|

| photo: Anna Longworth |

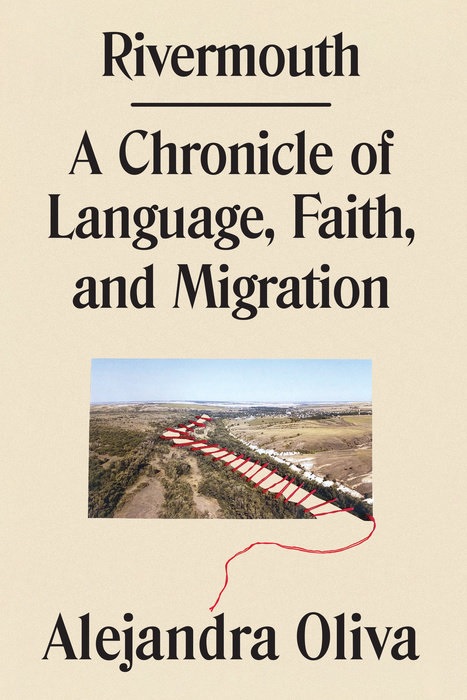

Alejandra Oliva is an essayist, embroiderer, and translator. Her writing has been included in Best American Travel Writing 2020, was nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and was honored with an Aspen Summer Words Emerging Writers Fellowship. She is the author of Rivermouth: A Chronicle of Language, Faith, and Migration (Astra House), for which she received the 2022 Whiting Creative Nonfiction Grant. She was the Yale Whitney Humanities Center Franke Visiting Fellow in Spring 2022. She lives in Chicago with her husband and her dog.

Handsell readers your book in approximately 25 words or less:

A chronicle on the human-ness of immigration through the lens of a translator, weaving together my heritage, meditations on language, and experience translating at the border.

On your nightstand now:

I'm finally reading R.F. Kuang's Babel, which in a lot of ways feels like a perfect companion piece to my book. It's like a fictional examination of the ways that translation, empire, and language can work both in concert and against each other--and the particular complicities of being a translator. It's also just total catnip for my translation-theory-nerd brain. I'm also working my way through Derecka Purnell's Becoming Abolitionists, which is such a lovely invitation into imagining a better, more supportive future.

Favorite book when you were a child:

I grew up as a book-loving, deeply romantic outdoor child in small-town Massachusetts, so Louisa May Alcott's Little Women always had a particular hold on me. Rereading it today, it's so strong on the religious moralizing (something I also grew up with), but I love Greta Gerwig's adaptation.

Your top five authors:

Annie Dillard and Anne Carson are where theory meets beauty for me. Every time I pick up a Valeria Luiselli book, I'm blown away by her inventiveness. Marilynne Robinson's nonfiction manages to make me a little Calvinist every time I read it, and her fiction is full of beauty and complicated goodness. Hanif Abdurraqib writes feelings like absolutely nobody else.

Book you've faked reading:

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. I'll get to it someday, but I did pretend to read significant portions of it for a class in college.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Steven W. Thrasher's The Viral Underclass. I had already been thinking about the ways that all these different struggles for liberation and justice were interrelated, but Thrasher's writing really made clear and vivid to me the way that all these things are part of really just one fight for a better world. Part two of this answer is Gideon the Ninth/the Locked Tomb series by Tamsyn Muir. If you have ever stood next to me at a party three beers in, I have talked to you about lesbian necromancers in space + Eucharistic theology = so many feelings and even more theories.

Book you've bought for the cover:

Sofi Thanhauser's Worn: A People's History of Clothing has one of the best covers I've ever seen: a woman's face, woven together with scraps of paper or fabric. It's so evocative and quiet and fitting with the theme.

Book you hid from your parents:

Unfortunately, the answer to this is: so many Nicholas Sparks books. (So. Many.) Nothing against Nicholas Sparks, but his work constituted an over-large portion of my reading for an over-long period of time--and there are much more fun romance novels out there.

Book that changed your life:

Kate Briggs's This Little Art. This was maybe the first piece of translation theory I read and, as such, maybe one of the first pieces of writing that in some way addressed what it was like to balance between two languages, to love literature, to do translation. It made translation feel like the kinds of relationships I already had with books and reading and both English and Spanish, and it helped me realize that it was worth reading about, thinking deeply about, getting involved in. By that same token, Valeria Luiselli's Tell Me How It Ends took immigration from an abstract issue happening somewhere else and brought it home to me as something I could get involved in, something that needed people with skills like mine.

Favorite line from a book:

Wisława Szymborska's book Map contains the (untitled) poem that my now-husband read to me on one of our very early dates and that we then read at our wedding and inscribed part of in our wedding bands. The whole poem is about the miraculous nature of being alive, but my favorite lines are the ones that close the poem:

"And it so happened that I'm here with you./ And I really see nothing/ usual in that."

Five essays you'll never part with (and the books they appear in):

Annie Dillard's "An Expedition to the Pole" from Teaching a Stone to Talk. It's the closest thing I've read to what God/church/faith feels like to me.

Anne Carson's "Variations on the Right to Remain Silent" from her chapbook-book Float. Translation, Joan of Arc, Hölderlin, Francis Bacon, and the silences that spring up between languages. Perfection.

Thomas Merton's "Letter to an Innocent Bystander" from Raids on the Unspeakable. Like a lot of Merton, it seems almost conversational and friendly at first, and then it turns into an excoriation on the inactive, the passive resisters, the bystanders--and a call to urgency and action. It, alongside the next essay, "The Time of the End Is the Time of No Room," forms a solid argument for becoming an active participant in history.

Helen Macdonald's "The Numinous Ordinary" from Vesper Flights. About finding God, or something like it, in an ordinary cassette tape and being very lonely when you're young.

Lina Mounzer's "War in Translation: Giving Voice to the Women of Syria," which appears in Aster(ix)'s "Kitchen Table Translation" issue. A perfect rendering of what it feels and looks like when your history and your selfhood and your translation are entangled.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Probably Anne Carson's Eros the Bittersweet, although that also has a lot to do with the time of life I was in while reading it. I first encountered that book about three months after meeting my husband and, reading it now, it's full of the absolute corniest annotations possible, as well as some that are the seeds of ideas I ended up exploring in Rivermouth a few years later. Reading that book for the first time felt like all these possibilities opening up in front of me.

The End: a bookstore will host a grand opening celebration next week in Allentown, Pa., the Valley Ledger reported.

The End: a bookstore will host a grand opening celebration next week in Allentown, Pa., the Valley Ledger reported.

IPC.0204.S3.INDIEPRESSMONTHCONTEST.gif)

Spencer Ruchti and Justin Walls are launching the

Spencer Ruchti and Justin Walls are launching the IPC.0211.T4.INDIEPRESSMONTH.gif)

Penguin Random House is launching

Penguin Random House is launching  The Razorbill Books imprint is being merged into Putnam Books for Young Readers. As explained by Jennifer Klonsky, president and publisher of Putnam Books for Young Readers/Razorbill Books/Dial Books for Young Readers, and Casey McIntyre, v-p and publisher, Razorbill Books, the Razorbill imprint was founded as "a cutting edge teen fiction list" but has over the years "evolved into a broad general interest children's list that aligns perfectly with the mission of Putnam, and so it makes sense to merge these two lists and their terrific editorial teams under the Putnam shingle to create a truly powerhouse imprint bringing to market books for all readers."

The Razorbill Books imprint is being merged into Putnam Books for Young Readers. As explained by Jennifer Klonsky, president and publisher of Putnam Books for Young Readers/Razorbill Books/Dial Books for Young Readers, and Casey McIntyre, v-p and publisher, Razorbill Books, the Razorbill imprint was founded as "a cutting edge teen fiction list" but has over the years "evolved into a broad general interest children's list that aligns perfectly with the mission of Putnam, and so it makes sense to merge these two lists and their terrific editorial teams under the Putnam shingle to create a truly powerhouse imprint bringing to market books for all readers." Amber Lotus Publishing, which publishes calendars that showcase wisdom text and inspirational quotes paired with work by artists and photographers, is becoming an imprint of Andrews McMeel Publishing, the largest calendar publisher.

Amber Lotus Publishing, which publishes calendars that showcase wisdom text and inspirational quotes paired with work by artists and photographers, is becoming an imprint of Andrews McMeel Publishing, the largest calendar publisher. Congratulations to

Congratulations to

"A new month is here, and with it, a

"A new month is here, and with it, a  Wednesdays at One

Wednesdays at One

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for: The immigrant experience is exponentially complicated by a far more commonplace predicament: having to care for children. This is one unavoidable takeaway from Wednesday's Child, Yiyun Li's exquisite collection of stories of multipronged grief and dislocation.

The immigrant experience is exponentially complicated by a far more commonplace predicament: having to care for children. This is one unavoidable takeaway from Wednesday's Child, Yiyun Li's exquisite collection of stories of multipronged grief and dislocation.

Look! Up in the sky! It's a bird! It's a plane! It's Super Book Buyer! Although I think of myself as a words guy, sometimes a devilish little numbers guy voice starts whispering in my ear and I'm lured by the temptations of Percentagelandia. Such was the case recently when I encountered statistics culled from BookNet Canada's

Look! Up in the sky! It's a bird! It's a plane! It's Super Book Buyer! Although I think of myself as a words guy, sometimes a devilish little numbers guy voice starts whispering in my ear and I'm lured by the temptations of Percentagelandia. Such was the case recently when I encountered statistics culled from BookNet Canada's  SBBs were more likely than all book buyers to visit a bookstore, either online or in-person, in 2022, with 69% of SBBs visiting a bookstore in person at least once, compared to 64% of all book buyers. More than 80% of SBBs visited a bookstore online one or more times last year, compared to 73% of all book buyers. They also bought more books online than all book buyers, with 63% buying online and 37% in person, compared to 58% of all book buyers who bought online and 42% who bought in person.

SBBs were more likely than all book buyers to visit a bookstore, either online or in-person, in 2022, with 69% of SBBs visiting a bookstore in person at least once, compared to 64% of all book buyers. More than 80% of SBBs visited a bookstore online one or more times last year, compared to 73% of all book buyers. They also bought more books online than all book buyers, with 63% buying online and 37% in person, compared to 58% of all book buyers who bought online and 42% who bought in person.  Not long after devouring the BooknetCanada stats, I found a

Not long after devouring the BooknetCanada stats, I found a