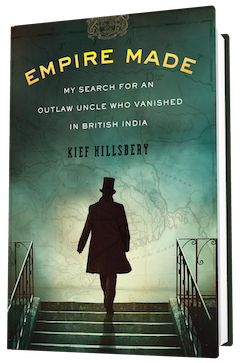

Empire Made: My Search for an Outlaw Uncle Who Vanished in British India

by Kief Hillsbery

Kief Hillsbery grew up with the legend of his great-grandfather's great-uncle Nigel, who had "gone out to India" and never returned to his family's home in Coventry, England. According to the many stories, he'd left the British East India Company abruptly and gone to live in Kathmandu; he'd been killed by a tiger; he'd been involved with shady dealings regarding a famous diamond. From childhood, Hillsbery always had "a clear sense that [the family] disapproved of Nigel and the vague notion that there was more to his story."

In Empire Made: My Search for an Outlaw Uncle Who Vanished in British India, Hillsbery describes his decades-long, on-and-off exploration into Nigel's life and death. It is an absorbing story, told with an eye for suspense and the odd, engrossing detail. Nigel's story does not lack for weird and glittery hints; it takes a deft hand to explore them with interest and not sensationalism, but Hillsbery is up to the task. His lovely descriptions bring to life a country that is worlds of difference from Nigel's English home. Sagar Island offers "houses like palaces, rising in their shining stucco masses from flowerbeds filled with imported English blooms on the undulating riverbank, their verandas spacious, their pillars lofty, their profiles Athenian." Hillsbery is astonished to find a rhododendron forest just where his family's stories placed one. "India," he writes, "is full of surprises."

Nigel set out for Calcutta in 1841 as a 20-year-old clerk for the East India Company. In 1975, Hillsbery was himself 20, headed for a college year abroad in Nepal, when his mother gifted him a sheaf of papers: all that remained of Uncle Nigel's letters home, most incomplete and in various stages of decay. She wanted her son to be the first in the family to track down Nigel's grave and pay his respects. The young man figured he would visit a cemetery or two and do his duty. But in fact he would embark upon years of research and travel through India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nepal.

Alternating chapters detail the author's own travels and Nigel's, the latter re-created using personal correspondence and official records from the 1840s. Necessarily, Empire Made also delves into British and Indian politics, and the nuanced racial and class-based prejudices and pressures that characterized the British East India Company for centuries. The background history that contextualizes this story can be convoluted, but Hillsbery wrestles this "historical quicksand" gamely, and his digressions enrich the sense of strange wonderment that characterizes this historical investigation. Readers will come away with a general sense of British-Indian relations, while focusing on the mystery of Nigel's fate.

Hillsbery's narrative neatly braids the threads of the two protagonists' parallel travels. Nigel Halleck's family background and education links into the narrator's interest in mountaineering, and in Nepalese culture and language. With a distant idea about the enigma of a lost great-uncle, the young Hillsbery takes one and then another detour from his own travels to investigate a cemetery, a shrine, a memorial. He listens to the tales told by locals "with Chaucerian relish" of past visitors, and he learns to check Nigel's letters as he travels, searching for references to each stop along his own way so that he can follow leads as they arise. This research on the move begins to yield new information, if only in hints.

Over the years and miles, Hillsbery uncovers a theory that Nigel was a deep-cover British secret agent; that he was connected to an important family, the Saddozais, by his close friendship with the Afghan prince Sa’adat ul-Mulk; that he was involved in some under-the-table dealings with the famous Koh-i-noor diamond. But beyond these dramatic stories, Hillsbery finds quieter details that link his own life story more closely to Nigel's than he could have ever expected.

Empire Made nears its end when Hillsbery visits a seeress. Stumped by Nigel's unexplained movements and his inexplicable retreat to a Hindu palace in Kathmandu, he submits to a friend's recommendation to supernatural assistance: "Her rates were reasonable, and I could always write about it." This woman's cryptic statements, and Hillsbery's later realizations about two pieces of information he'd uncovered, eventually help him to reach certain conclusions about Nigel's life. These conclusions are not supernatural, but worldly. In the end, this epic story of travel, research, family mystery and centuries-long colonial effort ends with uncertainty; but Hillsbery's voice in closing does find satisfaction in what he's learned. --Julia Jenkins

_Tobin_Yelland.jpg)