The Travels of Daniel Ascher

by Déborah Lévy-Bertherat, trans. by Adriana Hunter

Countless books and films have explored the Holocaust and its effects on those who survived. While estimating the number of lives ultimately affected and the myriad ways in which it shaped them is impossible, the subject inspires ongoing introspection: How much more trauma can original trauma beget, and how can human beings ever move forward once touched by such horrors? In this tightly layered debut novel, Déborah Lévy-Bertherat imagines a man haunted by his World War II childhood, and a family marred by the secrets of the past.

Even as a little girl, Hélène Roche had always found her great-uncle Daniel gauche and embarrassing. The odd one out in a family as sedentary as hobbits, Daniel Roche came to reunions wearing a coat with as many pockets as he had fantastical stories of his world travels. While he held the other children spellbound with tall tales of his daring escapades, Hélène stood unmoved. Her immunity to his charm also extended to The Black Insignia, the bestselling children's adventure series Daniel wrote under the name H.R. Sanders, beloved by her brother and children the world over.

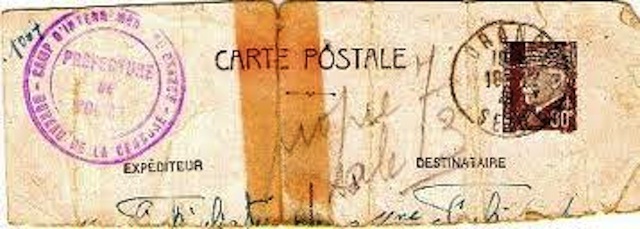

Now a young woman studying at the Institute of Archaeology in Paris, Helene moves into a room Daniel offers her in his nearby apartment building. When hearing her fellow students discussing their excavation experiences, "She thought she'd be a beginner for the rest of her life." However, her work on a children's cemetery dig earns their respect, and her relation to Daniel catches the attention of classmate Guillaume. Like most of their contemporaries, Guillaume grew up on the exploits of Peter, hero of The Black Insignia. He cannot believe Hélène never read the series; imagine having J.K. Rowling as your aunt but never reading Harry Potter. Partly spurred by Guillaume's fascination with Daniel when she introduces them, Hélène becomes curious about her great-uncle and his work. She knows her family adopted Daniel during WWII and successfully hid his identity as a Jewish orphan from the authorities. However, as she investigates his past, every inquiry gives way to more questions about his birth family, the Aschers, and his separation from them, as well as his place in the Roche clan. She begins to scrutinize The Black Insignia,too, trying to work out certain plot discrepancies that have bothered its fans for years, searching beneath the façade of series hero Peter for the true face of Daniel. Her hunt for the truth takes her both across the ocean and into the secrets of her Paris neighborhood, and introduces her to previously unseen sides of her relatives, as well as several strangers, including a concentration camp survivor who tells her, "I wouldn't say I saw death up close in Birkenau. I was inside it, you see.... I was right inside death."

The size ratio between story and page count of this novel somewhat resembles a circus clown car act: the reader opens this petite book to find a sprawling, expansive story. Lévy-Bertherat accomplishes this feat not through sleight-of-hand but through thoughtful construction and layers of meaning. That great pain can lead to great art is hardly a disputed concept, but Lévy-Bertherat encourages the reader to ask what that art represents--a grieving process, a healing catharsis, a hiding place from the pain itself? Readers will be left wondering if fiction can ever be purely false, or if some germ of the author's truth always enters into a work. Moreover, if fiction is a falsehood, does it have the same power to injure as outright lying?

Hélène's initially disaffected view of her great-uncle might reflect youth's customary disdain for elders, or perhaps Hélène senses even as a child that he represents a wrinkle in the fabric of her family. Despite her ambivalence, to the reader Daniel is at once a combination of enigma and the fantasy relative few of us had, one who traveled the world for months at a time and returned with presents and outrageous accounts of his swashbuckling adventures. Although he frequently absents himself from the narrative, when he appears, Daniel charms the reader with his eccentricity and a wistfulness Hélène fails to see at first. The traumas of his childhood, the loss of his true family, have in some ways turned Daniel into something of an adult Peter Pan, a lost boy who lives as a grown up but whose pain retains its immediacy from childhood. At one point, he even seems to fly like Pan, trying on a pair of new shoes and joking, "...this is great, now I'm like the poet Rimbaud, the man with soles of wind." While Hélène works to decide whether he is H.R. Sanders, bestselling author, Daniel Roche, outlandish world traveler, or Daniel Ascher, bereft Jewish orphan, the reader sees him shift among all three roles.

Before publishing a novel, Lévy-Bertherat translated works by Russian writers Mikhail Lermontov and Nikolai Gogol into French. With Daniel, she has created a man who constantly works at translating his past into a palatable story, while Hélène translates the family rumors and scraps of history into a cohesive narrative of Daniel's past. While the Holocaust certainly shaped Daniel's life, anyone who has tried to piece together a family history will relate to this translation loop. With an emphasis on our simultaneous needs to disguise our suffering and tell our stories, Lévy-Bertherat highlights a most human conundrum in a mystery whose resolution will fill readers with sorrow and hope. Ink sketches by Andreas Gurewich help to conjure the Parisian setting and give an air somewhat reminiscent of a children's story, leaving readers to wonder if they have experienced not just Lévy-Bertherat's novel, but a chapter of The Black Insignia as well. --Jaclyn Fulwood

His story is enriched by all sorts of treasures. I walked a lot around my neighborhood, Montparnasse, looking for traces of the past, kind of like Patrick Modiano, whom I admire very much. At Rue d'Odessa, at the bottom of a courtyard, I discovered marvelous public baths.

His story is enriched by all sorts of treasures. I walked a lot around my neighborhood, Montparnasse, looking for traces of the past, kind of like Patrick Modiano, whom I admire very much. At Rue d'Odessa, at the bottom of a courtyard, I discovered marvelous public baths.