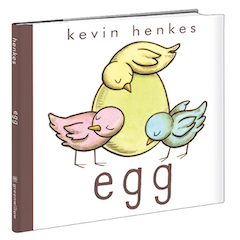

Egg

by Kevin Henkes

Waiting was on Kevin Henkes's mind even before he won a 2016 Caldecott Honor and Geisel Honor for his picture book Waiting--and certainly after that. Thinking about waiting led to his contemplation of the nature of an egg... its secretive, transformative and even suspenseful aspects. In his picture book Egg, preschoolers will wonder when, when, will the last pastel-colored egg hatch? That pale green one sure is taking its sweet time. The reader will just have to wait.

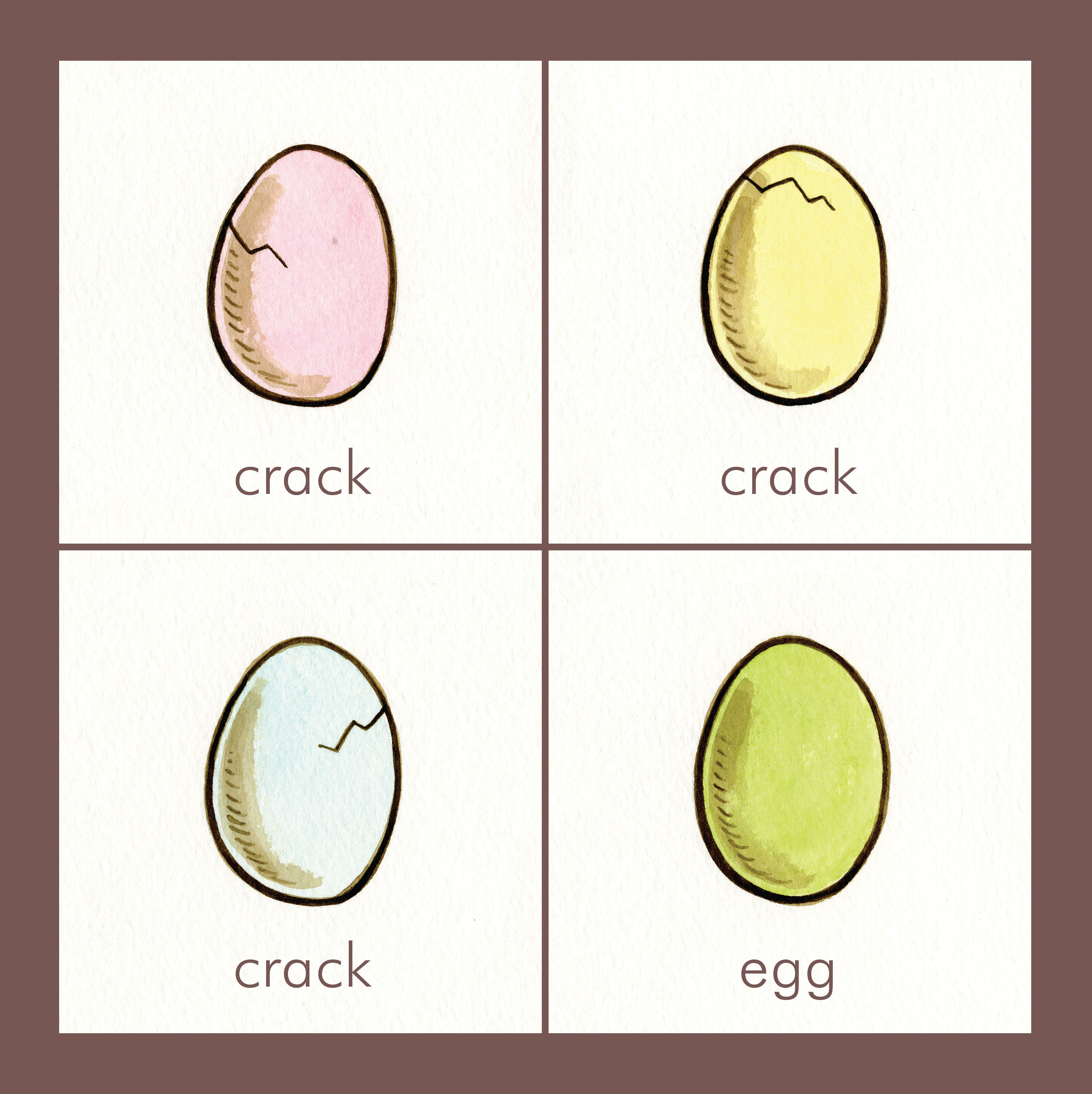

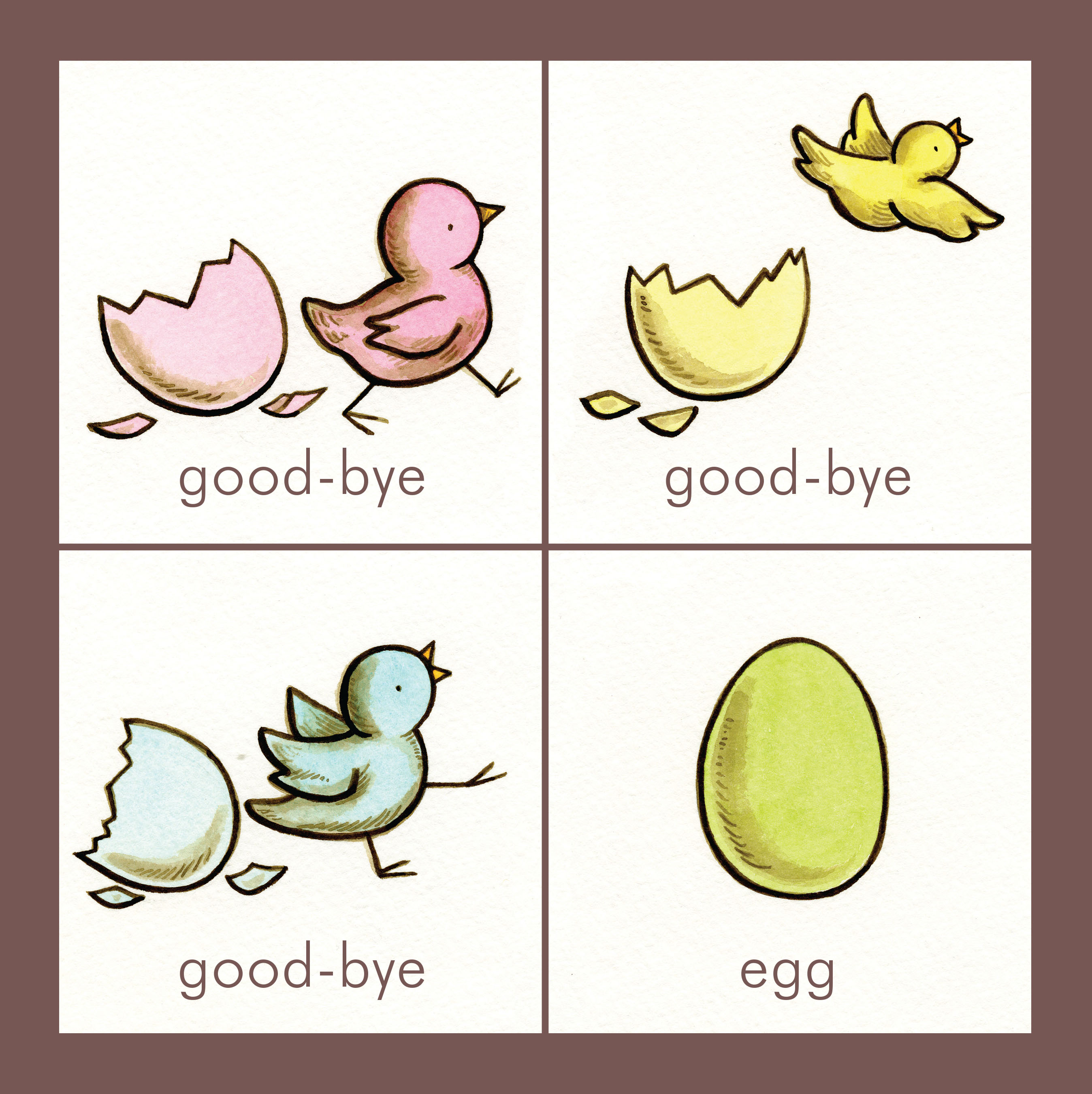

Henkes had fun with Egg, a book he says is "not a traditional story" but is "a graphic novel for preschoolers," due to its simple grid structure that works as basic story panels. The opening page reveals four eggs in four quadrants: pink, yellow, blue and green, all in the same brown ink and watercolor medium Henkes chose for Waiting. Each egg is simply labeled "egg." The facing page is a quadrant, too, and now the pink, yellow and blue eggs are cracking. Each of the three cracked eggs is labeled "crack." But not the green one--it's still labeled "egg."

On the next spread, the pink, yellow and blue eggs in their quadrants hatch into pink, yellow and blue birds ("surprise! surprise! surprise!"). But not the green one: "egg." Then, the birds fly off ("good-bye/ good-bye/ good-bye/ egg"). At the turn of a page, the green egg now stands alone, larger than life, paired only with the word "waiting." The facing page splits into a 16-square grid with 16 green eggs inside... and 16 labels... "waiting." This is a lot of waiting.

Henkes says, "I was intrigued with the question, What happens when you use the same picture but change the word underneath it? And how does that change how you feel about the picture? As you look at the picture of the green egg paired with the word egg, and then at the picture of the green egg with the word waiting, there's a subtle difference in how the reader or listener interprets that image. And then if you take the image of the egg and draw it 16 times, it again changes the meaning."

One by one, the sweet little birds return to check on the progress of the unhatched green egg. They listen, eyes closed, for anything stirring inside, then they start to peck at the shell. One full page and four more quadrants show the birds pecking at the egg, eyes now shut tightly with the effort of it. Then there are 16 quadrants with nothing but "peck-peck-peck" written inside each square. (Says Henkes: "Where it says peck-peck-peck 16 times, I imagined a child poking the paper with his or her finger.") Then, "crack!" Then, "surprise!" The birds' eyes grow wide. It is a baby alligator! With the birds' distress registering only as a worried eyebrow, they fly off. In four more quadrants, the alligator is "alone, sad, lonely, miserable," in a gloomy (but also rather amusing) progression.

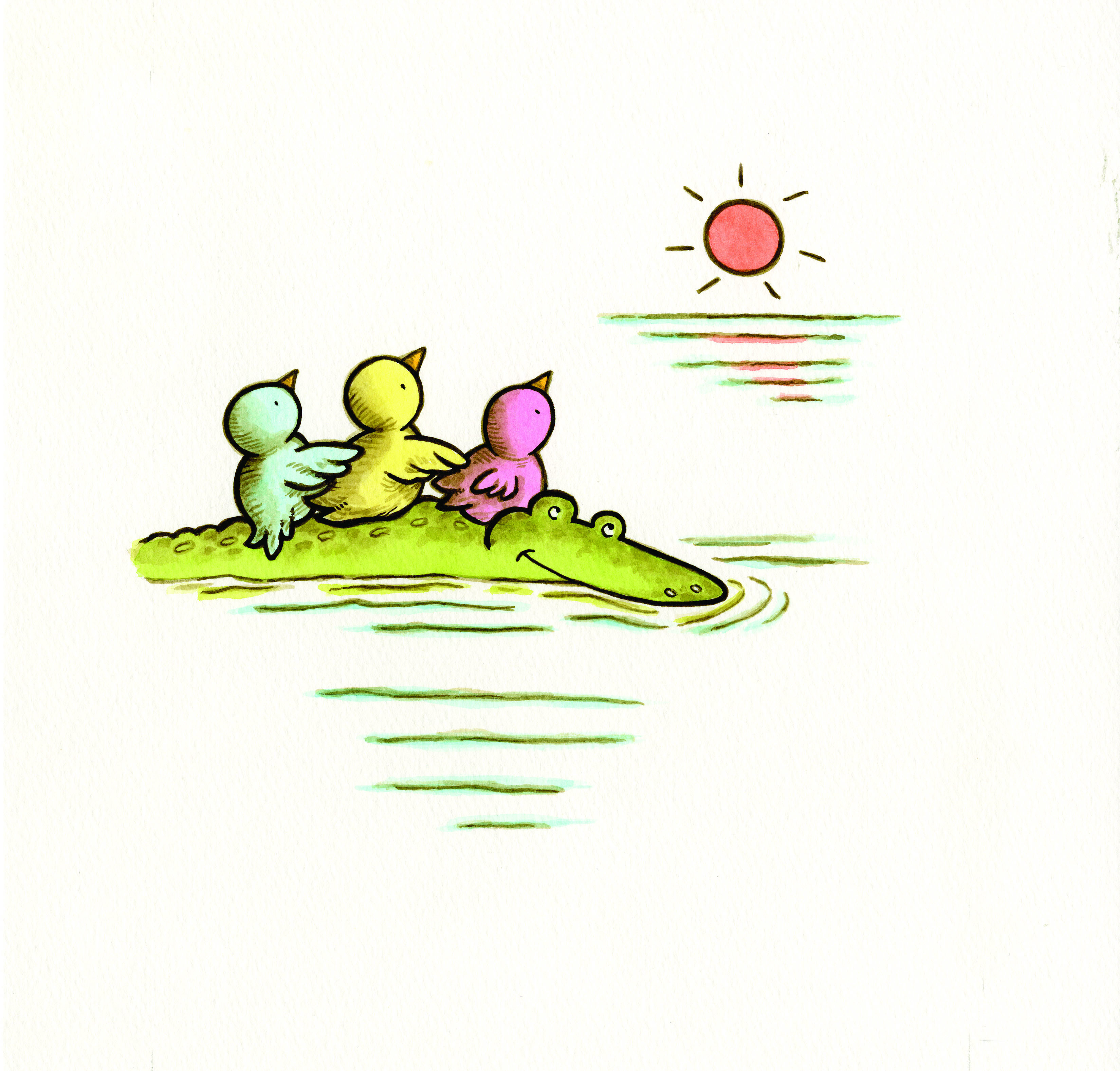

The birds return. They befriend the once-lonely alligator, sit on his bumpy, floating back and watch the orange sun set, but not before the sun turns into an orange egg. This surrealistic twist transforms the reading of Egg. Henkes eloquently explains this shift: "This is an altered reality where something big can come from something small, a world that's both real and unreal. Surreal in a gentle kind of way." "The end..." says the text beneath the big orange egg. But turn the page and it says "maybe," and an orange bird flies off the white page.

Every design detail in Egg is carefully considered. The lowercase title, "egg," is hand-lettered so that each letter is egg-shaped. The eagle-eyed will notice that each bird has different characteristics--for example, the pink bird likes to point at things. The final solid page is the same coral-orange color as the setting sun egg. The endpapers are a grid pattern, reflecting the four colors of the original eggs. ("It just came together in a moment where everything just seemed right, just BOOM," says Henkes.) Underneath the jacket, on the case, sits the word "egg" on a blue background, and five eggs in a row across the bottom.

So, what is Egg? Its story about being different may speak to children who feel like an alligator among birds. The story about how to handle waiting (do we just wait and wait patiently, or do we start pecking?) might be all too familiar to kids who want things to happen now. The story of how the birds fly away from the alligator in fear but return for friendship will be comforting to anyone who has felt alone. Egg is also a lesson in visual storytelling. How can an artist show the passage of time almost wordlessly? How do we "read" story panels? How does comic timing work? As ever, Henkes does a lot with a little, and in the breathing room he creates, children can let their imaginations soar. --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness