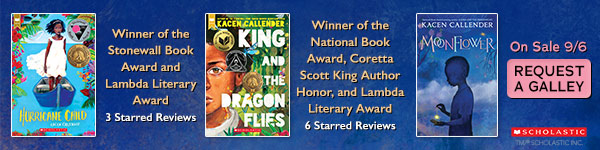

Moonflower

by Kacen Callender

In this extraordinary, resonant middle-grade novel by National Book Award-winner Kacen Callender, 12-year-old Black nonbinary Moon desperately wishes to leave the physical world for the spirit realm. In a narrative that is at once heartbreaking and hopeful, Callender (King and the Dragonflies) masterfully captures the protagonist's complicated journey through captivatingly rich imagery and natural and celestial metaphors.

"The first thing you should know is that I am not from your world," Moon explains. Each night, Moon visits the spirit world, the place "your world is based on," where the sky "is made of swirling colors that look like the solar winds... green and blue and yellow shimmers." Every night, they attempt to gain permanent access so they can leave behind their mortal life. Without fail, at daybreak, Moon awakens, disappointed, in the world of the living. To cope with their emotional and mental anguish, Moon stops speaking. They think, "There's no point in speaking when I can't describe this feeling. It's like a black hole in the middle of my chest. It consumes everything." They find an outlet for their thoughts in a journal where they write about a child named Blue whose life closely mirrors their own. When safely ensconced in the spirit realm, though, Moon is comforted and relieved by the promise of death and thus able to speak freely.

Moon, when tethered to the physical realm, feels misunderstood and hurt by adults' misguided reactions to their lack of interest in speaking. These reactions cover a wide swath: befuddled (Moon's therapist), frustrated and fearful (Moon's mother), completely unaware (Moon's absent father). Without trustworthy mentors in the world of the living, Moon finds solace in their relationship with a shape-shifting spirit in the world of the dead. The first time Moon saw him, he was in the form of a wolf and, since his "real name is something I can't pronounce with my human tongue, in a frequency I can't even hear... the nickname stuck." Wolf, who "must be hundreds of thousands of years old," is the only being in the spirit world who can see Moon--until the Keeper takes notice of the living human child.

Moon believes the Keeper is a protector of the realm who "ensures that only people who are allowed to be there go into the stars." That is, only the dead are welcome. But the Keeper enlists Moon's help: Moon will be sent to gather starlight in exchange for their full admission into the spirit realm. Moon agrees--though Wolf implores them not to--and comes to realize the Keeper is dangerous and destructive.

As Moon moves fluidly between worlds, the "veil between realms gets thinner" and they wonder if perhaps both worlds are imaginary. Soon, their skin begins to fade in and out, and at times Moon feels parts of their body are turning invisible. This sense of physically being and not being illuminates Moon's crippling depression and unyielding suicidal ideation; their feeling of unreality exposes their disconnect from peers and the living world. At the same time, Moon's physical form is being threatened. Moon attends school in a small pod with a virtual teacher because of the constant fear of disease; classmates bully Moon because they don't understand that Moon feels "genderless"; the news frequently reports about violence against Black people.

From the very first sentence, "There is a tree growing inside me," Callender creates in Moon a complex character whose inherent connection to the physical world is deeply at odds with how disconnected they feel from it. Moon enjoys studying herbs and flowers used for medicinal purposes (many of which become chapter titles) but regrets that "I haven't found the right plant, yet--the one that would cure my sadness." They distrust the prescription medication that their mom and psychiatrist want them to take, saying "it just makes everything cloudy and fuzzy and easy to forget." Even the book's title, Moonflower, suggests a plant aligned with Moon's spirit that blooms only at night, much like Moon's feelings about their nightly experiences.

Callender also uses language itself as a powerful symbol. Words are presented as power, agency and freedom from oppression, which is beautifully juxtaposed with the way depression can silence one's inner voice by questioning one's choices and self-worth. Moon's matter-of-fact narrative tone, their use of declarative sentences and the text's distinct lack of exclamations allows readers a window into their numb, detached reality.

Moon's road to healing is winding, imperfect and mired with self-doubt. Yet moments of hope peek through in the form of spirit guardians who offer gentle guidance. Wolf is a kind, loving presence who persistently describes life's joys and, contrary to Moon's beliefs, their mother loves them and is trying to help. Moon's mom's healing journey parallels their own, and she acknowledges how intergenerational trauma plays into Moon's mental illness: "We make mistakes... which are carried on from generation to generation inside of us, deep in our skin.... I don't think I've ever let myself realize, until now, how much pain can be passed down."

Callender's exquisite portrayal of Moon subtly, achingly depicts the inner life of a child living with depression and suicidal ideation. Moonflower is a powerful story that speaks poetically to children and tweens seeking belonging and understanding. Through their magical, mystical world of the dead and Moon's deeply painful, all-too-real experience, Callender displays once again that they have well earned their place within the fantasy canon. Callender delivers another tremendously affecting and ultimately uplifting work for young readers. --Kieran Slattery