|

| photo: Ryan LeBreton |

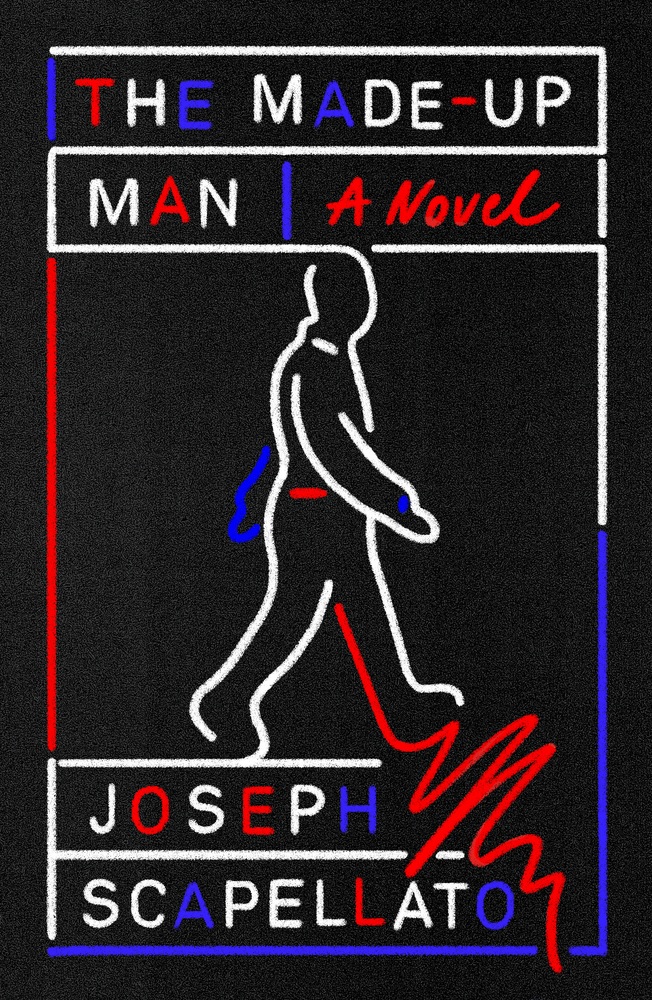

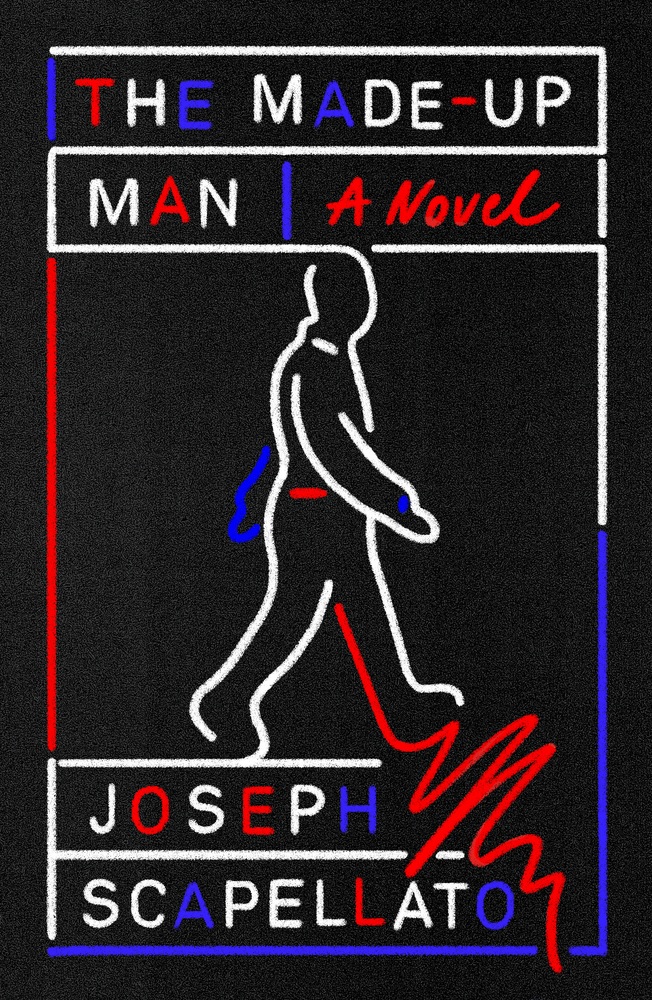

Joseph Scapellato is the author of the story collection Big Lonesome (2017) and the novel The Made-Up Man (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, February 5, 2019). He earned his MFA in fiction at New Mexico State University and has been published in Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, Post Road and other literary magazines. His work has been anthologized in Forty Stories, Gigantic Worlds: An Anthology of Science Flash Fiction and The Best Innovative Writing. Scapellato is an assistant professor of English in the creative writing program at Bucknell University. He grew up in the suburbs of Chicago and lives in Lewisburg, Pa., with his wife, daughter and dog.

On your nightstand now:

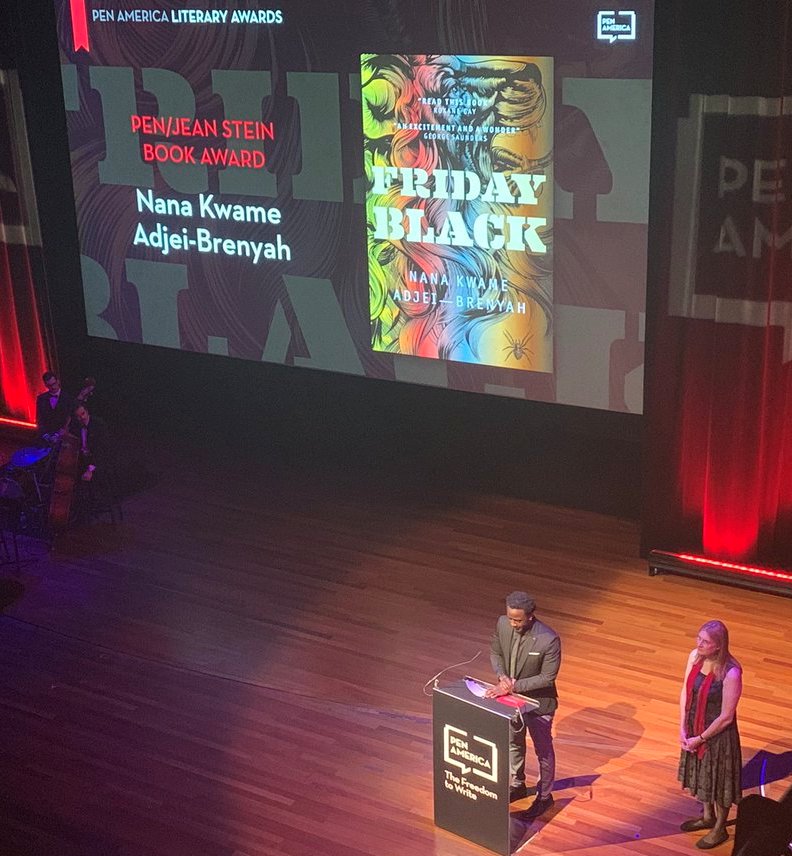

Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang, The Ensemble by Aja Gabel, The Electric Woman by Tessa Fontaine and Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah. (My nightstand is a little crowded!) All four have got me hooked.

Favorite book when you were a child:

A three-way tie between My Father's Dragon by Ruth Stiles Gannett, D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths and D'Aulaires' Book of Norse Myths. Each takes the reader right into the center of a richly wondrous world.

In My Father's Dragon, the protagonist, who is only ever referred to as "my father," travels to an island to rescue a baby dragon. His journey is adventurous and fun, but the narrator's use of retrospective distance--the fact that the father's childhood is long gone--gives the book a quietly beautiful note of elegy.

What I love about the D'Aulaires' books (aside from the incredible illustrations) is how they respect a kid's intelligence. In mythology, bad things happen for bad reasons, and sometimes the bad results of those bad things can't ever be undone. Baldur, murdered by Loki, can't come back from the dead, even though the gods get the stones to weep; Daphne, transformed into a tree to escape her would-be rapist, Apollo, can't turn back into a person. Even the most sheltered childhood can be terrifying and irreversible and unfair. Not every children's book represents this reality in an approachable way.

Your top five authors:

This is an impossible question! But here's my answer, for today: Russell Hoban and Clarice Lispector amaze me. They're myth-minded writers who aren't afraid of sentence-level poetics, who consistently make the abstract concrete and the concrete abstract. Laura van den Berg and Charles Yu write work that is somehow able to abound in intellectual firepower, and at the same time, hang close to the heart; their fiction is magnificently real, even when it "isn't." And Richard Brautigan will always be a writer who I return to when I need to recharge myself. (I intentionally haven't read all of his books yet because I want to save some for when I really need them.) Everything that I've said about the previous four writers applies to Brautigan, too; all I'd add is that he occasionally pushes his work so hard that it fails, which I love and admire and respect.

Book you've faked reading:

I'm woefully deficient in 19th-century English-language classics. At various points in my life, I have, by saying nothing, permitted highly cultured colleagues of mine to conclude that I've read any number of novels by Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, Henry James and the like. (I'm not proud of this!)

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz by Russell Hoban. According to my Internet order history, I've given this book to at least six people over the last 10 years. When I first read it, back in 2008, I was absolutely stunned. Hoban was doing what I wanted to try to do. He's somehow able to make his language enact--not just impart--a range of unanswerable emotional/existential mysteries, the shores of which his characters continually shipwreck themselves upon. And he's funny!

Book you've bought for the cover:

Quite a few titles from Open Letter Books (Frontier by Can Xue), Archipelago Books (Distant Light by Antonio Moresco) and Black Ocean (At Night by Lisa Ciccarello). And let me tell you: the covers do not deceive. These three presses consistently put out spectacular (and beautifully designed) prose and poetry.

Book you hid from your parents:

In high school, I bought Numerology: The Complete Guide by Matthew Oliver Goodwin. For some reason, I was embarrassed at the thought of my parents finding it. It's not that they would've put forward some sort of unreasonable religious rejection--it's that they would've lost respect for me. So I stashed it in my bedroom.

I still have this book. I just looked at it, moments ago, for the first time in a decade. Tucked between the pages are sheets of scratch paper on which I exhaustively calculated the Life Path, Expression and Soul Urge numbers for friends, family and ex-girlfriends. Apparently, when it came to the occult, I was willing to do math.

Book that changed your life:

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown. I read it in high school, though not for any class. I knew that white settlers orchestrated the genocide of every Native American people they encountered, but it wasn't until I read that book that I was given a sense of the harrowing extent of the genocide's sustained intentionality. This was never a story that my teachers discussed in any meaningful way in grade school, junior high or high school. This book opened my eyes to the fact that my generation had been raised on an unforgivably simplified version of American history.

Favorite line from a book:

In the introduction to Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace, translators Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky refer to a moment when Tolstoy, responding to critics, declared, "The hero [of this novel] is truth." I love this statement. I love how it's bold and idealistic. I even love how it's perhaps a little pompous or absurd. Whether or not such a statement can be true about a novel (or a poetry collection, or a work of nonfiction), a book in which the "hero" is "truth" is the kind of book that I want to read--the kind of book where the writer is committed to taking the risk of telling the truth-as-they-have-felt-it, where the book's style, however strange and unconventional it might be, is ecstatically in the service of that truth.

Five books you'll never part with:

When I was in junior high and high school, I played a lot of tabletop roleplaying games: mainly Dungeons & Dragons, Cyberpunk 2020, Werewolf, Mage, Vampire and Rifts. Although I don't really play anymore--my very oldest friends and I get together for a one-night session of Cyberpunk 2020 maybe once a year--I still can't quite bring myself to sell or donate my RPG books. For me, they've always been emblems of potentiality, invitations to endlessly co-create characters, worlds, stories. I know this doesn't make sense, but if I were to get rid of them, I would be saying no to something that I've made it my job to say yes to.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban. In this experimental post-apocalyptic novel, the narrator speaks in an imagined future version of English.

Here's the first sentence:

"On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wyld boar he parbly ben the las wyld pig on the Bundel Downs any how there hadnt ben none for a long time befor him nor I aint looking to see none agen."

When I read this book for the first time, I was struck with so much confused delight that as soon as I finished a chapter, I immediately reread it, partly because I wanted to understand more of the language, and partly because I wanted to understand why I loved not understanding everything about the language.

I won't ever be able to have that experience with this book again.

Books you love reading to kids:

My daughter is two years old and loves books. (Thank goodness!) There are so many excellent books for toddlers, but I especially love sitting down with Silly Sally by Audrey Wood, Chicka Chicka Boom Boom by Bill Martin, Jr. and John Archambault, and Bunny Roo, I Love You by Melissa Marr. My daughter is now old enough to participate in reading--she loves to finish sentences--and each of these books can make a lovely game of that.

"Amazon is a commercially driven organization of extreme vigor, and everything indicates that that internal dynamic within its nature... Amazon is definitely a fox, but publishers control this industry, they have the talent, and content, as long as they do their job, by protecting and nurturing that talent and live alongside high street bookshops in relative harmony [the book trade can weather the storm]... but do not believe that [Amazon is] anything other than a fox, and don't let them in the coop."

"Amazon is a commercially driven organization of extreme vigor, and everything indicates that that internal dynamic within its nature... Amazon is definitely a fox, but publishers control this industry, they have the talent, and content, as long as they do their job, by protecting and nurturing that talent and live alongside high street bookshops in relative harmony [the book trade can weather the storm]... but do not believe that [Amazon is] anything other than a fox, and don't let them in the coop."

SHELFAWARENESS.0213.S4.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

Nominees have been unveiled for the 2019 Pannell Award, which is co-sponsored by the

Nominees have been unveiled for the 2019 Pannell Award, which is co-sponsored by the

"There's been a real renaissance when it comes to independent bookstores," owner Stephanie Gordon told SMN. "People are moving away from big box retailers and are looking for localism. It's a romantic idea to spend a rainy day in a bookstore with a glass of wine."

"There's been a real renaissance when it comes to independent bookstores," owner Stephanie Gordon told SMN. "People are moving away from big box retailers and are looking for localism. It's a romantic idea to spend a rainy day in a bookstore with a glass of wine." When it came to opening Rough Draft, Gordon actually had to work with the city council and local government to change the town's liquor laws. Up until very recently, the town essentially only allowed for restaurants to serve alcohol. Gordon and her husband helped establish a new category for taverns or bars, which did not previously exist in McDonough.

When it came to opening Rough Draft, Gordon actually had to work with the city council and local government to change the town's liquor laws. Up until very recently, the town essentially only allowed for restaurants to serve alcohol. Gordon and her husband helped establish a new category for taverns or bars, which did not previously exist in McDonough.SHELFAWARENESS.0213.T3.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

At

At  Todd Dickinson, co-owner of

Todd Dickinson, co-owner of  In Manzanita, Ore.,

In Manzanita, Ore.,  Last week the

Last week the

MIT Press has begun handling worldwide sales, marketing and fulfillment for

MIT Press has begun handling worldwide sales, marketing and fulfillment for  Living and Dying on the Factory Floor: From the Outside In and the Inside Out

Living and Dying on the Factory Floor: From the Outside In and the Inside Out

Book you're an evangelist for:

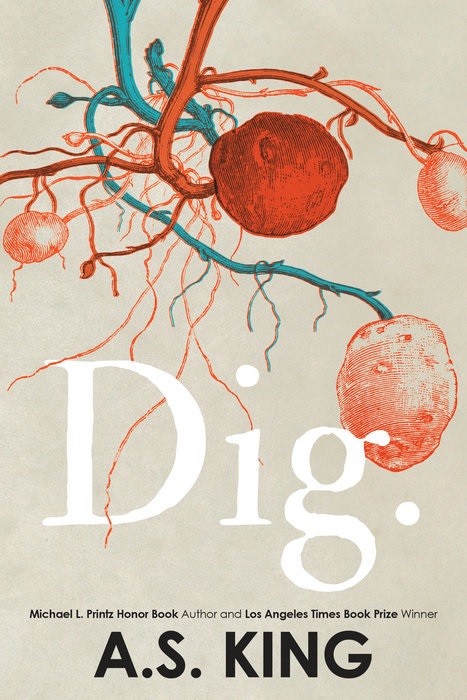

Book you're an evangelist for: For 200 years, Gottfried Hemmings's family owned a Pennsylvania potato farm. By the time Gottfried's fifth child was born, the farm had been divided up among him and his siblings. Gottfried sold his portion to developers. He and his wife, Marla, now have "more than ten million dollars in the bank"--which they refuse to share with their grown children or grandchildren because they want them to be "independent."

For 200 years, Gottfried Hemmings's family owned a Pennsylvania potato farm. By the time Gottfried's fifth child was born, the farm had been divided up among him and his siblings. Gottfried sold his portion to developers. He and his wife, Marla, now have "more than ten million dollars in the bank"--which they refuse to share with their grown children or grandchildren because they want them to be "independent."