|

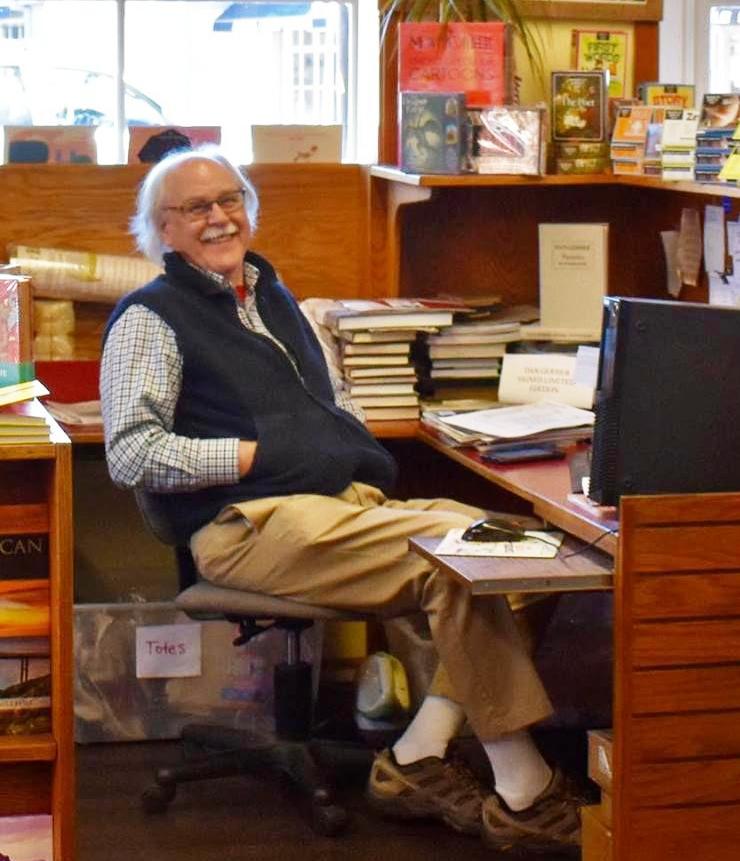

| photo: Staci Michelle Williams |

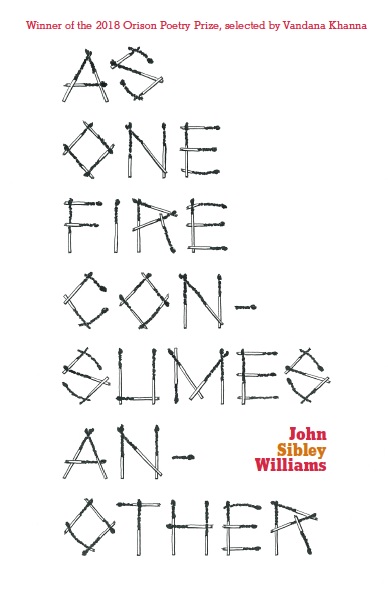

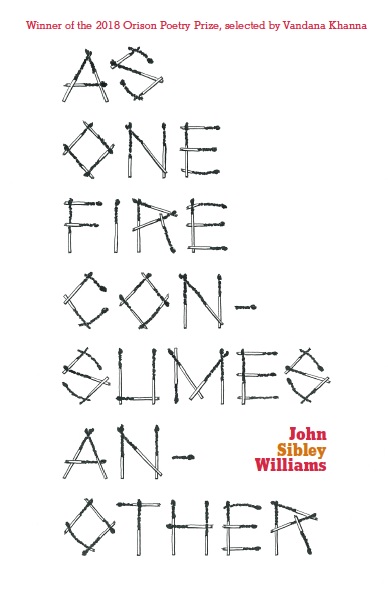

John Sibley Williams is the author of As One Fire Consumes Another: Poems, just out from Orison Books, selected by Vandana Khanna for the Orison Poetry Prize. Another collection, Skin Memory, was chosen by Kwame Dawes for the Backwaters Prize and will be published by the Backwaters Press later this year. Williams is also the author of Disinheritance and Controlled Hallucinations. A 19-time Pushcart nominee, Williams has won the Philip Booth Award, the American Literary Review poetry contest and the Phyllis Smart-Young Prize, among others. He serves as editor of the Inflectionist Review, works as a literary agent and lives in Portland, Ore., with his partner and twin toddlers.

On your nightstand now:

As I tend to read multiple poetry collections simultaneously, bouncing back and forth between them to keep things fresh and surprising, my nightstand is always a bit crowded. I'm about to finish Admission Requirements by Phoebe Wang, an intimate collection of memoirish poems that speak to Wang's distinctive experience as a Canadian citizen with Chinese heritage. I'm also reading Cutting the Wire: Photographs and Poetry from the US-Mexico Border, a powerful cultural collaboration between photographer Bruce Berman and poets Ray Gonzalez and Lawrence Welsh. And awaiting my attention is Monica Berlin's second collection, Nostalgia for a World Where We Can Live. I love her long, fluid lines and landscape-inspired voice.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Although I don't have any direct memories from toddlerhood, I'm told no one could yank Shel Silverstein's The Giving Tree from my hungry little hands. Now that I'm a parent, I can understand why. I choke up each time I read it to my little ones. In middle school I read armloads of horror novels, then moved to Franz Kafka, Albert Camus and Milan Kundera in high school. Looking back, I think the mystical strangeness of these authors mirrored my adolescent uncertainty and restlessness. Many of their characters are lost, be it within a heartless bureaucratic system or their own conflicted hearts. How better to describe one's teen years?

Your top five authors:

Paul Celan was able to make language pop and sizzle like bacon deep frying in a skillet, all while remaining imagistic and surreal. I never knew where I stood with him, nor him with me, and that adds to his strange linguistic power. Octavio Paz remarkably spoke both to fundamental human truths and a specific cultural zeitgeist through structural experimentation and heartbreaking prosody. Carl Phillips may be my favorite contemporary poet. Each new book peels back another layer of soul, and he consistently inspires me. I'll have to add Franz Kafka here, too, if for no other reason than I've read his oeuvre three or four times. And I'll never stop rereading Julio Cortázar's mind-altering novels and short stories.

Book you've faked reading:

This may sound sacrilegious in the poetry community, but I've never quite read Leaves of Grass in its entirety. I know, I know. And although I've relished Dostoyevsky's immense novels, I haven't touched any of Tolstoy's. I know, I know.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Although new to our poetry world, Marcelo Hernandez Castillo's debut, Cenzontle (BOA Editions, 2018), is one of the most remarkable collections of intimate, broken, beautiful poetry I've ever read. Comparable to another of my contemporary favorites, Ocean Vuong, Castillo carries the world on his young shoulders and somehow, perhaps magically, the world remains there, lifted and less heavy.

Book you've bought for the cover:

A few years back, having digested the novels of Halldór Laxness and Sjón, I was on the hunt for more Icelandic fiction. The cover of Kristin Omarsdottir's Children in Reindeer Woods seduced me into purchasing it without reading its synopsis. Its sharp angles, inimitable font and artificially bright colors captured my attention, and the marionette strings from which the title hangs implied restraint of willpower and manipulation from greater forces.

Book you hid from your parents:

That's a tough one. My parents were rather open-minded about my reading choices, even at a young age. However, I remember hiding James Baldwin's Giovanni's Room deep in my high school locker after a few peers bullied me for reading it.

Book that changed your life:

One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest by Ken Kesey awoke something deep within me when I first read it. I must have been around 15 or so. In less than 300 pages--a few days of reading for a hungry teenager--the various prisons we build around ourselves to keep the world out and those the world squeeze us into for safe keeping fused. Cages are cages, and I realized many of my own were self-made.

Favorite line from a book:

An impossible task to name a single line, but Pablo Neruda's "My soul is an empty carousel at sunset" speaks to the beautiful, dark contradiction of the human condition in a way few lines of poetry or prose can match.

Five books you'll never part with:

Although there are hundreds of books I can't imagine my creative life without, the five that immediately spring to mind are One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, All the Names by Jose Saramago, Night Sky with Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong, City of Rivers by Zubair Ahmed and Carl Phillips's fantastic book on writing The Art of Daring: Risk, Restlessness, Imagination. Each of these works reach deep into my heart. Each of them hurt me a little. Each push me to climb and climb from myself, hopefully toward greater literary heights.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

I don't know how many times I've read Man's Search for Meaning by psychologist and Holocaust survivor Viktor E. Frankl. A dozen? With each reading, I find new questions to ask myself, the world and my place in the world. This seminal work frames much of my understanding of human nature, and I don't think a day goes by in which its insights aren't validated in my daily life. But there was nothing like that first time reading it. It was as if the earth shifted. It was as if I'd stepped from a dark tunnel into an early morning summer sun. I think my eyes are still adjusting to its light.

Invaluable lesson from a book:

Before reading Kevin Young's staggering collection The Book of Hours, I had kept my family life removed from my poetry. For some reason, I felt the two should remain distinct entities. Family was hands-off material. Perhaps I was terrified of inviting readers into my home. That kind of intimacy makes a writer feel naked. But Young's book, so abundant in rich poems about his wife and child and pregnancy and fatherly fears, proved to me that one can write from the heart without losing the universality of language poems require to reach off the page and haunt a reader.

IPC.0204.S3.INDIEPRESSMONTHCONTEST.gif)

"The 'For Sale' sign has come down!"

"The 'For Sale' sign has come down!"

James Patterson has pledged $1.25 million to save classroom libraries in the fifth installment of his

James Patterson has pledged $1.25 million to save classroom libraries in the fifth installment of his

IPC.0211.T4.INDIEPRESSMONTH.gif)

The Book Industry Charitable Foundation has kicked off its annual spring fundraising drive. The

The Book Industry Charitable Foundation has kicked off its annual spring fundraising drive. The

"

" The Girl He Used to Know: A Novel

The Girl He Used to Know: A Novel

Book you're an evangelist for:

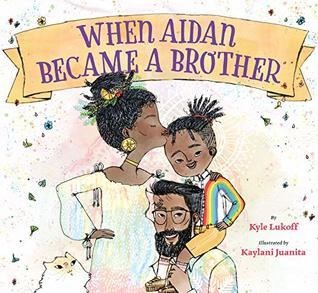

Book you're an evangelist for: "When Aidan was born, everyone thought he was a girl." But his name, his room, his clothes just didn't fit. Aidan realized "he was really another kind of boy. It was hard to tell his parents what he knew about himself, it was even harder not to": Aidan is transgender. With the help of other families with transgender children, Aidan's family figured things out. Now his parents have announced they are having another child, making Aidan a soon-to-be big brother.

"When Aidan was born, everyone thought he was a girl." But his name, his room, his clothes just didn't fit. Aidan realized "he was really another kind of boy. It was hard to tell his parents what he knew about himself, it was even harder not to": Aidan is transgender. With the help of other families with transgender children, Aidan's family figured things out. Now his parents have announced they are having another child, making Aidan a soon-to-be big brother.