Judy Blume, beloved writer and now a bookseller at Books & Books at the Studios in Key West, Fla., spoke with Shelf Awareness by phone from her daughter's hometown of Cambridge, Mass., where she and her husband and co-bookseller, George Cooper, have been staying since July. We began with the 50th anniversary of Are You There, God? It's Me, Margaret. (out today from Atheneum/S&S, $10.99, paperback) and her editor Dick Jackson, and also spoke of her fight against censorship, her passion for bookselling and... her superpower.

Judy Blume, beloved writer and now a bookseller at Books & Books at the Studios in Key West, Fla., spoke with Shelf Awareness by phone from her daughter's hometown of Cambridge, Mass., where she and her husband and co-bookseller, George Cooper, have been staying since July. We began with the 50th anniversary of Are You There, God? It's Me, Margaret. (out today from Atheneum/S&S, $10.99, paperback) and her editor Dick Jackson, and also spoke of her fight against censorship, her passion for bookselling and... her superpower.

Congratulations! Does it feel like it's been 50 years since Are You There, God? It's Me, Margaret. came out?

Of course not! Oh my God!

I remember vividly, even now, the feeling of relief I had when I read it. You and Margaret helped so many of us understand our bodies and our spiritual yearnings.

I remember vividly, even now, the feeling of relief I had when I read it. You and Margaret helped so many of us understand our bodies and our spiritual yearnings.

How old were you when you read it?

Twelve.

Today it's read by maybe 9- to 12-year-olds, much less on the 12-up side. I don't think the preteens who read it get that spiritual part.

There's no harm in a nine-year-old reading it. But the spiritual seeking is so much a part of adolescence, isn't it?

I wish they would go back. Moms tell me that they didn't get the spiritual quest [when they read it as kids], but they did when they read it again as adults. I'm glad they read it again.

I interviewed Dick Jackson a while back about Margaret, and he said, "Judy didn't set out to rattle cages, she set out to be truthful." Would you agree?

The truth is, I had no idea what I was doing, really. With Iggy's House [also published in 1970] I was like, okay, I figured out how to do this thing. The way you figure it out is you read. I published Iggy's House with Dick. Fifty years ago [when I was writing Margaret], I do remember thinking, "This time I'm going to write what I remember to be true of my life at 12." I had a fabulous memory then. I still have a really good memory about what happened then, just don't ask me where my keys are. I've never lost my memory of being a kid. That's my superpower.

Did I set out to do something specific when I set out to write Margaret? Yes, I set out to tell the truth. But not in a way that's "I am telling the truth." I always have been a spontaneous writer. I write from the gut.

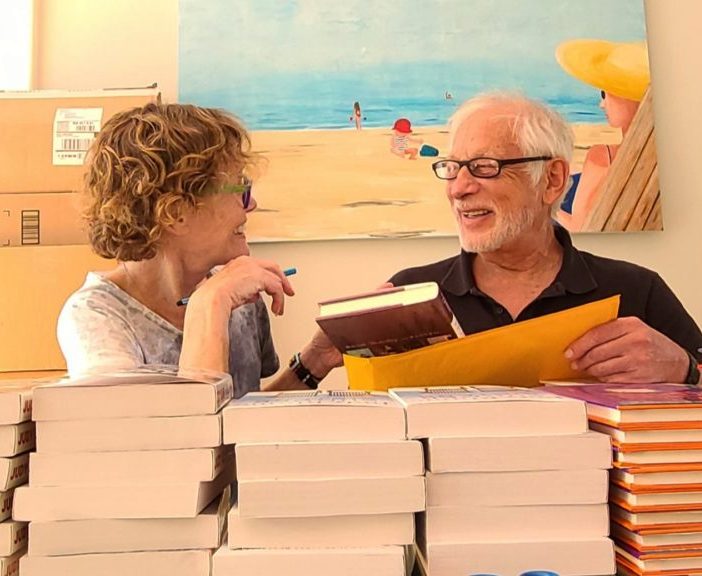

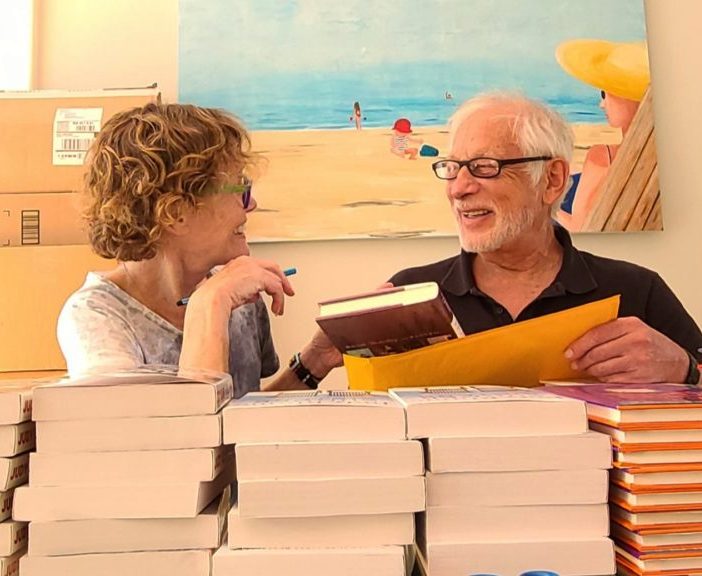

|

| Judy Blume and her husband, George Cooper |

Sally Friedman [Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself, 1977] was my most autobiographical book. That relationship with God really started when I was younger, when I was Sally's age, when I was making bargains with God all the time. For a year in my life I was separated from my beloved father, because we had to go away someplace warm so my brother wouldn't get sick. It was right after the war, '47 and '48. I felt totally responsible for my father's well-being--what a burden for a nine-year-old child! That was how I kept him safe, through my bargains with God. I'll get 100 on my spelling test, if you make sure my father is okay. I had little prayers I invented that I had to say three times a day. If you were a shrink, you might say I became ritualistic. Once we were back together, I let up on that. Of course I never told anybody--this was my secret and my burden.

That relationship with God that I write about in Margaret, that was my relationship with God as confidant. It wasn't so much bargaining with God as talking with God. It's much freer in Margaret than it was in Sally Friedman.

Margaret was the first book of yours that was censored or banned, wasn't it?

Yes, but I'm not sure I knew what was happening then. I did sign three copies and presented them to my kids' elementary school library when it was published. I was very proud. My daughter would have been 10 and my son eight. They had a difficult school principal.

He said the book could not be in the school library, that the discussion of menstruation made it inappropriate for elementary school students. I said, never mind how many kids start their periods at 11 or 12! That was the first it ever occurred to me that someone was going to keep this book away from kids because of a discussion of menstruation.

Do you write many drafts?

Everything was different when I used a typewriter. I sat down and did some kind of first draft, and then I did a second draft. I think it was the third draft I'd send in. Then, with Dick's wonderful help, I would go home and do a fourth draft that was a total rewrite. And then I'd do a fifth draft that would be a polish. With the computer, I've lost track. I could do 20 drafts. My first drafts are for me.

I like the detail, the richness that comes with the later drafts. I'm creating a puzzle and the later drafts put that puzzle together. Dick's genius, apparently, was to figure out the best way to work with each of his writers. Later I'd talk with other people that Dick had worked with--each of us felt he worked only with us. With me, he'd say, "You know so much more than you're telling me in the first drafts I see of your books."

I'd go into Bradbury Press and I'd spend a day talking with him. He did the talking; I did the note taking. Dick always knew the right questions and he didn't make me answer on the spot. Even later, when I worked with other editors, I always heard his questions in my head, and I have to answer them.

How did you become a warrior against censorship, and have you had any challenges in your bookstore?

Margaret was published in 1970. The real push against children's books started in 1980, right after the presidential election. I just watched the series Mrs. America. Cate Blanchett is such a wonderful actor and she made Phyllis Schlafly very likable. Of course, in my mind she's always been the villain. Phyllis Schlafly really went after my books. She once put out a pamphlet called "How to rid your school of Judy Blume books"!

That's when I found the NCAC [National Coalition Against Censorship]--not for my own books but because so many books were being challenged and sometimes banned in school libraries. It was the '80s when the censors were at their worst. There was no such thing as a "safe book." Writers would say, "I'm okay, I write safe books." And I would say, "You never know." Anyway, that's a terrible way to write books.

I don't think anyone has ever asked us to remove a book from our shelves. If they did, we'd explain that what's not right for one customer may be exactly right for another. Joyce Meskis, former owner of the Tattered Cover in Denver, is my First Amendment role model. I once testified in court on behalf of Joyce and her store when a group wanted to prevent children from seeing certain books on display. Joyce won her case. Not long ago, some writers of children's and YA books were accused of sexual abuse--not abuse of children but of bad behavior toward women or men. Accused, not convicted. We did not take their books off our shelves. And even if a writer's personal life comes under fire, even if he/she admits to having had affairs or one-night stands, does that mean their books should no longer be read? I leave that decision up to the reader. Right now, we're gearing up for Banned Books Week. We will display books that have been banned or challenged. We'll celebrate them.

Do you miss being at the bookstore?

That's the saddest part for me, aside from all the really terrible things that are happening. I can't get up every day and go to the store. We have a wonderful staff! We're working, but I'm not doing displays and all the things we love to do. We don't feel too old and vulnerable, but our children tell us we are. If Margaret is 50, then it must be true!

Until I had to start talking about writing again, because of Margaret, I only wanted to talk about my bookstore and how exciting it is to get up every day. People would say, "You look so happy." Writing is so hard; I'm not saying bookselling is easy, but it's so pleasurable. I'm not saying writing is not pleasurable, but it's so hard.

Did you always want to open a bookstore?

Did you always want to open a bookstore?

I was not one of those people who wished for a bookstore. It just had to happen because [Key West] had to have one. I'm writing a little piece now called "Be Careful What You Wish For." There's a guy in Key West who's putting together little essays from Key West writers. There are many of us. That's why it's weird we were down to one used bookstore. We wanted Mitchell Kaplan to come down and open a Books & Books! He said, "It's only going to happen if you and George figure out how to do it, how to find a place and pay the rent."

We're nonprofit, and my husband was on the board of the Studios of Key West, a wonderful organization. They bought and renovated a big building. There was a storefront that came with that building. I said to George, "This is it!" It's just become a very beloved place, our bookstore, I'm happy to say. But be careful what you wish for, it's a huge amount of work. It's very hard but it's so rewarding.

We're nonprofit, and my husband was on the board of the Studios of Key West, a wonderful organization. They bought and renovated a big building. There was a storefront that came with that building. I said to George, "This is it!" It's just become a very beloved place, our bookstore, I'm happy to say. But be careful what you wish for, it's a huge amount of work. It's very hard but it's so rewarding.

You've said that In the Unlikely Event (published in 2015) would be your last book.

My last novel. I have this little thing--I've had this idea for a long time. I don't know who it's for, maybe it's just for me and my family. I want to do a memoir of my early years, from the point of view of the child I was. All those family members, all those aunts and uncles, all those siblings of my father's. Just growing up, little secrets my mother would say to me: "Don't tell anybody I know the words to that song 'Silent Night' "--we were Jews, after all. The scene is so clear in my mind, she's making the bed and singing the song. I never told anybody. Not even my father.

What advice would you offer to authors just starting out today?

You don't write unless you have to. And then if you have to, you will do it. And you will do it whether there's a pandemic or not. It could be that this is a very good time to write. Don't let anybody discourage you. I used to write through the worst times in my personal life. My writing saved me. --Jennifer M. Brown, senior editor, Shelf Awareness

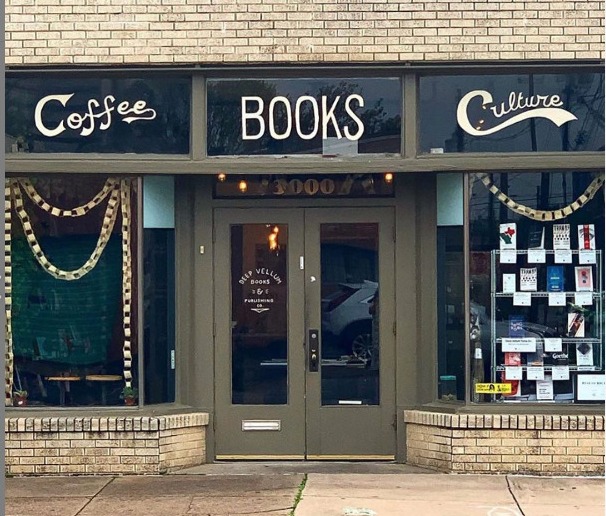

In Dallas, Tex.,

In Dallas, Tex.,  Jennifer Kandarian, manager of

Jennifer Kandarian, manager of

To protect folks who've been overexposed to a certain national political figure,

To protect folks who've been overexposed to a certain national political figure,  Print: A Bookstore

Print: A Bookstore Skunk and Badger

Skunk and Badger

I remember vividly, even now, the feeling of relief I had when I read it. You and Margaret helped so many of us understand our bodies and our spiritual yearnings.

I remember vividly, even now, the feeling of relief I had when I read it. You and Margaret helped so many of us understand our bodies and our spiritual yearnings.

Did you always want to open a bookstore?

Did you always want to open a bookstore? We're nonprofit, and my husband was on the board of the Studios of Key West, a wonderful organization. They bought and renovated a big building. There was a storefront that came with that building. I said to George, "This is it!" It's just become a very beloved place, our bookstore, I'm happy to say. But be careful what you wish for, it's a huge amount of work. It's very hard but it's so rewarding.

We're nonprofit, and my husband was on the board of the Studios of Key West, a wonderful organization. They bought and renovated a big building. There was a storefront that came with that building. I said to George, "This is it!" It's just become a very beloved place, our bookstore, I'm happy to say. But be careful what you wish for, it's a huge amount of work. It's very hard but it's so rewarding. When Iraq War veteran Phil Klay's debut short story collection,

When Iraq War veteran Phil Klay's debut short story collection,