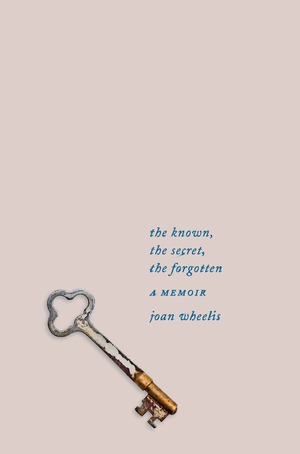

The penultimate chapter of Joan Wheelis's memoir, The Known, the Secret, the Forgotten,is a short vignette called "The Pin." Going through her mother's things after her death, Wheelis finds an old note to her mother from her father, who has also died. It reads, "A stone, a ----, a door." There are two small holes in place of the missing word. Wheelis recognizes the line from Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel; the missing word is "leaf."She is struck by a long-ago memory of her mother showing her a leaf-shaped pin, a gift from her father. Wheelis hasn't seen the pin in 50 years. Later, after dreaming about it, she finds it in a box marked "Important."

The penultimate chapter of Joan Wheelis's memoir, The Known, the Secret, the Forgotten,is a short vignette called "The Pin." Going through her mother's things after her death, Wheelis finds an old note to her mother from her father, who has also died. It reads, "A stone, a ----, a door." There are two small holes in place of the missing word. Wheelis recognizes the line from Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel; the missing word is "leaf."She is struck by a long-ago memory of her mother showing her a leaf-shaped pin, a gift from her father. Wheelis hasn't seen the pin in 50 years. Later, after dreaming about it, she finds it in a box marked "Important."

"I bring it to my father's note and slide the clasp through the two little holes," she writes. "It fits perfectly."

"The Pin" is emblematic of Wheelis's book, beginning with the rhythmic similarity "a stone, a leaf, a door" bears to the book's title. Like the phrase, the book is brief but lyrically evocative. And, like the note, its middle is also missing--or, at least, not immediately perceptible.

Thisis a memoir of Wheelis's unusual, privileged childhood growing up as the only child of distinguished psychoanalysts in midcentury San Francisco. Told from a vantage point 50-plus years in the future, Wheelis's recollections have a dreamlike quality--misty, distant, but shot through with immediate, vivid details and symbolic suggestion. Her narrative favors impressions and themes over chronology, shifting from scene to scene, memory to memory, without concern for sequential plotting. One moment she's six years old and puzzling over the "endlessly intriguing" mystery of her parents' work, which they both conducted from Wheelis's home; the next, she's having an existential conversation with her elderly father as they watch the Blue Angel jets fly over the Presidio.

Wheelis only briefly alludes to her life in between those early years and the near-present--becoming a psychoanalyst herself, having a son, her husband leaving her. The absence of most of her life from this narrative suggests a strong link between her earliest memories and who she is today.

The link--or the pin, if you will--between the two time periods is her parents' legacy, particularly her father's. Wheelis paints him as an exacting, disciplined man of rigorous intellect and scrupulousness who nonetheless imparted her with a certain zeal for living. The paradoxical remoteness and intimacy of their relationship, and her memory of how it evolved over time, is the cornerstone of the book. Fittingly, Wheelis later describes memory as "the rich layering of time and experience. Built like a stone wall"--one that, eventually, like all things, wears down and falls away. --Hannah Calkins, writer and editor in Washington, D.C.

Shelf Talker: Poetic and reflective, this spare but evocative memoir is a lovely meditation on time, memory and generational legacies.

Prior to opening

Prior to opening  Herron officially began looking for retail space in late December, and on March 15, Mil Mundos was open for business. The roughly 500-square-foot store has an inventory evenly divided between Spanish- and English-language titles, with a focus on celebrating black and Latinx culture. And while Herron and her team, which consists of three other booksellers, sell some used books, the majority of the inventory is made up of new titles.

Herron officially began looking for retail space in late December, and on March 15, Mil Mundos was open for business. The roughly 500-square-foot store has an inventory evenly divided between Spanish- and English-language titles, with a focus on celebrating black and Latinx culture. And while Herron and her team, which consists of three other booksellers, sell some used books, the majority of the inventory is made up of new titles. As for nonbook items, Herron said Mil Mundos carries some arts and crafts items, educational toys for children and a selection of candles. She and her team are currently waiting on stock for a tarot deck about which they are very excited, and are continually looking for new local vendors. Mil Mundos also has a small coffee bar. The store sells coffee, tea and guava pastries, which Herron and company purchase from a local Colombian bakery called Son de Cali. Added Herron: "And at times when it's not too busy, we also brew up Cuban cafecitos as well."

As for nonbook items, Herron said Mil Mundos carries some arts and crafts items, educational toys for children and a selection of candles. She and her team are currently waiting on stock for a tarot deck about which they are very excited, and are continually looking for new local vendors. Mil Mundos also has a small coffee bar. The store sells coffee, tea and guava pastries, which Herron and company purchase from a local Colombian bakery called Son de Cali. Added Herron: "And at times when it's not too busy, we also brew up Cuban cafecitos as well."

More than half of the $25,000 goal has been met through the "

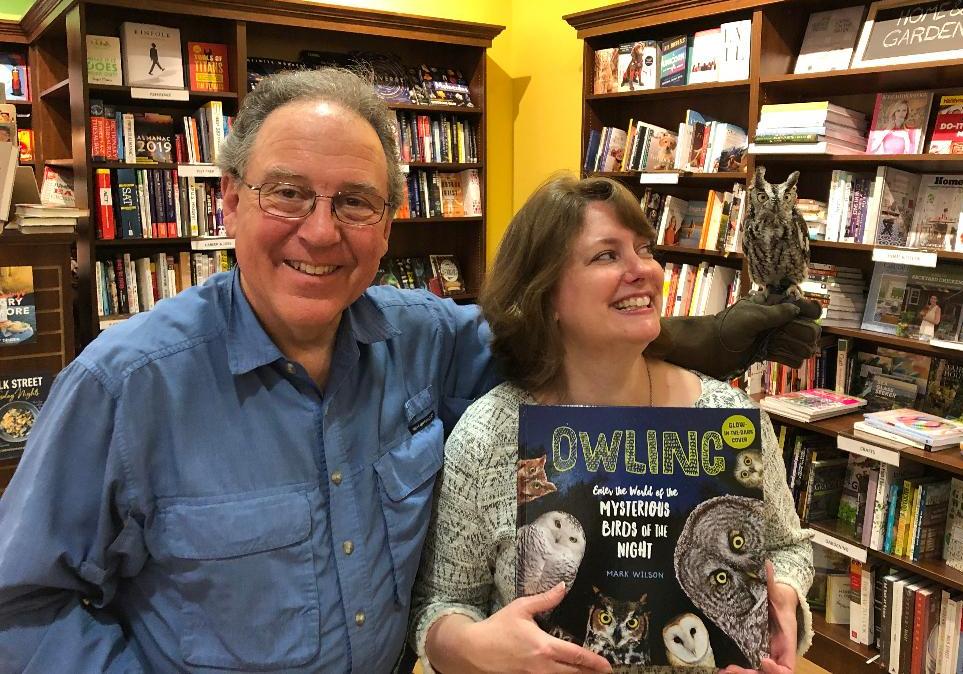

More than half of the $25,000 goal has been met through the " Melissa Posten, children's buyer and event coordinator for the

Melissa Posten, children's buyer and event coordinator for the

Whitelam Books

Whitelam Books The Little Guys

The Little Guys The penultimate chapter of Joan Wheelis's memoir, The Known, the Secret, the Forgotten,is a short vignette called "The Pin." Going through her mother's things after her death, Wheelis finds an old note to her mother from her father, who has also died. It reads, "A stone, a ----, a door." There are two small holes in place of the missing word. Wheelis recognizes the line from Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel; the missing word is "leaf."She is struck by a long-ago memory of her mother showing her a leaf-shaped pin, a gift from her father. Wheelis hasn't seen the pin in 50 years. Later, after dreaming about it, she finds it in a box marked "Important."

The penultimate chapter of Joan Wheelis's memoir, The Known, the Secret, the Forgotten,is a short vignette called "The Pin." Going through her mother's things after her death, Wheelis finds an old note to her mother from her father, who has also died. It reads, "A stone, a ----, a door." There are two small holes in place of the missing word. Wheelis recognizes the line from Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel; the missing word is "leaf."She is struck by a long-ago memory of her mother showing her a leaf-shaped pin, a gift from her father. Wheelis hasn't seen the pin in 50 years. Later, after dreaming about it, she finds it in a box marked "Important."