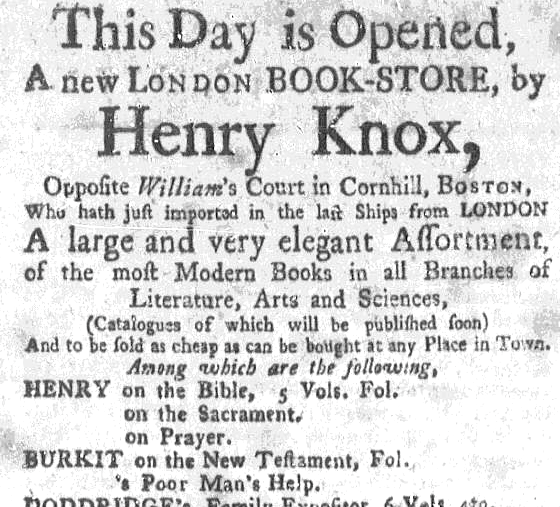

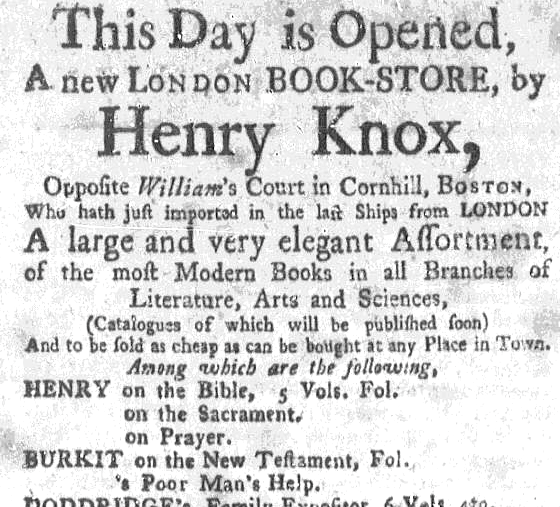

In anticipation of Independent Bookstore Day tomorrow, I've been thinking about the bookselling life of Henry Knox, who was born in Boston (1750) and self-educated. According to David McCullough's 1776, he became a bookseller as a young man, and in 1771 opened his own establishment, the London Book-Store, offering "a large and very elegant assortment" of the latest books and magazines.

In anticipation of Independent Bookstore Day tomorrow, I've been thinking about the bookselling life of Henry Knox, who was born in Boston (1750) and self-educated. According to David McCullough's 1776, he became a bookseller as a young man, and in 1771 opened his own establishment, the London Book-Store, offering "a large and very elegant assortment" of the latest books and magazines.

"In the notices he placed in the Boston Gazette, the name Henry Knox always appeared in larger type than the name of the store," McCullough writes. The Gazette also noted that his stock included "the most modern books in all branches of Literature, Arts and Sciences."

|

Henry Knox

(portrait by Gilbert Stuart, 1806) |

In his introduction to The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox, editor Phillip Hamilton portrays a bookshop environment that sounds quite contemporary, noting that Knox's store "thrived under his direction, largely due to his personality.... Knowledgeable about literature, history, and politics, he loved engaging in conversations and easily struck up friendships.... Ambitious, eager to rise above the hardships of his youth, and supremely confident in himself, Knox always engaged customers in similar discussions."

The bookshop also prospered because of his business mind, including an ability to master commercial and financial details. Hamilton writes that Knox's surviving wastebook (a financial ledger in which he wrote daily transactions) and correspondence with customers "reveal the care with which he managed the overall operation." In addition, his ties to London gave him "regular access to thousands of recently published books and magazines, as well as to the latest news regarding literary trends, social fads, and political intelligence."

Now let's talk about location, location, location. The London Book-Store was on Cornhill near the center of Boston, which "further contributed to its success," Hamilton notes. "Before 1771, the city already supported 15 book and print shops, due to the fact that its 16,000 residents were mostly literate, because of the Congregationalist's belief that all people should read the Bible for themselves."

Now let's talk about location, location, location. The London Book-Store was on Cornhill near the center of Boston, which "further contributed to its success," Hamilton notes. "Before 1771, the city already supported 15 book and print shops, due to the fact that its 16,000 residents were mostly literate, because of the Congregationalist's belief that all people should read the Bible for themselves."

Because it was located less than a block from the Massachusetts Town House, "not only Whigs and members of the Sons of Liberty frequented the bookstore, but Crown officials, American Tories, and British officers also stopped by on a daily basis," Hamilton observes. Prominent Boston historian Harrison Gray Otis later characterized the store as "one of great display and attraction for young and old, and a fashionable morning lounge."

McCullough adds that the clientele also included troublemakers like John Adams, a frequent patron who remembered Knox as a youth "of pleasing manners and inquisitive turn of mind"; as well as Nathanael Greene, "who not only shared Knox's love of books, but also an interest in 'the military art,' and it was thus, on the eve of war, that an important friendship had commenced."

Booksellers' lives are deeply influenced by their patrons. Sometimes the relationships become something more. Knox fell in love with one of his customers, Lucy Flucker, whom he eventually married despite objections from her Loyalist father, a royal secretary of the province.

Lucy "probably entered Knox's establishment for the first time in 1772," Hamilton writes. "Though only 16 years old, she already possessed a formidable personality. Her correspondence reveals that, even as a teenager, she had a quick mind, strong opinions, and deeply felt emotions, which she rarely hesitated to share with others.... she developed an exceptionally strong streak of independence. The historical record is silent regarding Lucy's education, but it was clearly substantial. Trained to write in the italianate hand, she learned to express her thoughts and sentiments with precision and vigor. Like her future husband, she developed a love of reading and particularly enjoyed conversations about literature and other social topics."

I particularly like Hamilton's description of their bookish courtship ritual and suspect more than a few booksellers can relate to the recollection that "at some point in 1773, they started to exchange furtive glances inside Knox's bookstore and then had flirtatious tête-à-têtes at a nearby coffeehouse."

Henry and Lucy married in 1774, but any future bookselling life together was quickly shattered. By 1775, as "the 'carnage and bloodshed' Henry feared approached, he struggled to keep the bookstore open," Hamilton writes. The last Boston Gazette advertisement for the London Book-Store featured a pamphlet titled The Farmer refuted:.. intended as a further vindication of the Congress by a man who would soon become his comrade-in-arms, Alexander Hamilton.

Knox went on to become a Revolutionary War hero, playing an instrumental role when he conceived and executed the daring relocation of more than 50 captured British cannons overland from Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain to Boston--an arduous winter journey of nearly 300 miles--to help end the British siege of the city. He eventually rose to the rank of Major General, and later served in President George Washington's cabinet.

The bookshop, vandalized during the war, did not ultimately survive. As bookselling lives go, however, Henry's was a particularly intense, exciting and, yes, independent one, in every sense of the word. So I'll raise a glass to his memory tomorrow as I celebrate another Independent Bookstore Day.

Tomorrow is the fifth annual Independent Bookstore Day, which is being celebrated across the country by more than 500 bookstores. Please send reports and pictures at news@shelf-awareness.com for our extensive coverage in Monday morning's issue. We wish all participants a busy, successful day.

Tomorrow is the fifth annual Independent Bookstore Day, which is being celebrated across the country by more than 500 bookstores. Please send reports and pictures at news@shelf-awareness.com for our extensive coverage in Monday morning's issue. We wish all participants a busy, successful day.

In the first quarter ended March 31, net sales at Amazon rose 17%, to $59.7 billion, and net income more than doubled, to $3.6 billion compared to $1.6 billion in the same period a year earlier. The net sales gain, the lowest in a quarter in four years, was consistent with analysts' expectations, while the profit gain was more than double expectations.

In the first quarter ended March 31, net sales at Amazon rose 17%, to $59.7 billion, and net income more than doubled, to $3.6 billion compared to $1.6 billion in the same period a year earlier. The net sales gain, the lowest in a quarter in four years, was consistent with analysts' expectations, while the profit gain was more than double expectations.

After more than four years of planning, owner Noëlle Santos is set to open

After more than four years of planning, owner Noëlle Santos is set to open

The Publishing Triangle Awards, honoring the best LGBTQ books of 2018, were presented last night at the New School in New York City. Pictured: (l.-r.) Carol Rosenfeld, chair of the Publishing Triangle; Jaime Manrique, recipient of the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement; and Trent Duffy, awards chair and treasurer of the Publishing Triangle. WORD Bookstore sold books at the event. See the complete list of Publishing Triangle Award winners below. (photo: Tracy Ketcher)

The Publishing Triangle Awards, honoring the best LGBTQ books of 2018, were presented last night at the New School in New York City. Pictured: (l.-r.) Carol Rosenfeld, chair of the Publishing Triangle; Jaime Manrique, recipient of the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement; and Trent Duffy, awards chair and treasurer of the Publishing Triangle. WORD Bookstore sold books at the event. See the complete list of Publishing Triangle Award winners below. (photo: Tracy Ketcher) Fabled Bookshop & Cafe

Fabled Bookshop & Cafe Mysterious Galaxy

Mysterious Galaxy Ruffage: A Practical Guide to Vegetables

Ruffage: A Practical Guide to Vegetables Here are the winners of the 2019

Here are the winners of the 2019  Winners of the

Winners of the

World Fantasy Award-winner Guy Gavriel Kay (Ysabel) returns to the world of

World Fantasy Award-winner Guy Gavriel Kay (Ysabel) returns to the world of

Now let's talk about location, location, location. The London Book-Store was on Cornhill near the center of Boston, which "further contributed to its success," Hamilton notes. "Before 1771, the city already supported 15 book and print shops, due to the fact that its 16,000 residents were mostly literate, because of the Congregationalist's belief that all people should read the Bible for themselves."

Now let's talk about location, location, location. The London Book-Store was on Cornhill near the center of Boston, which "further contributed to its success," Hamilton notes. "Before 1771, the city already supported 15 book and print shops, due to the fact that its 16,000 residents were mostly literate, because of the Congregationalist's belief that all people should read the Bible for themselves."