Donald Hall, "a giant of American poetry," died June 23 at Eagle Pond Farm in Wilmot, N.H., "where he hayed with his grandfather during boyhood summers and later cultivated a writer's life," the Concord Monitor reported. He was 89. Hall was "a literary dynamo, writing poetry, memoir, criticism, magazine articles, plays, short stories and children's books." In addition to winning numerous awards and honors, Hall was appointed U.S. poet laureate in 2006 by President George W. Bush. President Barack Obama awarded him the National Medal of the Arts in 2010.

He wrote almost to the end of a career that spanned more than 60 years, beginning with the publication at 26 of his poetry collection Exiles and Marriages and continuing through his Essays after Eighty (2014) and soon-to-be-published A Carnival of Losses: Notes Nearing Ninety. His last poetry collection, The Selected Poems of Donald Hall, was released in 2015.

In 1972, five years after a divorce, Hall married Jane Kenyon, his former student at the University of Michigan. They eventually moved to the New Hampshire farm his family had owned for a century, a decision that "transformed his poetry," beginning with Kicking the Leaves (1978), as well as his life, the Monitor noted, adding that the "Hall-Kenyon literary household peaked in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Kenyon wrote two popular collections--Let Evening Come in 1990 and Constance in 1993. Hall turned his poem 'The Ox-Cart Man' into a children's book that sold well for years. His book-length poem, The One Day, won the National Book Critics Circle Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer."

After Kenyon's leukemia diagnosis in 1993 and death at 47 in 1995, Hall's "grief ran long and deep," the Monitor wrote. He shepherded her book Otherwise to publication, appeared at events celebrating her life and work, and wrote poems (Without, 1999; The Painted Bed, 2003) and a memoir (The Best Day the Worst Day: Life with Jane Kenyon, 2006) about losing her. "Twenty years later, he still teared up talking about her," the Monitor noted.

"One does write, indeed, to be loved," Hall told the Boston Globe in 1985. "Fame is another word for love, an impersonal word for love. One wants people 200 years from now to love your poetry. The great pleasure of being a writer is in the act of writing, and surely there is some pleasure in being published and being praised. I don't mean to be complacent about what I have some of. But the greater pleasure is in the act. When you lose yourself in your work, and you feel at one with it, it is like love."

In 2012, he announced that his poetry-writing days were over, and in a New Yorker essay, "Out the Window," he observed: "New poems no longer come to me, with their prodigies of metaphor and assonance. Prose endures. I feel the circles grow smaller, and old age is a ceremony of losses, which is on the whole preferable to dying at forty-seven or fifty-two. When I lament and darken over my diminishments, I accomplish nothing. It's better to sit at the window all day, pleased to watch birds, barns, and flowers. It is a pleasure to write about what I do."

From his poem "Affirmation":

Let us stifle under mud at the pond's edge

and affirm that it is fitting

and delicious to lose everything.

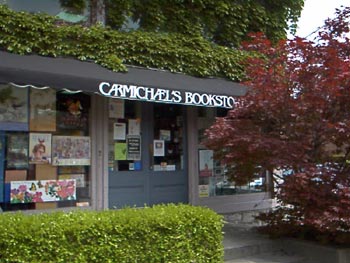

Carmichael's Bookstore, Louisville, Ky., is expanding its general store at 1295 Bardstown Road, adding 750 square feet of space, WDRB reported. The space had been occupied by Heine Brothers Coffee, which has moved across the street.

Carmichael's Bookstore, Louisville, Ky., is expanding its general store at 1295 Bardstown Road, adding 750 square feet of space, WDRB reported. The space had been occupied by Heine Brothers Coffee, which has moved across the street.

IPC.0204.S3.INDIEPRESSMONTHCONTEST.gif)

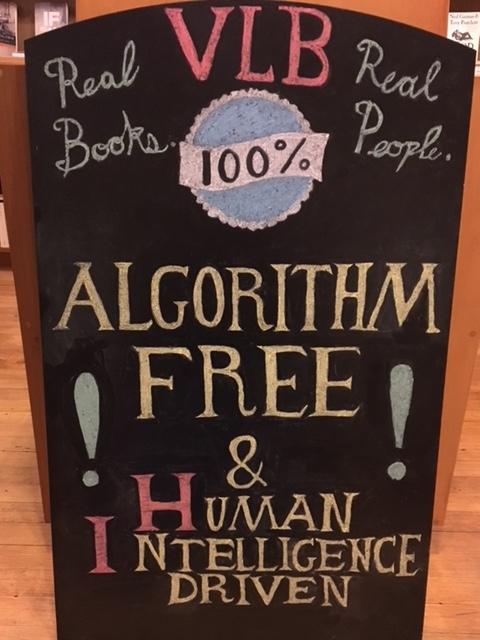

At Children's Institute 6 in New Orleans, La., last week, author Angie Thomas (The Hate U Give and the forthcoming On the Come Up, Harper) delivered a charming and passionate final keynote. "I'm here," Thomas said, "to beg you to change our world." Acknowledging that this was a big ask, Thomas went on to explain how important gatekeepers had been in her life and in her journey to being an author. She told the story of her first-grade teacher ("Mrs. First"), whom Thomas overheard complaining to a coworker that educating black youth was a waste of time. In contrast, her third-grade teacher ("Mrs. Third") saw Thomas's love of writing and nurtured it. Both teachers were white, both teachers saw her blackness and both teachers made her want to be her best self, except one galvanized and one encouraged. What kind of gatekeeper, she asked the crowd, are you? What kind of gatekeeper do you want to be? "Do you know who you're providing books to?"

At Children's Institute 6 in New Orleans, La., last week, author Angie Thomas (The Hate U Give and the forthcoming On the Come Up, Harper) delivered a charming and passionate final keynote. "I'm here," Thomas said, "to beg you to change our world." Acknowledging that this was a big ask, Thomas went on to explain how important gatekeepers had been in her life and in her journey to being an author. She told the story of her first-grade teacher ("Mrs. First"), whom Thomas overheard complaining to a coworker that educating black youth was a waste of time. In contrast, her third-grade teacher ("Mrs. Third") saw Thomas's love of writing and nurtured it. Both teachers were white, both teachers saw her blackness and both teachers made her want to be her best self, except one galvanized and one encouraged. What kind of gatekeeper, she asked the crowd, are you? What kind of gatekeeper do you want to be? "Do you know who you're providing books to?"

Barnes & Noble is creating its first dedicated graphic novel sections for readers ages 7-12. The sections will feature more than 250 titles, including popular series such as Amulet, Wings of Fire and Nathan Hale's Hazardous Tales. The sections will include graphic novels in fiction, fantasy & adventure, history, and science.

Barnes & Noble is creating its first dedicated graphic novel sections for readers ages 7-12. The sections will feature more than 250 titles, including popular series such as Amulet, Wings of Fire and Nathan Hale's Hazardous Tales. The sections will include graphic novels in fiction, fantasy & adventure, history, and science.IPC.0211.T4.INDIEPRESSMONTH.gif)

Bruce Lee: A Life

Bruce Lee: A Life Adored by his family and admired by his community for a life of good works, Harry Tabor is a man who seems to have it all and to appreciate the good fortune that has brought him to this place at age 70. But as Cherise Wolas (

Adored by his family and admired by his community for a life of good works, Harry Tabor is a man who seems to have it all and to appreciate the good fortune that has brought him to this place at age 70. But as Cherise Wolas (