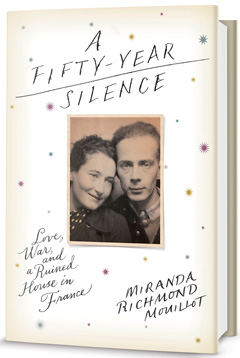

A Fifty-Year Silence: Love, War, and a Ruined House in France

by Miranda Richmond Mouillot

Long after World War II ended in Europe in 1945, the effects of the brutal conflict continued, haunting survivors and rippling from one generation to the next. In A Fifty-Year Silence: Love, War, and a Ruined House in France, Miranda Richmond Mouillot shares the story of two of those survivors: her grandparents, Anna and Armand, both of whom were Jewish.

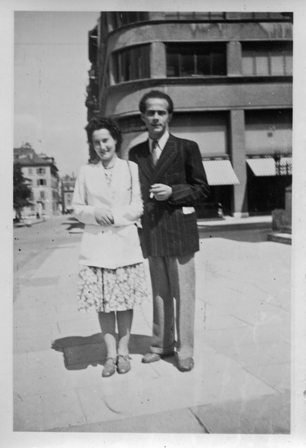

Less than a decade after the couple wed in 1944, Anna walked out on Armand, taking their two children with her. They cut off all contact with one another and never revealed what led to their bitter divide. As a child, Richmond Mouillot had no reason to connect her vivacious, resourceful grandmother, a doctor in New York, with her taciturn grandfather, a translator who lived in Geneva. They hadn't been in the same room or even spoken to each other in decades. In her mind, Anna and Armand were separate entities, occupying different worlds and silent about the life they once shared.

The discovery that her grandparents had once been married shaped the direction of Richmond Mouillot's future. "The more I contemplated it, the more I felt I had no right to go on with my own life until I had learned what had happened in theirs." In 2004, after graduating from college, she moved to France to research and write a book about Anna and Armand and uncover the reason behind their estrangement.

Instead of the year Richmond Mouillot anticipated devoting to the project, it took 10. "There were holes in my plan," she admits. "Two, to be precise: Armand and Anna." They remained resolute in their silence, making it challenging for her to write about a subject no one wanted to discuss. When she began she had barely any factual information, not even the date her grandparents had married. At times she despaired she would ever find anything concrete to illuminate the mystery behind their estrangement and almost abandoned the book altogether.

Instead Richmond Mouillot persevered. Like a detective sifting through evidence, she painstakingly searched for clues. Slowly she pieced together Anna and Armand's story using their refugee files and other sources, including a "jumble" of reminisces her grandmother had written down over the years about her wartime experiences. Richmond Mouillot also coaxed stories from her reticent grandparents, using details gleaned from one to get the other to open up and talk about what had transpired.

Anna and Armand met as students in Strasbourg prior to the outbreak of World War II. During the war years, they struggled to survive, sometimes together and sometimes alone. With a friend's aid, they finally made a harrowing journey out of Nazi-occupied France, crossing snow-covered mountains over the border into Switzerland, where they were placed in different refugee camps.

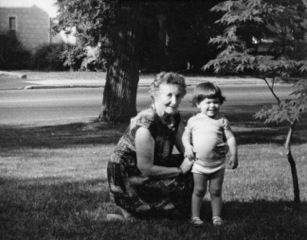

Writing A Fifty-Year Silence helped Richmond Mouillot better understand how her grandparents' experiences impacted her childhood even when she wasn't consciously aware of it. In hindsight, she could see that it related to why she constantly thought about places to hide and why she kept her shoes by the door in case a hurried exit had to be made; why there were always candles and matches at hand in the house and why her mother snapped off the radio or closed the newspaper at the mention of certain subjects.

Later, even as Richmond Mouillot resolved to follow her own path, Armand and Anna "exerted an undeniable influence" over her decisions, including her choice to settle in France, the country where her Romanian grandmother and Swiss-born grandfather had met, fallen in love and feared for their lives; "the country they both regretted and refused to live in, where they'd bought and abandoned an ancient stone ruin."

With her grandmother's encouragement, Richmond Mouillot moved into that ancient stone ruin, a barely habitable house in a medieval village (the place where she met her husband and currently resides). "I believed the very act of living there would be a kind of listening, that it would help me see my way to the truth," she explains. "I felt like an archeologist, or an undersea diver, certain that if I picked through the debris in the house I would find something terrible, or something wonderful, or maybe both, that would provide me with a key, or a hint at least, to the story of their love and separation. Or so I sensed, but the truth was far off to me then."

Eventually Richmond Mouillot found the truth in a place she didn't expect. She delved into an area of Armand's life she had previously overlooked: his postwar years working at the Nuremberg Trials, where he was one of two Jewish interpreters. She had filed away this time in his career as a "proud accomplishment" and then forgotten about it in her quest to learn more about Anna and Armand's relationship because her grandmother hadn't been there. But it was the tragic knowledge Armand acquired at Nuremberg that ultimately broke apart his marriage to Anna.

At one point when Richmond Mouillot was struggling with researching the book, she asked herself, given all the "anonymous drops in the rainstorm of history," was there a point in focusing on Anna and Armand? The answer is a resounding yes. A Fifty-Year Silence is Richmond Mouillot's powerful expression of love for her grandparents and a poignant contribution to the pantheon of Holocaust and World War II literature.

This quietly riveting story is one of love, loss, sadness and survival, with passages so beautifully written you'll want to pause and re-read some of them. Through the lens of her grandparents' lives, Richmond Mouillot explores the legacy of tragedy, the responsibility of keeping history alive and the emotional ravages of war. She flawlessly and compellingly blends Anna and Armand's stories with her own--the need to understand her heritage and make sure her grandparents didn't "disappear" while at the same time forging her own life and identity. Learning, as she says, "to live my life forward, even as the past swirls and eddies around me." --Shannon McKenna Schmidt

Originally from Asheville, N.C.,

Originally from Asheville, N.C.,