Fire Shut Up in My Bones

by Charles M. Blow

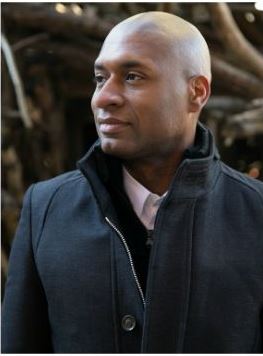

Readers of the New York Times will no doubt be familiar with Charles M. Blow, the newspaper's visual op-ed columnist. In his twice-weekly columns, Blow starts with cold, impersonal data and statistics and uses his insight to turn numbers into impassioned commentary on political and human issues. Now, in a memoir that juxtaposes Blow's usual elegant and eloquent prose with the brutal truths of his early years, he gives issues of race, poverty, sexuality and belonging a human face: his own.

Blow opens with the night he decided to kill his older cousin Chester for abusing him as a young boy. Twenty years old, a college student with a promising career ahead of him, Blow still considered Chester responsible for the confusion and feelings of disconnection from his peers that had plagued him through his entire youth. Finally, Chester's indifference to his crime had to be rectified. Blow then leaves his younger self, armed and weeping with rage, hurtling through the night with murder in his heart. This agonized young man hovers at the edge of the reader's consciousness as Blow backs up to his first memory and walks us along the path that led to that desperate night.

Born in Louisiana in 1970, Blow was the youngest of five brothers, and "by the time I came along, my mother was a dutiful wife growing dead-a** tired of working on a dead-end marriage and a dead-end job. My father was a construction worker by trade, a pool shark by habit, and a serial philanderer by compulsion." Before his parents split up, the family lived in a small rent-to-own house without steps to its tall porch, necessitating entry through the back door. His father could easily have built steps, and the "not-doing spoke volumes," one more example of how he couldn't commit to his family. When the marriage ended, Blow found himself in a new neighborhood and stepping onto a trail of loneliness he'd follow into adulthood. However, his loneliness was not aloneness, and Blow gives us warm character sketches of the family surrounding him at home and supporting him from afar: his grandmother's husband, Jed, who became his much-loved father figure for a time; stubborn Aunt Odessa, who refused modernization in her home; charismatic World War II veteran Grandpa Bill. However, the family's closest companion in Blow's early years was poverty, and he gives a detailed account of growing their own produce by necessity and using every last bit of it, eating clay from a ditch as a treat, scavenging wounded cattle after a stock truck overturned on the highway, and the back-breaking labor the adults around him suffered through to provide for their families. "These were people whose bodies melted every night in a hot bath, then stiffened by sunrise, so much that it took pills to get them out of bed without pain."

Theirs was a community divided by race as well as socioeconomic status, and Blow recalls side-by-side cemeteries, one for blacks and one for whites, separated by a fence lest anyone try to cross an invisible boundary. While racial tension usually played out tacitly, everyone kept to their roles through a rigid social structure, Blow also recounts the first time a white person tossed a racial slur at him, "a perfect little weapon" that suddenly left him questioning the world around him and the injustices his family faced at the hands of whites, and feeling for a time that white people gave him only "jack-o'-lantern smiles--frozen and hollow with a dim light behind the eyes."

While Blow managed to escape falling into the trap of racial hatred himself, his narrative does concern itself in part with the self-hatred that overtook him for many years. After Blow was molested by his cousin, Chester bullied him into silence by repeatedly accusing him of homosexuality in a cultural setting where same-sex relationships were strictly taboo. When Blow reached adolescence and found himself attracted primarily to women but with a curiosity about men as well, it became a secret shame he couldn't eradicate. To hide it, and to conceal the wounds he still carried from Chester's attacks, Blow found himself creating a public face, one that made him a "popular boy" from elementary school through his selection in college to an elite fraternity and its world of privilege and brutality. Even in the darkest moments of his quest to fit in by going along with the crowd, readers will relate to Blow's motivations, to the so-human need to belong, to be wanted, to be singled out as special. They will come to understand that moment when Blow felt Chester must die at his hands, just as they will glory in the freedom and healing he found after struggling through that critical and impassioned moment. That Blow will survive his struggles and accept his own identity is a foregone conclusion. The amazement lies in watching a young man--and Blow makes readers see him in every detail--use his inner compass, his gift for language and the lessons of a past that dogs his heels to release the talented and strong adult he was always capable of becoming. Blow's story reminds us that each child carries the potential to achieve great things, regardless of adversity, but a child without strong advocates--in Blow's case, family members and teachers--is one who may easily become lost and never find the way again.

Amid the ongoing conversations about race relations, sexuality and poverty, Blow casts a new light on the issues simply by telling his own story, using the details of his life to give shape and reality to what many of us understand only in the abstract. If the adage that you can only understand another person by walking a mile in their shoes is true, then Blow not only hands over his shoes, he ties the laces and nudges us in the right direction. As he recounts his memories, explaining with grace and clarity how each instance impacted his psyche, the written word seems to fade from view until only Blow's voice remains, speaking to the human heart in each of us. Although the emotional impact of this memoir cannot be overstated, the tougher moments are tempered by insight and even laughter. Whether readers recognize their own lives in Blow's or simply have their eyes and hearts opened a little wider, no one will come away unaffected. Blow's book-length debut is a drop of hope in an ocean of sorrows. --Jaclyn Fulwood

Charles M. Blow has been a columnist at the New York Times since 2008, is a CNN commentator, and has appeared on MSNBC, CNN, Fox News, Al Jazeera and HBO. Blow lives in Brooklyn with his three children. We recently talked with him about poverty and race in America, life as a single parent, and the experiences that led him to write his upcoming memoir.

Charles M. Blow has been a columnist at the New York Times since 2008, is a CNN commentator, and has appeared on MSNBC, CNN, Fox News, Al Jazeera and HBO. Blow lives in Brooklyn with his three children. We recently talked with him about poverty and race in America, life as a single parent, and the experiences that led him to write his upcoming memoir.