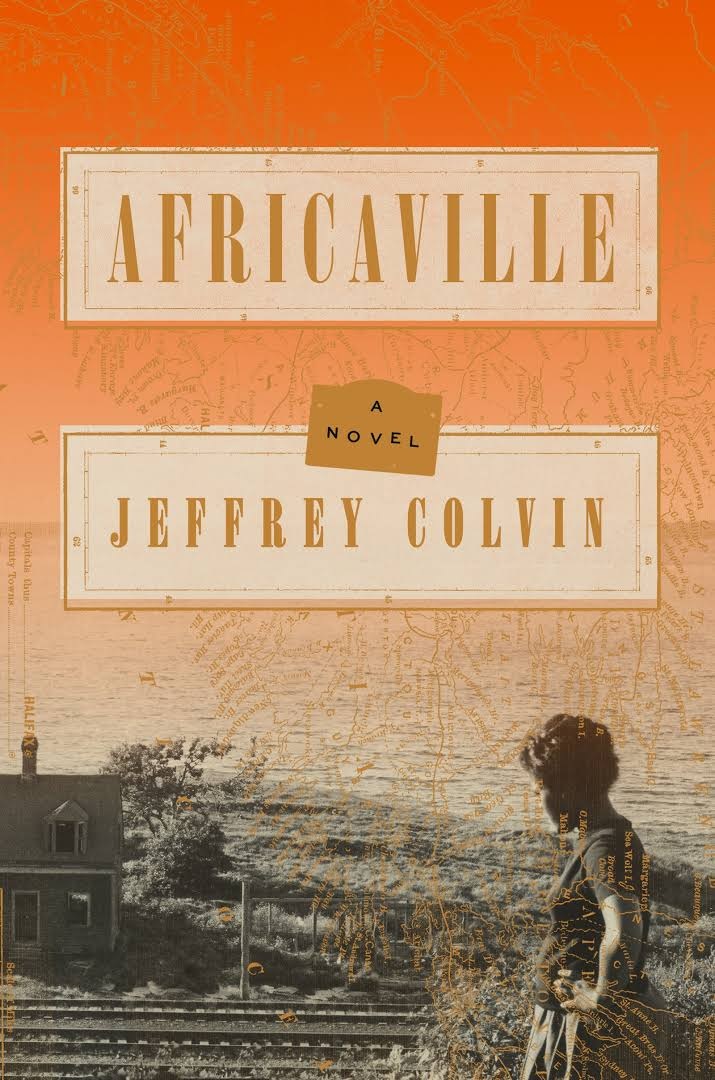

The town of Africville exists, designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1996. The small coastal community on the edge of Halifax, Nova Scotia, was home to black residents since the early 1800s, the majority with southern U.S. and Caribbean origins. Narrative magazine assistant editor Jeffrey Colvin mines the settlement's little-known history to create his epic debut novel, Africaville, the result of 20 years of research and writing. Colvin follows four generations of a widely scattered family over most of the 20th century in a peripatetic journey that crosses multiple borders: between identities defined and denied by skin color and complicated relationships, between freedom and imprisonment, between truth and omission.

The town of Africville exists, designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1996. The small coastal community on the edge of Halifax, Nova Scotia, was home to black residents since the early 1800s, the majority with southern U.S. and Caribbean origins. Narrative magazine assistant editor Jeffrey Colvin mines the settlement's little-known history to create his epic debut novel, Africaville, the result of 20 years of research and writing. Colvin follows four generations of a widely scattered family over most of the 20th century in a peripatetic journey that crosses multiple borders: between identities defined and denied by skin color and complicated relationships, between freedom and imprisonment, between truth and omission.

Kath Ella and Omar--acquainted since childhood--share a brief summer romance that ends with pregnancy and death. Years before, in 1923 Mississippi, the incarceration of Matthew and Zera Platt--"for mischief at the governor's houseboat"--enabled the young lovers' eventual union; the Platts' six-year-old son, Omar, was sent to be raised by his Canadian grand-uncle in Halifax. The adult Omar's fatal accident leaves Kath Ella a single mother to an infant named to memorialize his late father--until Kath Ella marries Timothee, a white man, in Montreal. Timothee was happy to adopt Kath Ella's toddler, but wanted to rename the younger Omar as Etienne. Already the child of light-skinned black parents, Etienne legally becomes a white man's son, effectively dismissing his Africaville heritage for decades.

Etienne continues to increase the distance--emotionally and physically--from his Canadian birth by marrying and having a son of his own, moving to Vermont, then Alabama. He begins his new job at Montgomery A&M, with its now "thirty percent colored" student population, where he's hired to "ensure colored registration did not regress to its former low levels." With his white wife and white upbringing, Etienne's "colored" background remains unrecognized, effaced by perceptions and assumptions he never quite challenges.

As civil rights protests intensify in the early 1960s South, news reports about a local preacher (Martin Luther King, Jr., is implied) hardly elicits a reaction from Etienne. Not until distant (black) Halifax relatives confront him about "crowing"--"that means a colored person is passing for white"--does Etienne begin to acknowledge, albeit half-heartedly--his ancestry. His cursory attempt to visit his grandmother Zera Platt, who is still alive and imprisoned just one state over in Mississippi, is summarily rejected. Years pass, until Etienne's son Walter becomes the connector, forging a circuitous path that finally brings the surviving family "home."

In Colvin's carefully constructed family saga, erasure by death, neglect, loss--both intentional and situational--loom from one generation to the next. Despite departure and distance, Africaville ultimately proves to be a tenacious reclamation of story, of place, of belonging. --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Shelf Talker: The centuries-old yet little-known history of a black coastal settlement in Nova Scotia inspires Jeffrey Colvin's affecting multi-generational debut novel, Africaville.

In September, bookstore sales fell 2.3%, to $954 million, according to preliminary estimates from the Census Bureau. For the first nine months of the year, bookstore sales have fallen 5.6%, to $7.4 billion.

In September, bookstore sales fell 2.3%, to $954 million, according to preliminary estimates from the Census Bureau. For the first nine months of the year, bookstore sales have fallen 5.6%, to $7.4 billion.

IPC.0204.S3.INDIEPRESSMONTHCONTEST.gif)

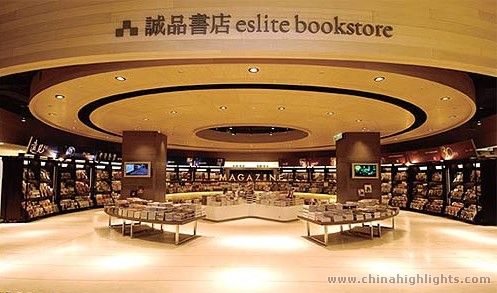

Eslite's bookstore in the Daan neighborhood of Taipei, Taiwan, which claims the title of "the first 24-hour bookstore in the world," is

Eslite's bookstore in the Daan neighborhood of Taipei, Taiwan, which claims the title of "the first 24-hour bookstore in the world," is

IPC.0211.T4.INDIEPRESSMONTH.gif)

Atria and Skillset magazine teamed up to promote Jack Carr's thriller series Terminal List with this car entered in the 2019 Buckeye Demolition Derby this past Saturday. The Carr car gave a valiant effort, but ultimately had to quit after several jarring hits broke the throttle.

Atria and Skillset magazine teamed up to promote Jack Carr's thriller series Terminal List with this car entered in the 2019 Buckeye Demolition Derby this past Saturday. The Carr car gave a valiant effort, but ultimately had to quit after several jarring hits broke the throttle. Upon the Flight of the Queen

Upon the Flight of the Queen The town of Africville exists, designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1996. The small coastal community on the edge of Halifax, Nova Scotia, was home to black residents since the early 1800s, the majority with southern U.S. and Caribbean origins. Narrative magazine assistant editor Jeffrey Colvin mines the settlement's little-known history to create his epic debut novel, Africaville, the result of 20 years of research and writing. Colvin follows four generations of a widely scattered family over most of the 20th century in a peripatetic journey that crosses multiple borders: between identities defined and denied by skin color and complicated relationships, between freedom and imprisonment, between truth and omission.

The town of Africville exists, designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1996. The small coastal community on the edge of Halifax, Nova Scotia, was home to black residents since the early 1800s, the majority with southern U.S. and Caribbean origins. Narrative magazine assistant editor Jeffrey Colvin mines the settlement's little-known history to create his epic debut novel, Africaville, the result of 20 years of research and writing. Colvin follows four generations of a widely scattered family over most of the 20th century in a peripatetic journey that crosses multiple borders: between identities defined and denied by skin color and complicated relationships, between freedom and imprisonment, between truth and omission.