|

| Friedrich Elfers and Barbara Perlmutter (photo: John Harris) |

Last week at the Festival Neue Literatur in New York, the Friedrich Ulfers Prize, honoring "a publisher, writer, critic, translator, or scholar who has championed the advancement of German-language literature in the United States," was given to publisher Barbara Perlmutter.

In his Laudatum for Perlmutter, Bob Weil, editor-in-chief and publishing director for Liveright, said, in part:

"A chance set of circumstances resulted in the Berlin-born Barbara Perlmutter coming to America in 1965. Having already studied English in London and deciding that Paris was too saturated with her college friends, she opted for Spain, where she met in a class for foreign students, a young American, who had just arrived in Madrid via Santo Domingo. 'The attraction was pretty immediate,' Barbara recalls about Dan Perlmutter, who seemed very different from the German men she had known, and whose progressive ideas were quite appealing, so much so that she soon found herself a young bride, first in Minnesota, where she worked at a photo lab, and then on the Upper East Side in Yorkville, where German could be overheard on 86th Street, and where Kaffee und Kuchen could be had at the Heidelberg or Bremen-Haus.

"While the circumstances of her arrival in America might have been fortuitous, little else about this extraordinary woman’s career are, I emphasize, as we celebrate her winning the prestigious award that recognizes a recipient's lifetime achievements in the dissemination of German literature in the United States. In Barbara's case, I cannot think of a worthier person, whose overall contributions far exceed her official title as a scout and agent for S. Fischer Verlag. Never, in fact, let her modest demeanor ever fool you because the influence she has wielded since 1965, when she answered a two-line ad in the New York Times and began working as Joan Daves's assistant, has cumulatively had a profound effect on the very existence of German literature in America, as significant as that of her illustrious predecessors, among them, Helen Wolff, America's first Kafka editor, whom Barbara knew as a young woman, the formidable Joan Daves, with whom she worked for 13 years before breaking out to work with S. Fischer on her own--as well as legendary editors like Drenka Willen, Carol Janeway, and her beloved friend, Sara Bershtel, whom she knew even before Sara began her own distinguished publishing career. Barbara's longevity as a force in German-American publishing is simply unrivaled, this being her 55th year, and though she claims to be retired, don't be so sure.

"To follow her career then is to follow the very undulations of German publishing in America for half a century, and while the 1960s may have seemed the apogee with the popularity of authors, such as Franz Werfel, Elias Canetti, Carl Zuckmayer, and Hermann Hesse, this current decade has witnessed the publication of the final volumes of Reiner Stach's three-volume Kafka biography, the forthcoming translated publication of the unexpurgated Kafka Diaries, and the forthcoming English publication of Alfred Döblin's Berlin Alexanderplatz, three discrete projects in which Barbara has been critically involved. To think of her then as a mere agent would be a serious misnomer, for given her nuanced knowledge of German and English literature, Barbara is both scholar and secret academic, bringing an understanding to both languages that is remarkable. I've known this personally for quite a long time in that the first book I ever acquired in my career was a Holocaust memoir, which Barbara sold to a skinny 23-year-old editorial assistant in that pre-computer, pre-Internet year of 1978, and last week she could still pull out correspondence on onion-skin paper that affirmed that she had helped salvage a problematic translation that resulted in a notable and important publication."

Perlmutter remembered, in part:

"When, in the mid-'60s, I began my work for Joan Daves, a prominent literary agent at the time, communication with German publishers was quite different from today. A shipment of galleys was prepared with a label 'by sea mail' and the New York Times provided the date and time the next ship would leave the harbor--and delivery to that ship would be requested.

"That was a high time for German authors in New York: Uwe Johnson, Hans-Magnus Enzensberger, Heinrich Böll, Peter Weiss and the Swiss author Max Frisch, whose story Montauk is still 'the' insider story of that time. (I'd like to add, we had to prod the Times into adding an umlaut to their typefaces, so Heinrich Böll was no longer Herr Boell.)

"I began work for S. Fischer Verlag in fall of 1978. What I found was a trove of the most important German-language literature and, beside my work as scout, I helped keep in print S. Fischer's classics--and find publishers for their young authors.

"Via telegram, dictated to a non-German-speaking operator, I reported my first sale in November '78: 'Joachim-Ernst Berendt's Das Jazz Buch.' It's still in print...

"So many translators need to be thanked. Michael Hofmann, Shelley Frisch (who translated three monumental volumes of Reiner Stach's Kafka biography), Margot Dembo (who labored over Judith Hermann's prose) and David Dollenmayer, who translated for NYU Press Andreas Bernard's book about elevators. Without their efforts, none of our German authors would have made it here.

"My very last book project was--still is--a major one: When I read in Ian Buruma's film critique of Berlin Alexanderplatz that the novel by Alfred Döblin was untranslatable and the existing one awful, I turned to Edwin Frank. It was a daunting job, indeed, but New York Review of Books is publishing Michael Hofmann's translation, now in March. Altogether, it took some 10 years from sample translation to finished book."

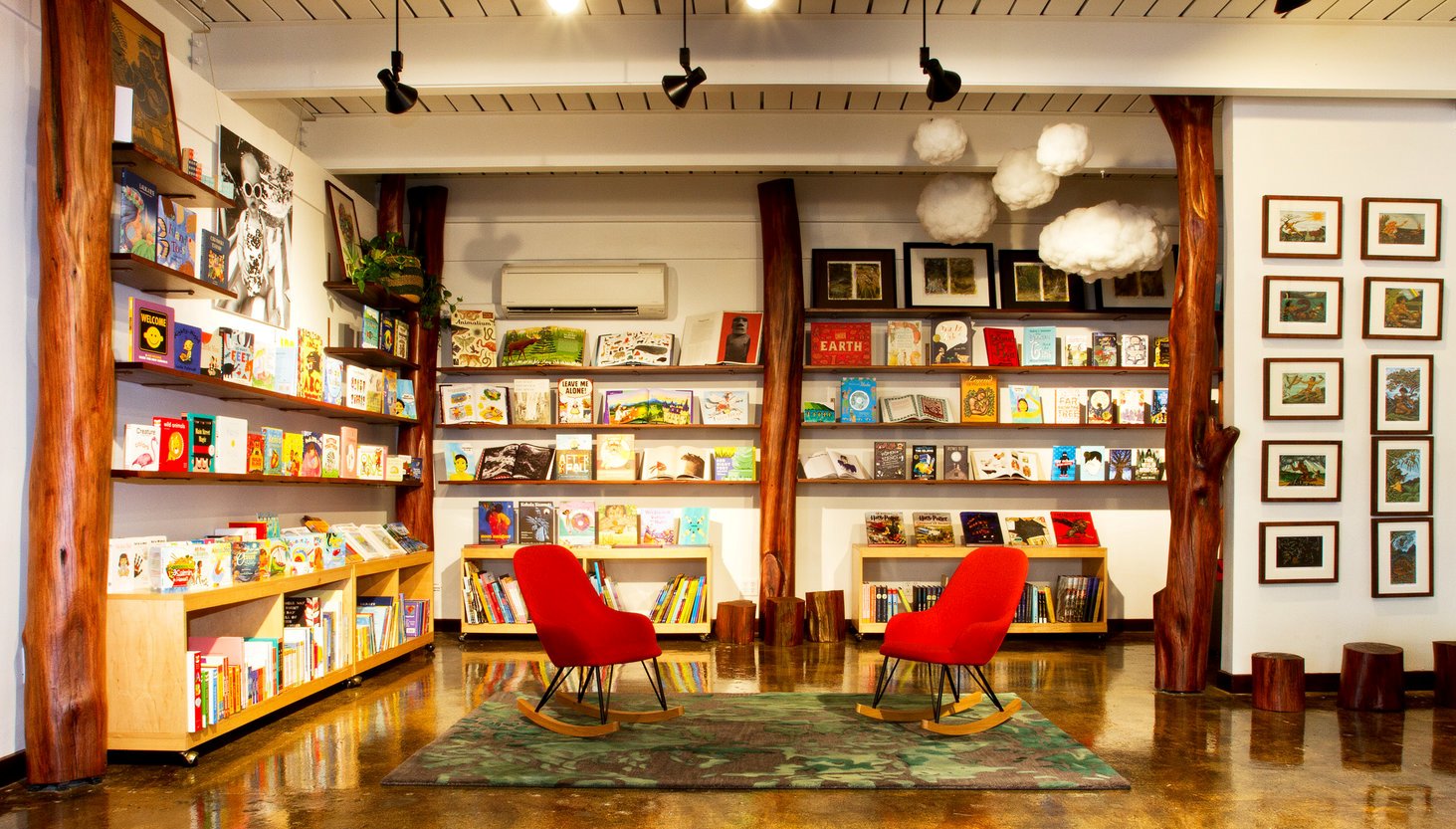

da Shop, a bookstore founded by indie publisher Bess Press, opened this week in Kaimuki in Honolulu, Hawaii, Honolulu magazine reported. The store held its grand opening on March 27, with an event featuring Patagonia Surfing Ambassador Liz Clark, who discussed her memoir, Swell: A Sailing Surfer's Voyage of Awakening, which Patagonia will publish next week.

da Shop, a bookstore founded by indie publisher Bess Press, opened this week in Kaimuki in Honolulu, Hawaii, Honolulu magazine reported. The store held its grand opening on March 27, with an event featuring Patagonia Surfing Ambassador Liz Clark, who discussed her memoir, Swell: A Sailing Surfer's Voyage of Awakening, which Patagonia will publish next week.

SHELFAWARENESS.0213.S4.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

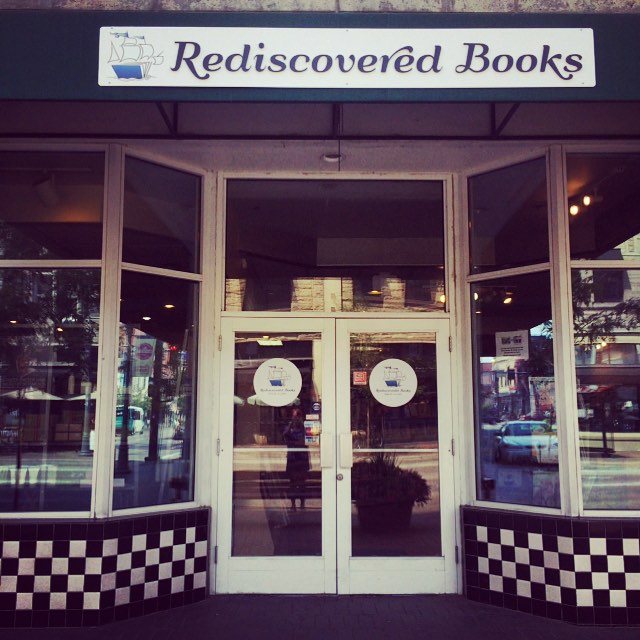

Laura and Bruce DeLaney, owners of

Laura and Bruce DeLaney, owners of

Effective with the ABC Children's Institute June 19-21, the American Booksellers Association has adopted a code of conduct for all association meetings and events. The ABA is encouraging member stores to adapt the code for their events and to offer feedback, which may lead to additions or changes. Booksellers with comments or questions can

Effective with the ABC Children's Institute June 19-21, the American Booksellers Association has adopted a code of conduct for all association meetings and events. The ABA is encouraging member stores to adapt the code for their events and to offer feedback, which may lead to additions or changes. Booksellers with comments or questions can SHELFAWARENESS.0213.T3.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

Barnes & Noble has launched

Barnes & Noble has launched

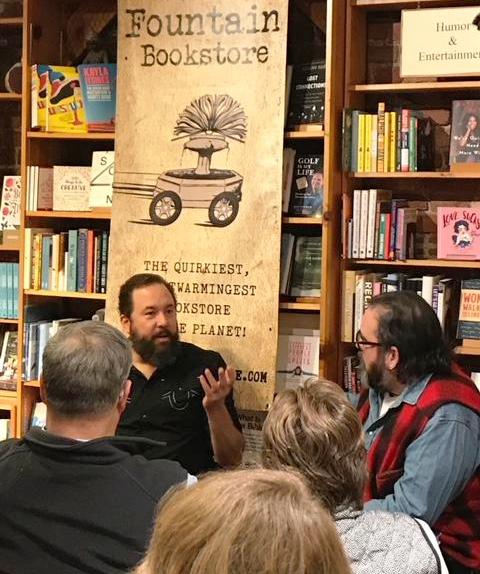

Yesterday afternoon,

Yesterday afternoon,  "Are you longing to lose yourself in a good read?" asked the Associated Press to introduce a slide show tempting readers to "consider

"Are you longing to lose yourself in a good read?" asked the Associated Press to introduce a slide show tempting readers to "consider  What Is Soft?

What Is Soft? As a child preparing for her first confession, essayist Patricia Hampl (The Florist's Daughter) learns from the Examination of Conscience that daydreaming is a sin. "I don't hesitate. I throw my lot with the occasion of sin. I already know (or believe--which comes to the same thing in my Catholic worldview) that daydreaming doesn't make things up. It sees things.... I couldn't care less what it's called. It's pure pleasure. Infinite delight. For this a person goes to hell. Okay then."

As a child preparing for her first confession, essayist Patricia Hampl (The Florist's Daughter) learns from the Examination of Conscience that daydreaming is a sin. "I don't hesitate. I throw my lot with the occasion of sin. I already know (or believe--which comes to the same thing in my Catholic worldview) that daydreaming doesn't make things up. It sees things.... I couldn't care less what it's called. It's pure pleasure. Infinite delight. For this a person goes to hell. Okay then."