|

| photo: Jane Delury |

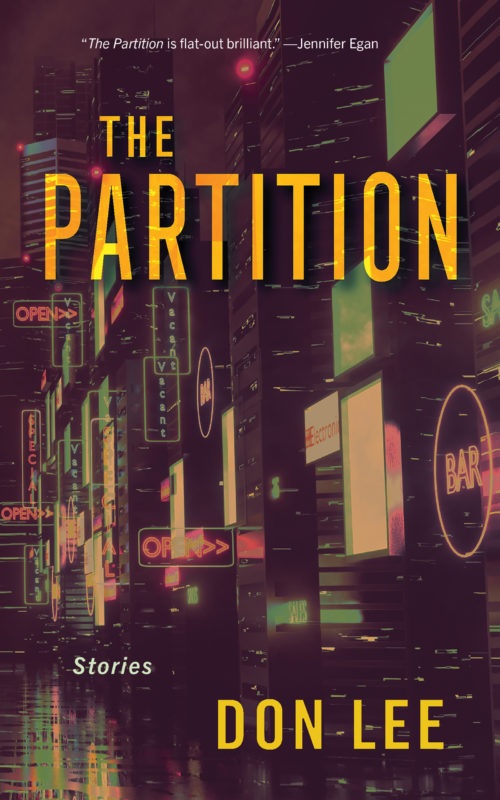

Don Lee's second collection, The Partition (Akashic Books, May 10, 2022), offers nine stories that span decades and cities across the world, shining a light onto contemporary life and the Asian American experience. He is also the author of the story collection Yellow and the novels Country of Origin, Wrack and Ruin, The Collective and Lonesome Lies Before Us. He has received an American Book Award, the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature and the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction. He lives near Baltimore with his wife, the writer Jane Delury, and teaches in the MFA program in creative writing at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

The Partition is an updated look at the so-called Asian American experience, exploring the lives of very American, assimilated Korean American artists, actors, journalists and academics.

On your nightstand now:

Running Away by Jean-Philippe Toussaint. This is one of my favorite books, a short novel by the Belgian writer. It's the second volume of a tetralogy, about a nameless narrator's perpetual breakup with a woman named Marie. I'm teaching a class in the short novel this semester, and I love the way Running Away uses the tropes of a thriller or noir book, posing mysteries, but then leaves them entirely unresolved, which makes it a distinctly European book, I feel.

Favorite book when you were a child:

The Catcher in the Rye, J.D. Salinger, which was the first real book I read, when I was 14. I was stuck in a military transit hotel in Tokyo for the summer, and there was a tiny bookstore in the lobby (I write about the hotel in the story "The Sanno" in The Partition). I picked the novel out at random, attracted to its burgundy spine. It changed my world. I hadn't known that books could be subversive. It made me become a reader.

Your top five authors:

Your top five authors:

Alice Munro is one--I love every single thing she's ever written. As for the other four, I will name specific books rather than authors: John Williams's Stoner, which is the most beautifully heartbreaking book I've ever read; Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go, which took me four tries to get into, but once I did, I was entranced (and then concluded it's essentially the same book as The Remains of the Day); Haruki Murakami's The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, which begins with a prototypical Murakami protagonist making spaghetti, listening to music and receiving a mysterious phone call, but then takes off through literal and metaphysical wormholes that have more depth and punch than anything in his other books; and William Maxwell's So Long, See You Tomorrow, which starts out as a slim, conventional coming-of-age story, but then gets surprisingly experimental, incorporating the point of view of a dog.

Book you've faked reading:

Ulysses, James Joyce. The Dubliners was very accessible, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was challenging but understandable, but then I got flummoxed.

Book you're an evangelist for:

The aforementioned Stoner by John Williams, but with a caveat: it's a really sad book, not for everyone.

Book you hid from your parents:

I never hid a book from my parents, but they did hide one from me. In high school, I was poking through my dad's closet and found a book with photographs of sex positions hidden in a manila envelope.

Favorite line from a book:

"Human speech is like a cracked kettle on which we tap crude rhythms for bears to dance to, while we long to make music that will melt the stars." --Flaubert, Madame Bovary.

Writer who influenced you the most:

Richard Yates. Before going to graduate school in Boston, I was house sitting my parents' condo in Burbank, Calif., and went to a used bookstore in town. I'd never heard of Yates before, but I came across Eleven Kinds of Loneliness and bought it. How could I resist that title? I then read everything of his I could find. I saw in his bio that he lived in Boston, and mused how great it'd be if I could meet him someday. My second night in Boston, I saw him in a bar/restaurant called Crossroads, and I introduced myself to him. He became a mentor of sorts. He was actually dismissive of my writing, but nonetheless he served as a model for me, destroying all the illusions I had that a life as a writer was glamorous, instead schooling me about the dedication and perseverance needed to be a midlist writer who had been forgotten and forsaken by readers, reviewers and the publishing industry (his books largely had gone out of print when he died), and yet who continued to write, day after torturous day. I wrote a piece about this in Electric Literature a while back.

"Well, in my career, they've played an enormous role. Indie booksellers are hugely responsible for the fact that I have this vast readership. But ever since I was a kid, bookstores have felt vaguely magical, like a miniature version of Disneyland, where there are all these immersive worlds just lined up and you can move between them without even trying. That's such an amazing feeling.... Going into an indie bookstore feels a little bit like you’re standing at the intersection of a million other universes, and you can move freely between them. That's the feeling I wanted to capture in the settings in Book Lovers: the coziness, sure, but also the excitement."

"Well, in my career, they've played an enormous role. Indie booksellers are hugely responsible for the fact that I have this vast readership. But ever since I was a kid, bookstores have felt vaguely magical, like a miniature version of Disneyland, where there are all these immersive worlds just lined up and you can move between them without even trying. That's such an amazing feeling.... Going into an indie bookstore feels a little bit like you’re standing at the intersection of a million other universes, and you can move freely between them. That's the feeling I wanted to capture in the settings in Book Lovers: the coziness, sure, but also the excitement."

In the first quarter ended March 31, Amazon net sales rose 7% to $116.4 billion and there was a net loss of $3.8 billion compared to net income of $8.1 billion in the same period in 2021.

In the first quarter ended March 31, Amazon net sales rose 7% to $116.4 billion and there was a net loss of $3.8 billion compared to net income of $8.1 billion in the same period in 2021. Tomorrow is

Tomorrow is  As part of its "Neustart Kultur" (New Start Culture) stimulus package, the German government is giving

As part of its "Neustart Kultur" (New Start Culture) stimulus package, the German government is giving  Cool Idea of the Day from

Cool Idea of the Day from  The inaugural

The inaugural  In honor of National Poetry Month and Mother's Day,

In honor of National Poetry Month and Mother's Day,

Adult Survivors of Toxic Family Members: Tools to Maintain Boundaries, Deal with Criticism, and Heal from Shame After Ties Have Been Cut

Adult Survivors of Toxic Family Members: Tools to Maintain Boundaries, Deal with Criticism, and Heal from Shame After Ties Have Been Cut

Your top five authors:

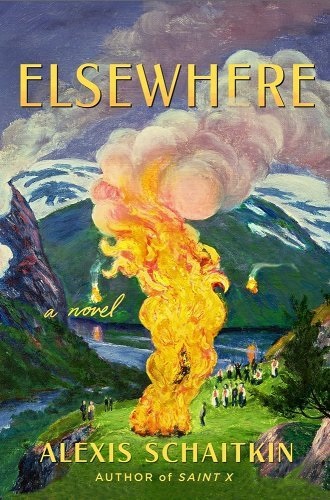

Your top five authors: Alexis Schaitkin (

Alexis Schaitkin (

The inspiration comes from my ongoing impatience with the future. If we can't have flying cars, why not an edge-of-space café & writers retreat? Also, I just read Emily St. John Mandel's amazing novel Sea of Tranquility (Knopf) and one question keeps nagging at me: Are we living in a simulation? If so, why not make the best--or at least the best simulation--of all possible worlds:

The inspiration comes from my ongoing impatience with the future. If we can't have flying cars, why not an edge-of-space café & writers retreat? Also, I just read Emily St. John Mandel's amazing novel Sea of Tranquility (Knopf) and one question keeps nagging at me: Are we living in a simulation? If so, why not make the best--or at least the best simulation--of all possible worlds: Tourism company

Tourism company  Then I read about Tokyo's

Then I read about Tokyo's  My third inspiration came from Meta, Facebook and Instagram's parent company and the primary driver behind the advent of the "metaverse."

My third inspiration came from Meta, Facebook and Instagram's parent company and the primary driver behind the advent of the "metaverse."