Barbara Probst Solomon, an American memoirist and essayist "known for documenting life in Spain during and after the regime of General Francisco Franco," died September 1, the New York Times reported. She was 90. Solomon was renowned in particular for her 1972 memoir, Arriving Where We Started, "which chronicled her youthful involvement with the anti-Franco resistance movement, including her naïvely brazen rescue of two resistance members from a Spanish labor camp."

At 19, Barbara Probst persuaded her mother to escort her to Paris and let her live there on her own. During the voyage over, they met the mother and sister of a would-be writer, Norman Mailer, who was in Paris working on his first novel, which would become The Naked and the Dead. He became a friend, as did his sister, also named Barbara.

In Arriving Where We Started, Solomon wrote: "Norman approached his sister Barbara and me, and in a somewhat offhand, slightly conspiratorial tone asked the two of us how we would like to uh, sort of, spring a few people from a Franco jail in Spain.... Neither Barbara nor I had any true sense of what we were getting into. As for danger or consequences, life was to be led like a book; in books good people lived dangerously." The Times noted: "Against all odds, the scheme worked."

A novelist and a translator from the Spanish, Solomon was also a widely-published essayist. Her other books include two novels, The Beat of Life (1960) and Smart Hearts in the City (1992); a second memoir, Short Flights (1983), and the essay collection Horse-Trading and Ecstasy (1989).

Solomon taught at Sarah Lawrence College and elsewhere. She was a founder and the editor in chief of The Reading Room, a literary journal. For many years, she was the U.S. cultural correspondent for the Spanish newspaper El País. In 2008, she was awarded the Francisco Cerecedo Prize by the Association of European Journalists in Spain, the first North American to be so honored. In an interview after she won the prize, Solomon "sought to play down the significance of her laurels in the context of the historical struggles about which she wrote," the Times noted.

"You don't plan these things, you know," she said. "One thing I learned was that the butcher, baker and candlestick maker who're thrown in jail don't enter history--they're not writers. But writers can become known. History's not fair."

Etaf Rum, whose debut novel, A Woman Is No Man, was published by Harper in March, is

Etaf Rum, whose debut novel, A Woman Is No Man, was published by Harper in March, is

Authors Kwame Alexander (l.) and Jason Reynolds take a break following a TV interview with BBC Scotland during the Edinburgh International Book Festival. At the festival, they participated in a panel with Sarah Crossan called "Writing Rhythm," during which they discussed the growing popularity of verse novels and how to tell diverse, dynamic stories.

Authors Kwame Alexander (l.) and Jason Reynolds take a break following a TV interview with BBC Scotland during the Edinburgh International Book Festival. At the festival, they participated in a panel with Sarah Crossan called "Writing Rhythm," during which they discussed the growing popularity of verse novels and how to tell diverse, dynamic stories. Posted on Facebook yesterday afternoon by

Posted on Facebook yesterday afternoon by  Congratulations to

Congratulations to  Serpent and Dove

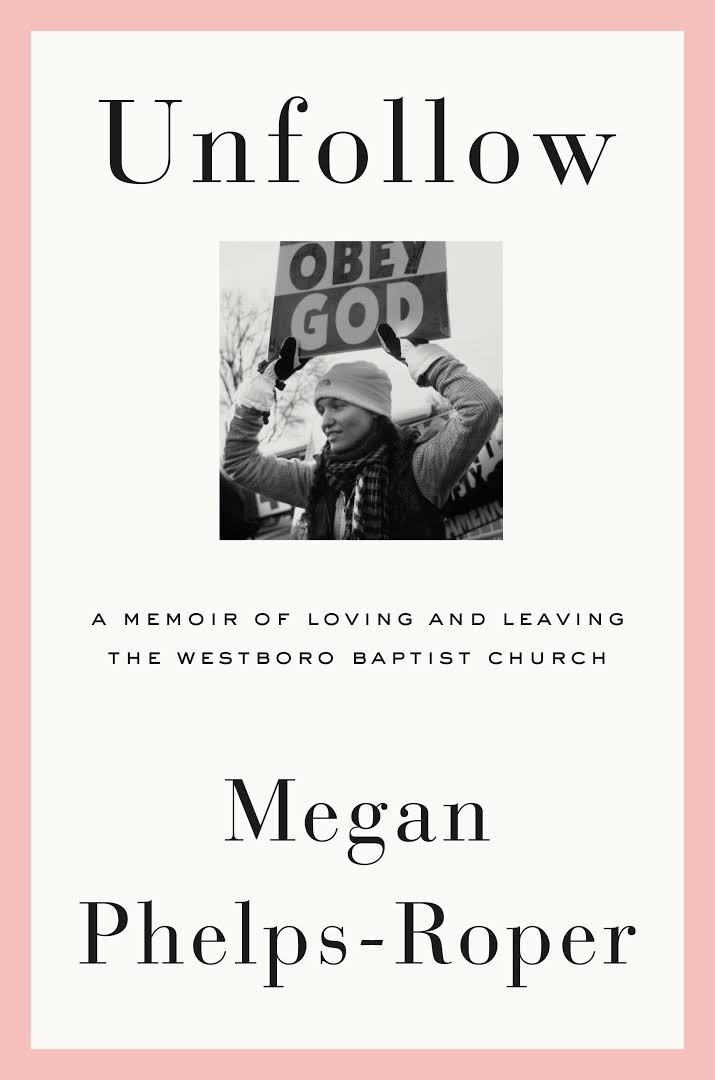

Serpent and Dove Megan Phelps-Roper grew up as a cherished daughter of Topeka's Westboro Baptist Church, notorious for its inflammatory rhetoric and protest signs (most notably "God Hates Fags"). The third of 11 children, she joined her first picket line at age five, and spent her childhood and adolescence fervently spreading--and believing in the rightness of--Westboro's message. But in her 20s, her engagement with Westboro's critics on social media made her wonder if the church had a monopoly on rightness.

Megan Phelps-Roper grew up as a cherished daughter of Topeka's Westboro Baptist Church, notorious for its inflammatory rhetoric and protest signs (most notably "God Hates Fags"). The third of 11 children, she joined her first picket line at age five, and spent her childhood and adolescence fervently spreading--and believing in the rightness of--Westboro's message. But in her 20s, her engagement with Westboro's critics on social media made her wonder if the church had a monopoly on rightness.