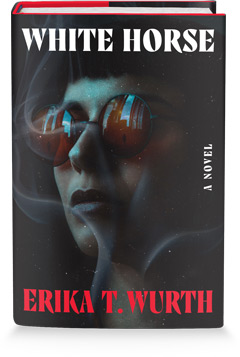

White Horse

by Erika T. Wurth

Erika T. Wurth's White Horse is a raw and evocative piece of literary horror about a Native woman's descent into her own and her mother's past. With its stark settings, bone-chilling revelations and blood-soaked images, this is a modern-day ghost story that takes its hauntings and its monsters seriously.

Kari James has organized her life in recent years around three things: hanging out with her cousin Debby, taking care of her disabled father and drinking at her favorite dive bar, the White Horse. The bar might be rundown and filled with feral cats, but it's become the place that feels most like home for Kari since the tragic death of her best friend Jaime. Since then, Kari has cleaned up her act and lived the straight and narrow, with the exception of her predilections for whiskey, cigarettes and heavy metal.

But when Kari touches a newly discovered, intricate bracelet once owned by her long-absent mother, she finds herself suddenly haunted by grotesque and disturbing images of a young woman. A young woman who is almost certainly her mother, although not the mother Kari thought she'd be. Kari, who grew up hating her mother for leaving her at birth and spurring the car accident that disabled her father, must now face an alternate version of her past: one in which her mother is not at all the villain of the story.

Chillingly atmospheric, White Horse conjures a world that straddles this one and the next, existing in a smoke-choked liminal space in which the grittiness of reality and the uncanny wonder of the seemingly mystical exist on the same plane. Key to such a world is Wurth's masterful ability to invoke settings ripe with horror potential. From the corners of "dusty used bookstores" to the unsettlingly nostalgic roller rinks of a 1980s childhood, with lights that "flickered pink, then green, highlighting the path in front of us," these settings are the stuff of real places, the places where real poignancy exists. And, yet, they are places where one can sense the presence of something just beneath the surface, just out of reach. The most central and perhaps most engrossing of these settings is the White Horse, part ruins of the past and part hope for the future, a place that has "a milky, dreamy quality to the red lights swinging over the pool tables, like the wind from the open doors was bringing them something new, something I'd pushed away for as long as I could remember."

While White Horse's settings alone tend to give the novel a great deal of atmospheric and thematic appeal, it's Wurth's invigorating blend of genres--from literary horror to classic ghost stories to neo-noir pulp mysteries--that truly creates its distinctive mood. Kari is at once a troubled noir detective and a haunted young woman, but Wurth's dedication to character detail ensures that Kari is also always more complex than any trope. Fiercely loyal, tough-edged but soft-hearted, Kari grounds the novel's often surreal borders, particularly through her complicated but endearing relationship with Debby. If ever one feels it might be easy to drown in the brutality of the events Kari's investigation plumbs, Kari herself is always there to remind readers of the way back.

And White Horse does, indeed, have its share of brutality and horror. Kari's dreams, in particular, will scratch the itch of any horror fan, as will the rusted-out roller coasters and hazy basement heavy-metal bars of Wurth's settings. The monstrous Lofa of Native folklore that lingers in Kari's peripheral vision is particularly disturbing, not just in appearance but in all he comes to represent. Wurth's descriptions never shy away from the visceral nature of this horror, allowing her to evoke a connection between the hair-raising elements of a spiritual beast and its real incarnations. In this way, when the Lofa "begins to tear into [my mother], its long hair caressing her like a lover as it pulls wet, meaty chunks up and out of her neck, her shoulder, her dark hair coated in blood and viscera," the disturbing moments of the novel's horror become inextricably linked to the bodily reality of traumas that its characters dare not remember.

But perhaps the most affecting elements of Wurth's brand of horror aren't her overt descriptions of blood-encrusted bodies, but rather that sensational detail of everyday embodied horror: the "metallic, coppery taste at the back [of the mouth]--almost like blood" and "the smell of scotch, rich and yellow, [that] filled the air and [can raise] the hair on my arms." This insistence upon the link between real and imagined horrors best defines, too, the novel's astoundingly cinematic climax. In this scene, as in the rest of Wurth's novel, violence and trauma are not just the things of nightmares, but horrifying realities one has learned to accept and live alongside every day. --Alice Martin