With independent booksellers immersed in their holiday handselling season, I'd like to pause for just a moment and consider an extraordinary reading list I spent some time with last weekend inside the stone walls of Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York.

|

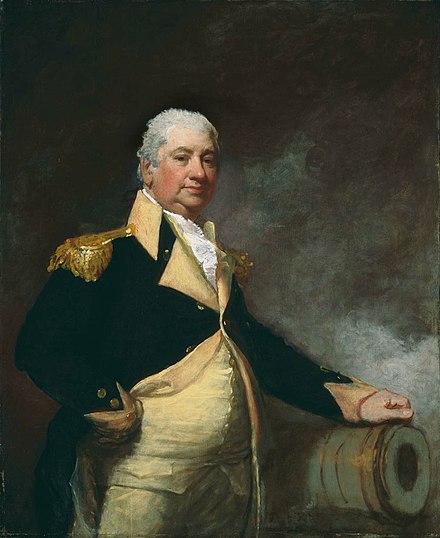

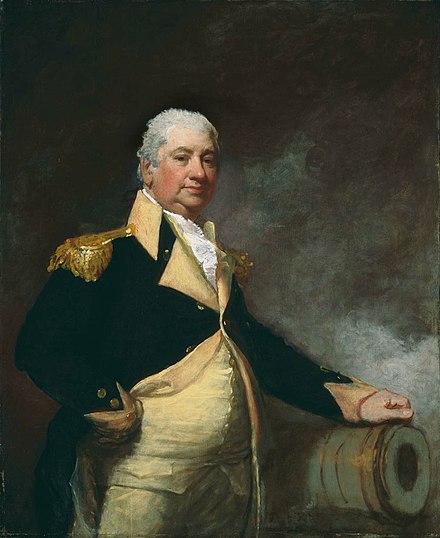

Henry Knox

(portrait by Glibert Stuart) |

Imagine you're a Colonial-era bookseller who receives a letter, dated November 11 1775, from John Adams requesting book recommendations--staff picks, 18th-century style. And yes, it's that John Adams, who specifically asks for advice regarding "books upon the Military art in all its Branches."

If you're an excellent bookseller like Henry Knox, owner of the London Book-Store in Boston, you would normally put on your handseller's tricorn hat and get to work. Due to extenuating circumstances, however, Knox's answer was delayed for several months because he had already left Boston on an epic business trip.

Just before Independent Bookstore Day last April, I wrote about Knox, an iconic bookseller who played an instrumental role in the War of Independence when he conceived and executed the daring relocation, during the winter of 1775-76, of more than 50 captured British cannons overland from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston--an arduous journey of nearly 300 miles--to help end the British siege of the city.

Just before Independent Bookstore Day last April, I wrote about Knox, an iconic bookseller who played an instrumental role in the War of Independence when he conceived and executed the daring relocation, during the winter of 1775-76, of more than 50 captured British cannons overland from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston--an arduous journey of nearly 300 miles--to help end the British siege of the city.

Knox eventually rose to the rank of Major General, and later served in President George Washington's cabinet. But during the spring of 1776, in a spare moment between completing that nearly impossible mission and moving on to what would prove to be a long campaign under General Washington's command, Knox did finally compile a list of books for Adams.

Last Saturday, I took advantage of an opportunity to spend some time with those titles. Fort Ticonderoga was featuring a one-day exhibit, drawn from the fort's rare book collection, that reconstructed the Adams reading list. Unlike Knox, I made a not-so-harsh December journey north to the fort along a paved highway on the western shore of Lake George, to pay my respects to a bookseller and his recommendations.

After a short walk uphill from the snow-covered parking lot, I entered the fort, walked past a huddle of Revolutionary War reenactors gathered around a campfire, and headed for the building where the books were displayed in spartan surroundings.

As anyone who has spent their life under the spell of books knows, ghosts haunt old volumes in the best possible way, even when they are protected by security glass. Inside the fort, in the presence of those centuries-old titles, with the scent of wood smoke thick in the air, time became irrelevant.

Knox's list included French and British authors and covered topics such as artillery, fortifications and engineering that he felt were "necessary for a people struggling for Liberty and Empire."

Knox's list included French and British authors and covered topics such as artillery, fortifications and engineering that he felt were "necessary for a people struggling for Liberty and Empire."

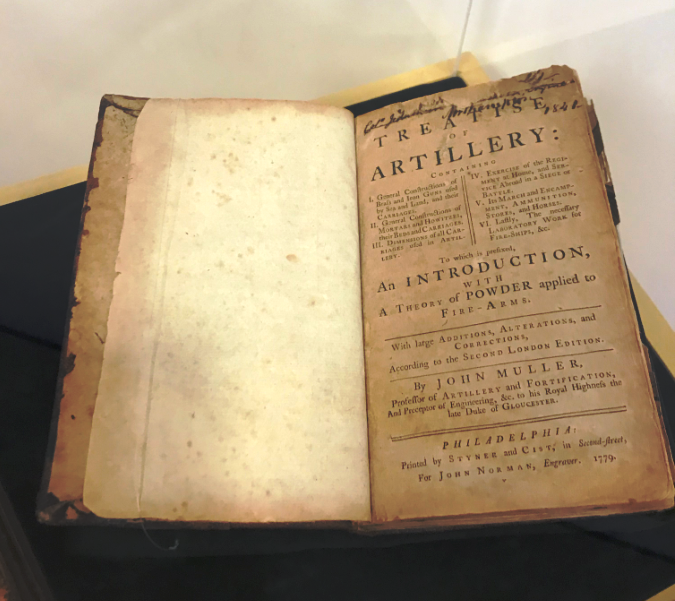

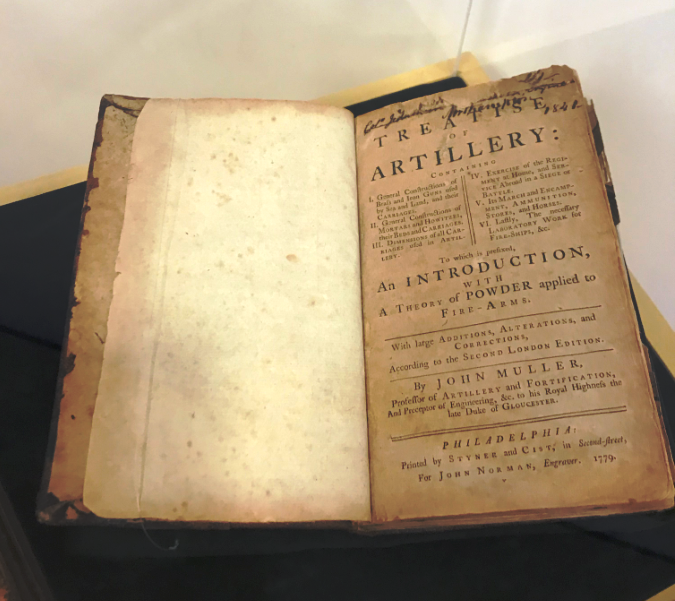

Among these titles were John Muller's A Treatise of Artillery, first printed in 1757 and later published in Philadelphia (1779) in an edition dedicated to George Washington, Henry Knox and the officers of the Continental Army; and Mes Rêveries: Ouvrage Posthume De Maurice Comte De Saxe (1758), of which Knox told Adams: "There are a variety of Books translated into English which would be of great Service but none more so than the great Marechal Saxe 'who stalks a God in war' "

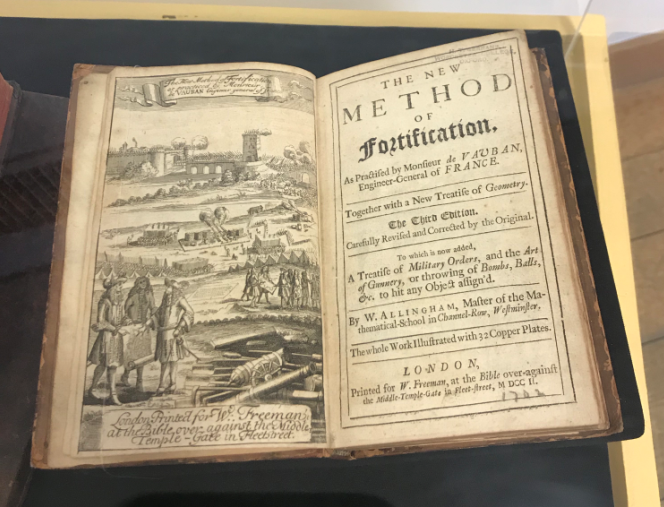

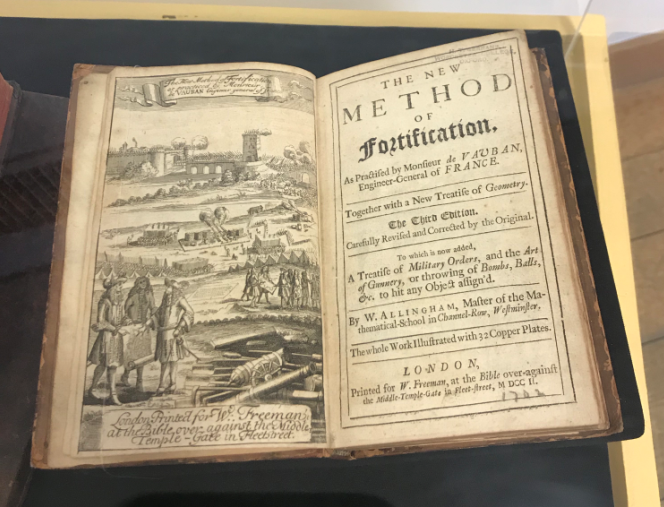

Also on exhibit were The New Method of Fortification as Practiced by Monsieur de Vauban, Engineer General of France (1702); Nouvelle Manière de Fortifier les Places (1699); A Treatise Containing the Elementary Part of Fortification, Regular & Irregular (1756); Les Fortifications (1745); L'Ingénieur de Campagne, ou Traité de la Fortification Passagère (1749); and La Science des Ingenieurs (1729).

Also on exhibit were The New Method of Fortification as Practiced by Monsieur de Vauban, Engineer General of France (1702); Nouvelle Manière de Fortifier les Places (1699); A Treatise Containing the Elementary Part of Fortification, Regular & Irregular (1756); Les Fortifications (1745); L'Ingénieur de Campagne, ou Traité de la Fortification Passagère (1749); and La Science des Ingenieurs (1729).

While none of these titles is likely show up on holiday gift lists this year, my little pilgrimage to Fort Ticonderoga was a compelling reminder that books and booksellers make a difference in the world.

While none of these titles is likely show up on holiday gift lists this year, my little pilgrimage to Fort Ticonderoga was a compelling reminder that books and booksellers make a difference in the world.

In a 2005 speech, author David McCullough said that when Washington took command of the Continental Army during the summer of 1775, he selected two men as the best he had: Nathanael Greene and a 25-year-old bookseller named Henry Knox, "a big, fat, garrulous, keenly intelligent man who... had only about the equivalent of a fifth-grade education but had never stopped reading. He, too, knew of the military only what he had read in books. But keep in mind that this was occurring in the 18th century, their present. It was the Age of Enlightenment, an era when it was widely understood that if you wanted to know something, a good way to learn was to read books...."

Perhaps Henry Knox is my ghost of Christmas past, present and future this year.

Charlie's Corner

Charlie's Corner

Elysia French and Graham Thompson, owners of new Canadian indie

Elysia French and Graham Thompson, owners of new Canadian indie

Congratulations to the

Congratulations to the

Canto, Vol. 1: If I Only Had a Heart

Canto, Vol. 1: If I Only Had a Heart

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for: Celebrated poet Danez Smith (Don't Call Us Dead) delivers a rapturous cry for all their friends and lovers in the profoundly moving collection Homie.

Celebrated poet Danez Smith (Don't Call Us Dead) delivers a rapturous cry for all their friends and lovers in the profoundly moving collection Homie.

Knox's list included French and British authors and covered topics such as artillery, fortifications and engineering that he felt were "necessary for a people struggling for Liberty and Empire."

Knox's list included French and British authors and covered topics such as artillery, fortifications and engineering that he felt were "necessary for a people struggling for Liberty and Empire." Also on exhibit were The New Method of Fortification as Practiced by Monsieur de Vauban, Engineer General of France (1702); Nouvelle Manière de Fortifier les Places (1699); A Treatise Containing the Elementary Part of Fortification, Regular & Irregular (1756); Les Fortifications (1745); L'Ingénieur de Campagne, ou Traité de la Fortification Passagère (1749); and La Science des Ingenieurs (1729).

Also on exhibit were The New Method of Fortification as Practiced by Monsieur de Vauban, Engineer General of France (1702); Nouvelle Manière de Fortifier les Places (1699); A Treatise Containing the Elementary Part of Fortification, Regular & Irregular (1756); Les Fortifications (1745); L'Ingénieur de Campagne, ou Traité de la Fortification Passagère (1749); and La Science des Ingenieurs (1729).