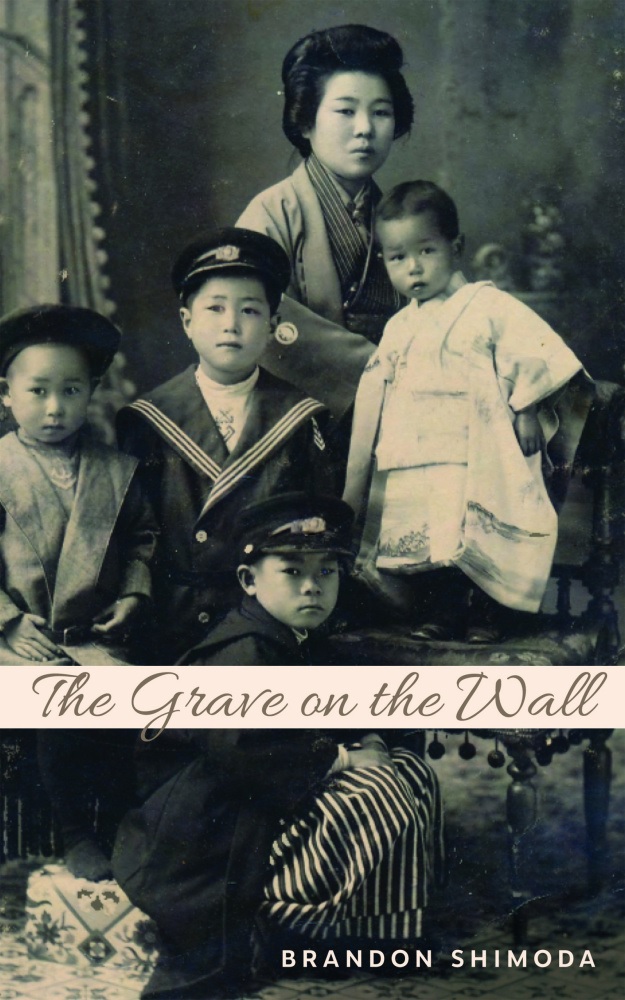

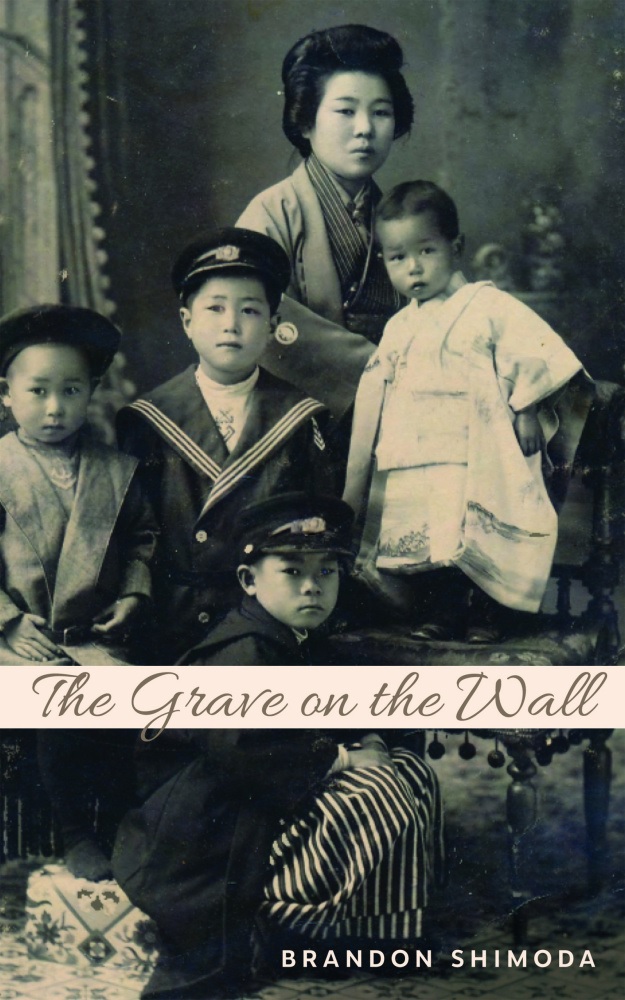

Brandon Shimoda's first book of nonfiction, an ancestral memoir called The Grave on the Wall, was just published by City Lights Books. He is also the author of six books of poetry, most recently The Desert (The Song Cave) and Evening Oracle (Letter Machine Editions), which received the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America. He is writing a book on the ongoing afterlife/ruins of Japanese American incarceration, notes and sketches from which have been published by the Asian American Literary Review, Densho, Hyperallergic, the Margins, the Massachusetts Review and the New Inquiry. He tweets @brandonshimoda.

Brandon Shimoda's first book of nonfiction, an ancestral memoir called The Grave on the Wall, was just published by City Lights Books. He is also the author of six books of poetry, most recently The Desert (The Song Cave) and Evening Oracle (Letter Machine Editions), which received the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America. He is writing a book on the ongoing afterlife/ruins of Japanese American incarceration, notes and sketches from which have been published by the Asian American Literary Review, Densho, Hyperallergic, the Margins, the Massachusetts Review and the New Inquiry. He tweets @brandonshimoda.

On your nightstand now:

A sound machine and four books I read to my (11-month-old) daughter every night: Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña and illustrated by Christian Robinson; Peach Boy by Florence Sakade and illustrated by Yoshisuke Kurosaki (her favorite story is "The Magic Teakettle"); Issun Boshi by Icinori; and Hortense and the Shadow by Natalia and Lauren O'Hara.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Penny's computer book. (Penny being Inspector Gadget's niece.) Her computer book was basically a computer disguised as a book, which was mind-blowing, to me, in the 1980s. Penny could look up anything. She could video chat. Hack into other computers. Her computer book had a digital map. Even a laser! She always carried it with her. I wanted it. Or I thought I did. Her computer book eventually manifested in real life in the form of iPhones, iPads, etc., but Penny's computer book possessed a surreptitiousness reality could only diminish. Also: Encyclopedia Britannica (unknown edition, also 1980s). A salesman came to our door. We invited him in. He was old and white, and looked and smelled like he might have written the encyclopedias himself. When my mother told me that my Japanese teacher's husband taught himself English by reading the dictionary cover-to-cover, I decided I was going to read the entire Encyclopedia Britannica cover-to-cover. To teach myself what? I did not get very far. But I did spend much of my childhood opening up the many-volume encyclopedia at random and reading whatever appeared.

Your top five authors:

James Baldwin, Yasunari Kawabata, Etel Adnan, Simone Weil (or maybe Malika Mokeddem), Marguerite Duras (my dream is to write a book about the afterlife of Japanese American incarceration in the style of Duras's The Lover.)

Book you've faked reading:

I became a reader, I think, by faking reading. I don't know when, or if, the transition was made between faking reading and not faking reading.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Every time I see a used copy of Kawabata's Palm-of-the-Hand Stories (translated from the Japanese by Lane Dunlop and J. Martin Holman), I buy it, because I want to be prepared for the moment when someone is visiting and I tell them how much I love it, so that I can pull it, like magic, out of my sleeve.

Book you've bought for the cover:

Book you've bought for the cover:

Most of my favorite books have unremarkable covers. (Most books I read I check out from the university library, and often have no cover at all.) When I was in high school, I bought a book at the Salvation Army for the cover. The book was thin, green, with a contour drawing, on the cover, of a flower, a dandelion or daisy. It took me a minute to realize the book's title was spelled out in the flower's petals: The Double Dream of Spring. It was my first encounter with John Ashbery, and one of my first legitimate encounters with contemporary poetry, which, at the time, I hated, with a hatred that was confirmed by what I found in The Double Dream of Spring, but that transformed, over time, into a problem, then a commitment, then, as it is now: an orientation and a way of perceiving.

Book you hid from your parents:

My parents hid books from me.

Book that changed your life:

There are a few books I read every year, partly to see how, a year later, I have changed, and to affirm that my life has changed. (Although I read them mostly because I love them.) Etel Adnan's Sitt Marie Rose (translated from the French by Georgina Kleege), James Baldwin's No Name in the Street, Dot Devota's And the Girls Worried Terribly and The Division of Labor, Bhanu Kapil's Ban en Banlieue and Schizophrene, Kawabata's Palm-of-the-Hand Stories and Lynn Xu's Debts & Lessons.

Favorite line from a book:

My favorite line is lines: every book I've read has one. And they change. Depending on when I'm reading, or where. The weather, time of day, if I'm reading while walking (outside). These lines, however, from one of my favorite books of poetry--The Division of Labor by Dot Devota--suggest, in part, how the relationship that forms, sometimes fleetingly, between myself and a line or sentence or stanza, is, in its moment, absolutely consuming, and at the expense of everything else:

It wasn't important enough

to make me want to leave my book

Five books you'll never part with:

This question makes me feel like I am being forced to part with everything--in my life--that is not one of these five books, although if I was actually being forced to part with everything in my life, I think I might be able to part with these five books as well, not because I could so easily live without them, but because I cannot, because I do not--even when I am not with them--live without them:

Yasunari Kawabata, Palm-of-the-Hand Stories (tr. Lane Dunlop & J. Martin Holman)

James Baldwin, Collected Essays

Man'yoshu: One Thousand Poems (tr. Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkokai)

Etel Adnan, To look at the sea is to become what one is (Disclaimer: I edited this book with Thom Donovan. Partly what I mean by including this book among my five is: all Etel's books)

The fifth book is a book that exists, in my mind, as a single book, but is comprised of the books written by my closest friends, including books that have not yet been published, are in-progress, or are not even books, including (among many): Dot Devota's MW: A Field Guide to the Midwest, Youna Kwak's The Second Life, Elisabeth Benjamin'sDogs, Molly McDonald'sAt the Moosehorn, Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman's MELEKHMELEKHMELEKHMELEKH: An Assimilation.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Most of the books I have read I want to read again. It feels strange to admit that so many of the books I love I will never read again, either because I will forget or I won't live long enough. I have a bad memory for what I have read. Not the books themselves (I keep a list), but their lines, sentences, paragraphs. My memory of what I have read is the same as my memory of what I have experienced: fragmented, fogged, composed of auras, impressions. This makes it possible, when reading a book I have already read, to be reading it as if for the first time.

Coinciding with its 125th anniversary in November,

Coinciding with its 125th anniversary in November,

Baen Books and RBmedia are publishing more than 170 of Baen's titles as audiobooks over the next three years. Baen is one of the major independent publishers of science fiction and fantasy books while RBmedia specializes in publishing sci-fi and fantasy audiobooks.

Baen Books and RBmedia are publishing more than 170 of Baen's titles as audiobooks over the next three years. Baen is one of the major independent publishers of science fiction and fantasy books while RBmedia specializes in publishing sci-fi and fantasy audiobooks.

The Last Train to London

The Last Train to London

Book you've bought for the cover:

Book you've bought for the cover: Fresh off her Caldecott Honor win for

Fresh off her Caldecott Honor win for

City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert, read by Blair Brown (Penguin Audio) Blair Brown delivers a superb narration of Elizabeth Gilbert's novel, which features the recollections of a 95-year-old New York seamstress who came of age during World War II. Brown's straightforward, charming depiction illuminates the vivacious young woman the wistful elderly narrator remembers, and her conversational pacing creates vibrant pictures for the listener. The action is set in 1940, after Vivian dropped out of Vassar and moved to Manhattan to help her aunt run a decrepit theater company. She also created stunning costumes for the company, including a middle-aged British actress memorably rendered by Brown.

City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert, read by Blair Brown (Penguin Audio) Blair Brown delivers a superb narration of Elizabeth Gilbert's novel, which features the recollections of a 95-year-old New York seamstress who came of age during World War II. Brown's straightforward, charming depiction illuminates the vivacious young woman the wistful elderly narrator remembers, and her conversational pacing creates vibrant pictures for the listener. The action is set in 1940, after Vivian dropped out of Vassar and moved to Manhattan to help her aunt run a decrepit theater company. She also created stunning costumes for the company, including a middle-aged British actress memorably rendered by Brown. On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong, read by Ocean Vuong (Penguin Audio) The author narrates the story of a young Vietnamese immigrant to the U.S. who is completing a letter to his mother, who cannot read. As both author and narrator, Vuong is in the perfect position to narrate the audiobook just as it was intended. His delivery gives even more power to the captivating prose, keeping the listener hooked as the main character, Little Dog, discovers what it means to be young, gay and Vietnamese in a country that is not able fully to understand him. The listener is carried along with Vuong's voice, almost as if listening to a carefully crafted melody.

On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong, read by Ocean Vuong (Penguin Audio) The author narrates the story of a young Vietnamese immigrant to the U.S. who is completing a letter to his mother, who cannot read. As both author and narrator, Vuong is in the perfect position to narrate the audiobook just as it was intended. His delivery gives even more power to the captivating prose, keeping the listener hooked as the main character, Little Dog, discovers what it means to be young, gay and Vietnamese in a country that is not able fully to understand him. The listener is carried along with Vuong's voice, almost as if listening to a carefully crafted melody. Stay Sexy & Don't Get Murdered by Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark, read by Karen Kilgariff, Georgia Hardstark, Paul Giamatti, et al. (Macmillan Audio) Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark team up to narrate their dual memoir. They are unapologetically vulnerable as they share their stories about depression, addiction, and learning to value their personal safety over being "nice." The story is delightfully peppered with sections in which actor Paul Giamatti offers wise quips, and some parts of the audiobook are performed in front of a live audience, frequently making the listener laugh out loud.

Stay Sexy & Don't Get Murdered by Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark, read by Karen Kilgariff, Georgia Hardstark, Paul Giamatti, et al. (Macmillan Audio) Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark team up to narrate their dual memoir. They are unapologetically vulnerable as they share their stories about depression, addiction, and learning to value their personal safety over being "nice." The story is delightfully peppered with sections in which actor Paul Giamatti offers wise quips, and some parts of the audiobook are performed in front of a live audience, frequently making the listener laugh out loud.