you've read before, but its algorithms can only make educated guesses at how you're feeling. For a shrewd, intuitive choice--one that might run counter to your previous reading--you need Drew Cohen," the Sun wrote, referring to the bookshop's co-owner. Maryelizabeth Yturralde, co-owner of

Maryelizabeth Yturralde, co-owner of  Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden and

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden and  The Thrifty Guides to the World

The Thrifty Guides to the World

Book you're an evangelist for:

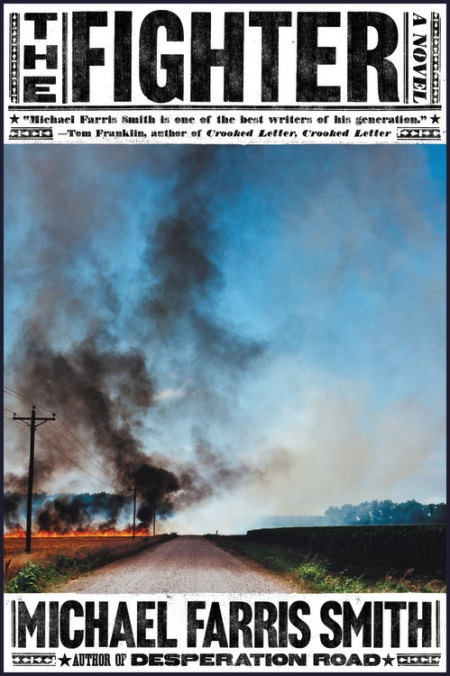

Book you're an evangelist for: Set in the famous blues crossroad town of Clarksdale, Miss., Michael Farris Smith's third novel (after

Set in the famous blues crossroad town of Clarksdale, Miss., Michael Farris Smith's third novel (after

Perry was in the Northeast for a

Perry was in the Northeast for a