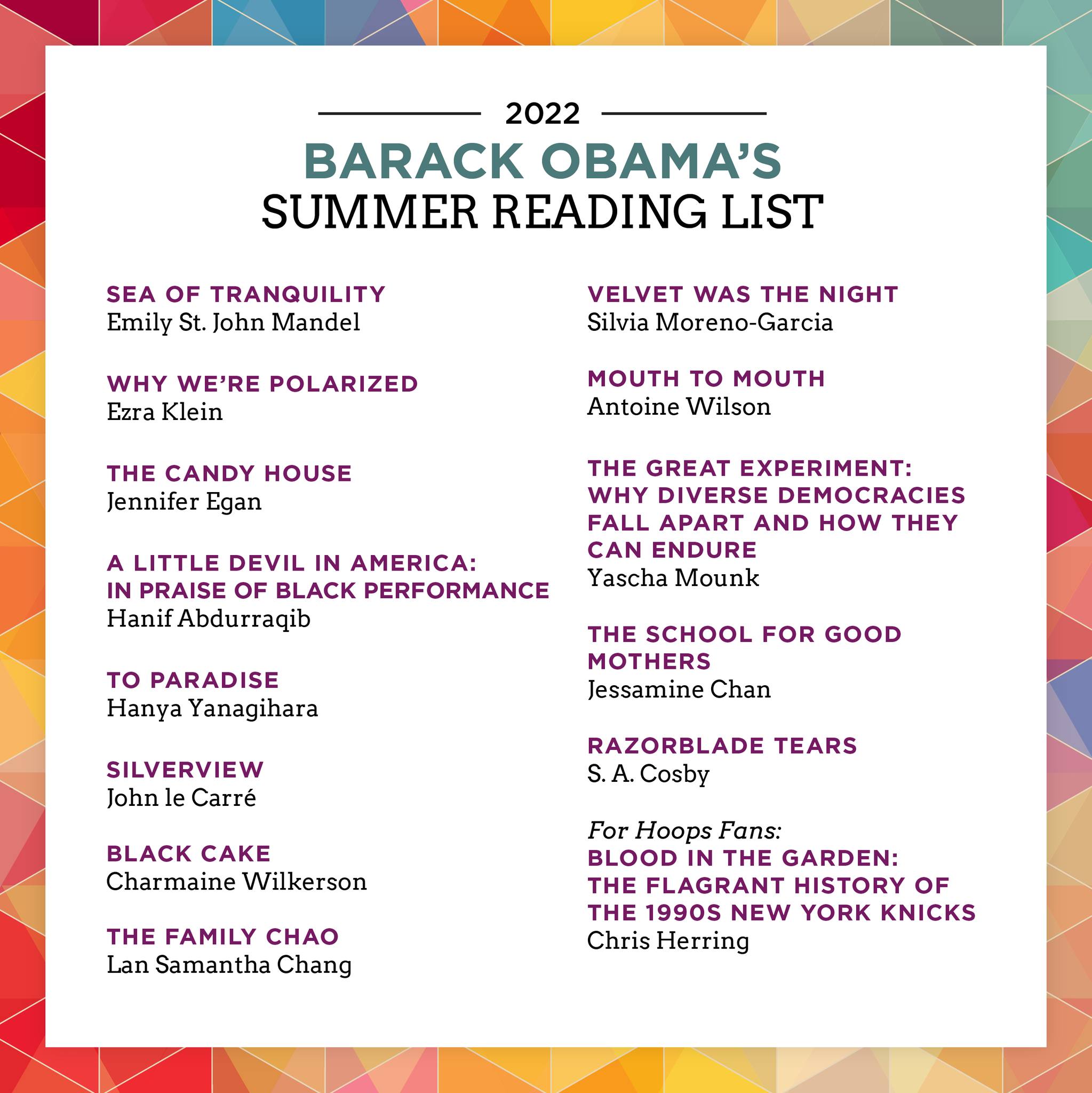

W.P. Wiles was born in India in 1978 and now lives in east London with his wife and two children. He is the author of the Betty Trask Award-winning The Care of Wooden Floors; The Way Inn; and Plume. He also writes about architecture, and is a regular columnist for RIBA Journal. The Last Blade Priest (Angry Robot, July 12, 2022) is his first fantasy novel, an epic grimdark fantasy with rich world-building and a wry take on genre conventions.

W.P. Wiles was born in India in 1978 and now lives in east London with his wife and two children. He is the author of the Betty Trask Award-winning The Care of Wooden Floors; The Way Inn; and Plume. He also writes about architecture, and is a regular columnist for RIBA Journal. The Last Blade Priest (Angry Robot, July 12, 2022) is his first fantasy novel, an epic grimdark fantasy with rich world-building and a wry take on genre conventions.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

A holy mountain, the source of all magic, is guarded by monstrous demigods and a decadent religion. But they are dying.

On your nightstand now:

I tend to read a few things at once. I write about architecture, because I have always enjoyed reading about it, so there's a lot of that alongside fiction. At the moment: Gothic: An Illustrated History by Roger Luckhurst; Queer Spaces: An Atlas of LGBTQIA+ Places and Stories by Adam Nathaniel Furman and Joshua Mardell; The Grace of Kings by Ken Liu; Tell Me I'm Worthless by Alison Rumfitt.

Favorite book when you were a child:

I was very fond of Joan Aiken--both the anarchic comedy of the Mortimer stories and the fantasy of The Wolves of Willoughby Chase. I loved Norman Hunter's Professor Branestawm stories. Terry Pratchett was also a favourite--in particular, The Carpet People.

Your top five authors:

J.G. Ballard; Don DeLillo; Ursula K. Le Guin; Nicola Barker; and the architecture writer Owen Hatherley, who deserves to be known and loved far beyond that narrow world.

Book you've faked reading:

I didn't study English literature at A-level or university, so my knowledge of "the canon" is pretty fragmentary. This means I've nodded my way through a few conversations about, say, Charles Dickens.

Book you're an evangelist for:

"Evangelist" is the right word here. A book I've recommended more than most others is The Pursuit of the Millennium by Norman Cohn, a study of apocalyptic cults and religious uprisings in the Middle Ages. That sounds a little specialist, but it's astounding--on the one hand, akin to epic fantasy in its vastness and weirdness, but also a vital textbook for understanding human beings. Its influence runs right through The Last Blade Priest.

Book you've bought for the cover:

Book you've bought for the cover:

More than I'd like to admit, I have a weakness for the ancient hardback Everyman editions with the gilded decoration on the spine, which look lovely lined up on a shelf. I have another, even more deadly, weakness for thick books. I've recently been packing up my books for a move, so I've found scores of unread hardback novels bought for their covers: David Foster Wallace's The Pale King, Sergio de la Pava's A Naked Singularity. I'll get to them. I don't understand the argument that it's embarrassing to have unread books on your shelves. The whole point of hoarding books is to always have something unexpected to read. Once I've read something, it often goes to charity so that I can save space. Unless it looks nice.

Book you hid from your parents:

My parents had a lot of '60s beatniky stuff--Colin Wilson's The Outsider, Sartre, Nietzsche--so I gnawed unhappily at inappropriate ages through things like Thus Spake Zarathustra and Iron in the Soul without feeling like I had to hide my reading. What I hid was smut--of a relatively innocent kind. Tom Sharpe's bawdy novels, Eric Stanton, that sort of thing. This was before the Internet, you see.

Book that changed your life / Favorite line from a book:

If you'll allow it, I'd like to lump these questions together, because it's the same answer. From We Wish to Inform You that Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families, Philip Gourevitch's vital and upsetting book about the Rwandan genocide:

"to a very large extent power consists in the ability to make others inhabit your story of their reality."

Not a beautiful line but an important one, and one that went off like a grenade inside me when I read it 20 years ago. It's an important truth about the nature of power and the nature of narrative and storytelling. Having read this, I felt like I understood the world around me like never before. It was like being given a key to events and phenomena, even ones that seem baffling or illogical. And I think all writers should have it etched in them, because we are fed a lot of very syrupy self-help stuff about how powerful stories are and how they change lives. And that's absolutely true, but we have to understand that it might not always be good.

Five books you'll never part with:

This will sound bizarre, but I have read The Great Crash, 1929 by James K. Galbraith at least half a dozen times. It's economic history, but it's paced like a thriller and written in a wonderful tone of dry humour. And as a tale of folly and disaster, hubris and nemesis, it's hard to beat. My copy is disintegrating. Ballard's short stories are wells I return to over and over. I wonder if we could cheat and cram them into a single 2,000-page volume. M.R. James's ghost stories are also a continual joy. Keeping things gothic, Thus Were Their Faces by Silvina Ocampo is a treasure house of dark gems. Eleanor Catton's The Luminaries is a novel I could spend a lifetime rereading, I think.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

I have read and reread Iain (and Iain M.) Banks's novels many times, and the pleasure doesn't dim. But I wish I could enjoy their delicious twists for the first time again.

What appeals to you about thick books:

They look handsome on a shelf, but honestly I think there is something special about longer books. It's nice to have a book as a companion for a long time, especially if they're the sprawling, multifaceted kind. I think it's possible that this affection comes from cutting my teeth as a reader on chunky fantasy volumes, but it applies to literary fiction as well. The first really long adult novel I read as a teen was Tom Wolfe's Bonfire of the Vanities, and I remember ploughing through that thinking, hey, this isn't any harder than Terry Brooks. Certainly a lot more fun than Sartre. Anyway, at the moment literary Twitter is agreed that short books are best--the shorter, the better--and I would like to respectfully disagree. Longness is no guarantee of quality, but neither is shortness.

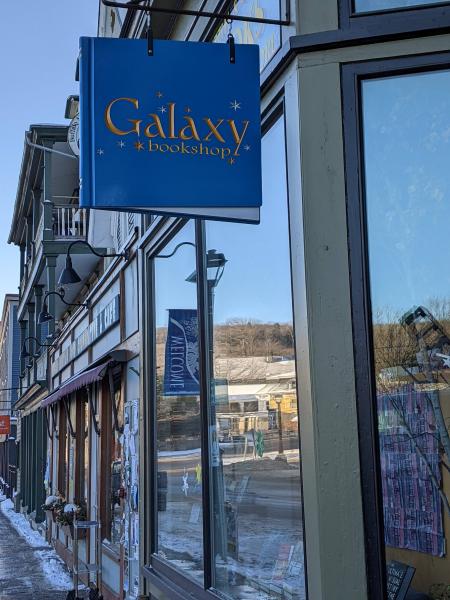

Danielle and Mike Skov are the new owners of

Danielle and Mike Skov are the new owners of

Amazon's main U.K. division

Amazon's main U.K. division

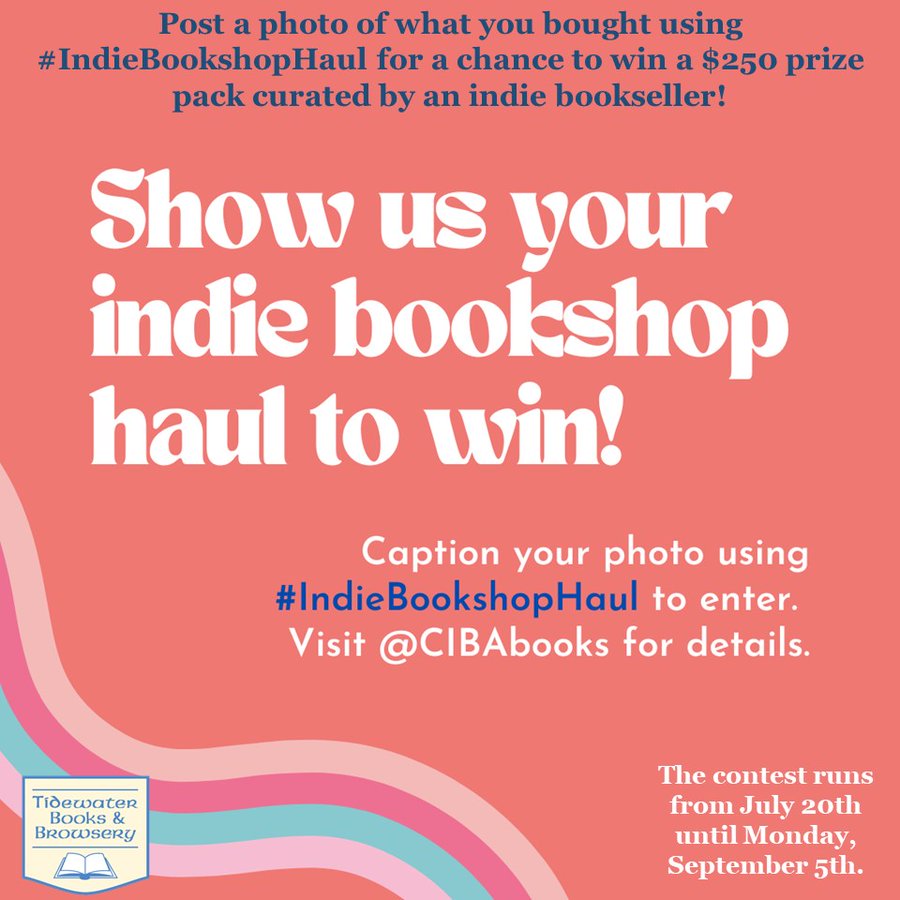

The Canadian Independent Booksellers Association is running a

The Canadian Independent Booksellers Association is running a  Author Nikki Erlick was on Today with Hoda & Jenna to celebrate her debut novel, The Measure (Morrow), being selected as the July Read with Jenna title. Pictured in the studio (l.-r.) are Erlick's editor Liz Stein, Jenna Bush Hager, Nikki Erlick and Hoda Kotb.

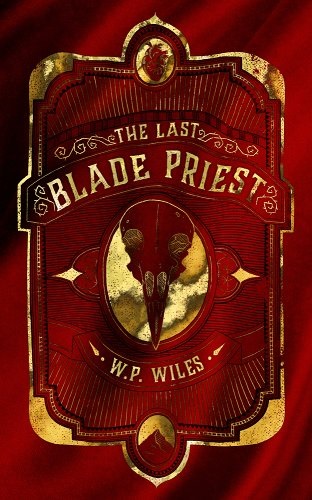

Author Nikki Erlick was on Today with Hoda & Jenna to celebrate her debut novel, The Measure (Morrow), being selected as the July Read with Jenna title. Pictured in the studio (l.-r.) are Erlick's editor Liz Stein, Jenna Bush Hager, Nikki Erlick and Hoda Kotb. Barack Obama has released his summer reading list. On Facebook, he wrote, "

Barack Obama has released his summer reading list. On Facebook, he wrote, "

"When your family is out enjoying the gorgeous weather without you...."

"When your family is out enjoying the gorgeous weather without you...."

Book you've bought for the cover:

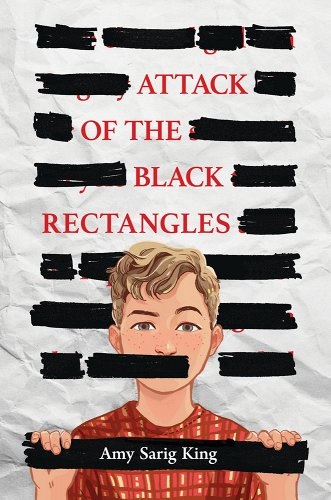

Book you've bought for the cover: A sixth-grader confronts school censorship and tackles his own insecurities in the process in this timely and impassioned middle-grade novel about difficult truths, agency of youth and the importance of having grace in complicated circumstances.

A sixth-grader confronts school censorship and tackles his own insecurities in the process in this timely and impassioned middle-grade novel about difficult truths, agency of youth and the importance of having grace in complicated circumstances.