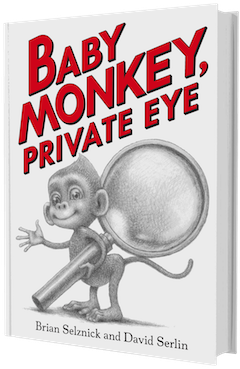

Baby Monkey, Private Eye

by Brian Selznick, David Serlin

"Who is Baby Monkey?" you might ask. A fantastic question. Really, it's quite simple. "He is a baby. He is a monkey. He has a job...." He is Baby Monkey, Private Eye.

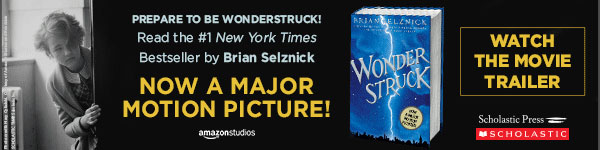

The concept of Brian Selznick and David Serlin's first literary collaboration is exactly what it sounds like: Baby Monkey is both a baby monkey and a detective, with an office straight out of film noir. The almost-200-page, early reader chapter book opens with "The Case of the Missing Jewels!" In Selznick's signature, highly detailed pencil illustration, Baby Monkey sits on his couch reading Famous Jewel Crimes, a book that is nearly the same size as he is. On the table next to him there are papers, a typewriter and more books; the lamp behind his head sits atop a file cabinet with one drawer ajar. On the corner of his large desk there is a classic black desk phone and a bust of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart; a coat rack near the door holds a trench coat and a fedora. The walls are decorated with heavily framed works of art including paintings of Maria Callas and Giuseppe Verdi and a poster from the 1935 Marx Brothers film A Night at the Opera. Through the frosted glass of his office door's window, a long-nailed hand can be seen reaching....

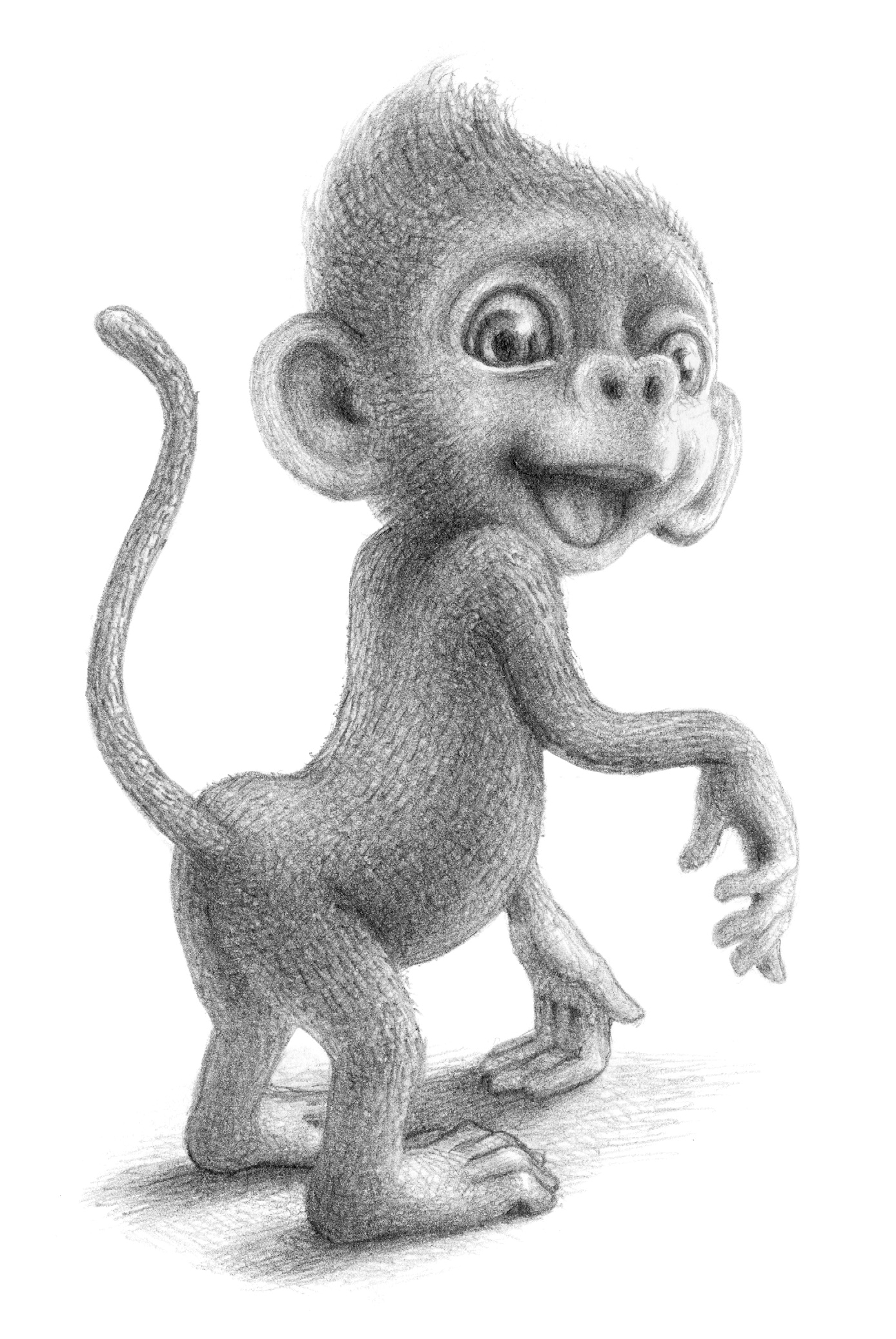

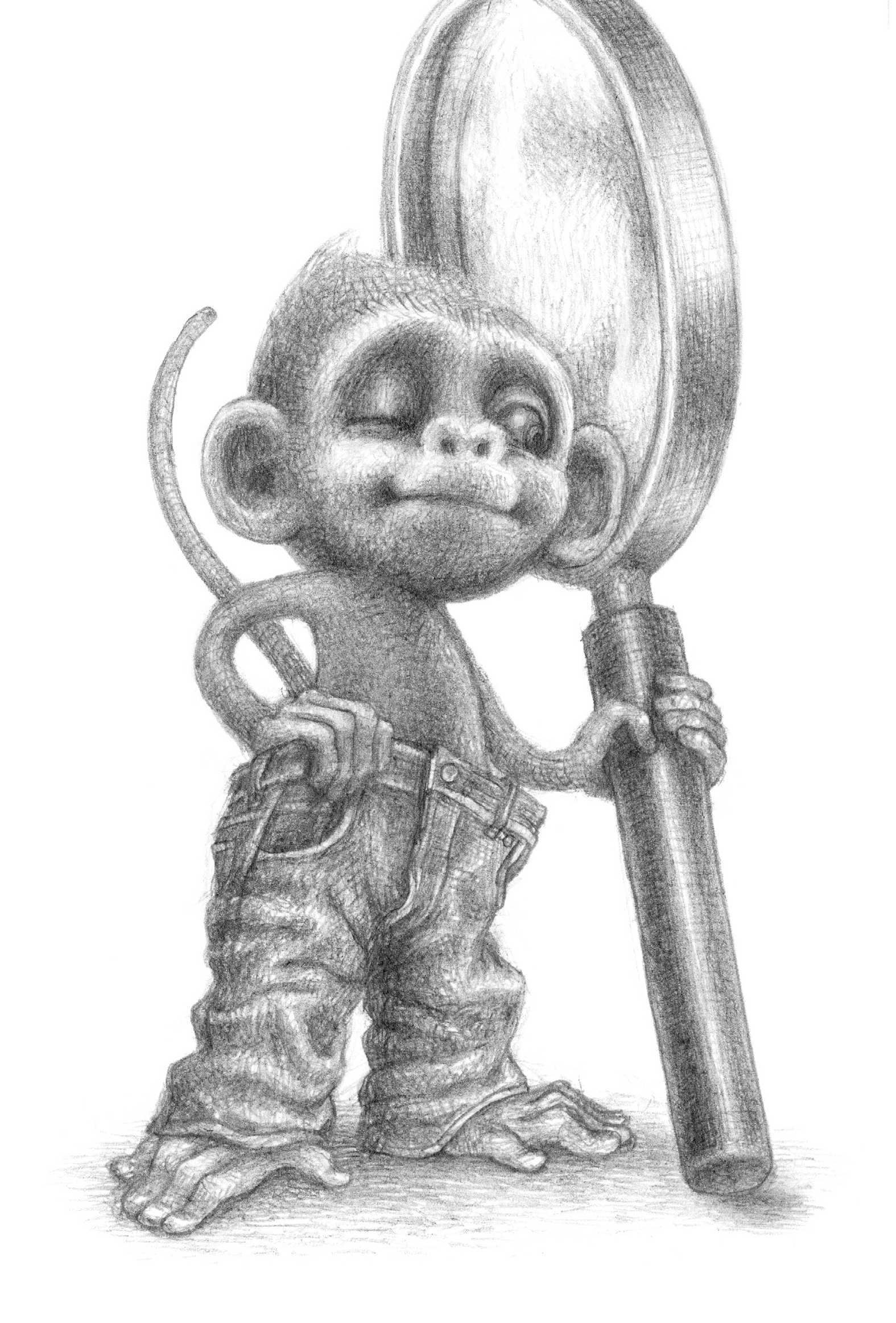

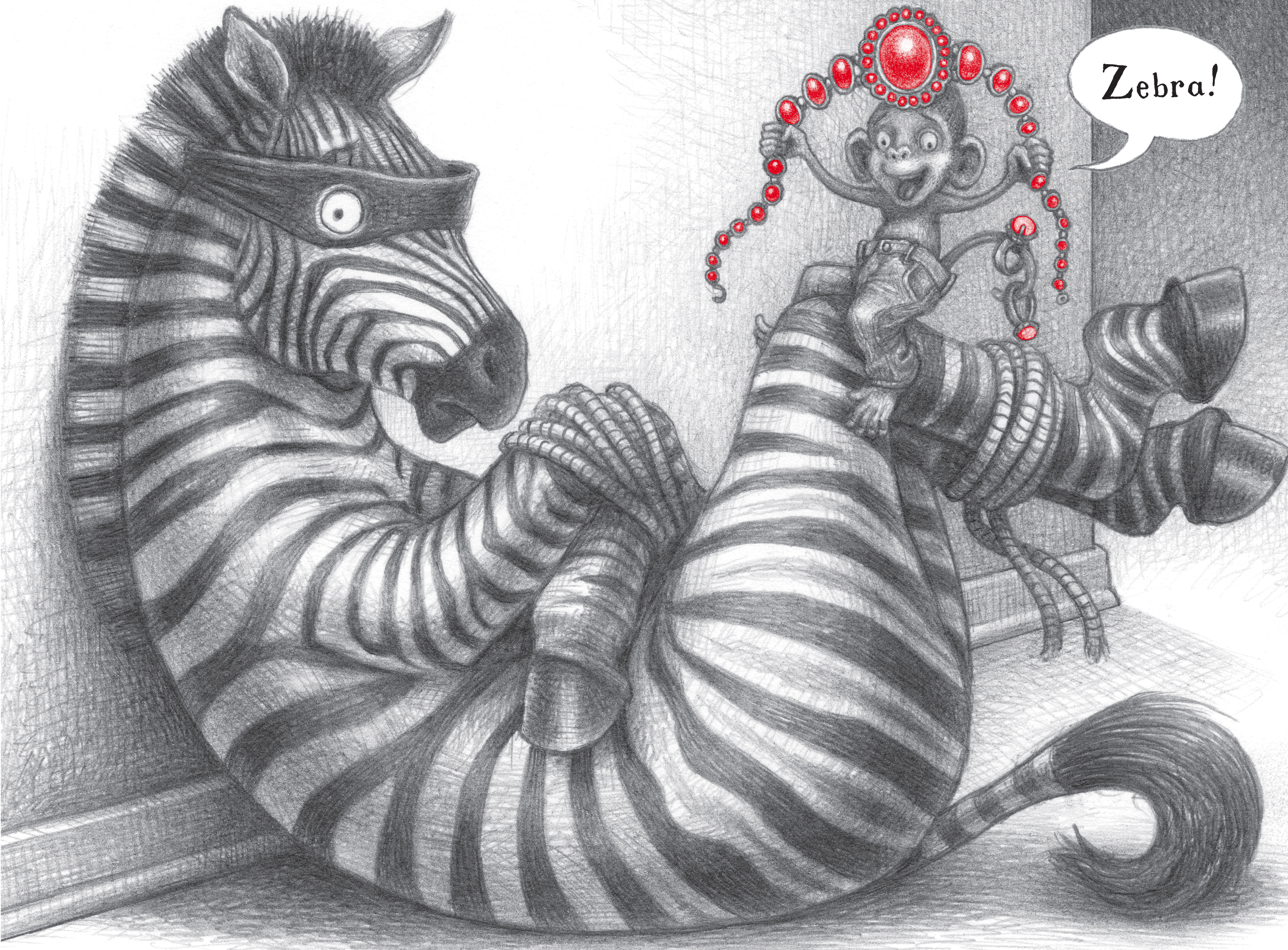

Through the door bursts a distraught woman (think Brünnhilde from Wagner's The Ring of the Nibelung). "Baby Monkey!" she exclaims, "Someone has stolen my jewels!" The opera singer has come to the right place--"Baby Monkey can help!" First, Baby Monkey uses his overly large magnifying glass to look for clues. Next, Baby Monkey sits behind his adult-person-sized desk and writes notes. Then it's time for a snack (baby carrots, prepared for Baby Monkey in a sandwich bag). Finally, Baby Monkey puts on his pants. Unfortunately, it can be quite difficult to put on pants when you're a baby monkey. After nine pages of trying (and failing) to get his hairy little body into jeans (with no hole for his tail, it is important to note), he succeeds: "Now Baby Monkey is ready!" By following a set of particularly distinct footprints, Baby Monkey solves the case: "Zebra!" "Hooray for Baby Monkey!"

This pattern of crime solving is repeated three more times in chapters two through four. With each new case, Baby Monkey's office décor changes to match the subject of the new chapter. In "The Case of the Missing Pizza!" Baby Monkey is sprawled on his couch reading Famous Pizza Crimes; a map of Italy takes Maria Callas's place; a poster for the 1969 Michael Caine film The Italian Job has replaced A Night at the Opera; the bust on the desk is now David, based on the sculpture by Michelangelo. As in the previous chapter, Baby Monkey looks for clues, takes notes, eats a snack, puts on his pants and then solves the case. Throughout the entire book, every illustration is black and white until the case is solved.Then the stolen item appears, colored in a bright, traffic-light red.

Selznick, whose 2007 highly illustrated middle grade work, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, won the Caldecott Medal and the Indies Choice Book Award for Children's Literature, once again pushes against the assumed format of children's books. Like other early reader chapter books, Serlin and Selznick's Baby Monkey, Private Eye follows some very specific rules: repetition is used, the font is large, the text and vocabulary are simple and there is copious art. But, where a work for early readers is usually somewhere in the range of 32 to 64 pages, Baby Monkey is 192 pages--three times the usual length. While it is, without a doubt, a book for younger readers, it looks (and feels) like a book "bigger kids" might be reading.

And what a book! As can be expected of any of Selznick's illustrated works, every page of Baby Monkey overflows with detail. All of the iterations of Baby Monkey's office are explained in a "Key to Baby Monkey's Office" at the end of the book where there is also a bibliography (those books Baby Monkey has been reading? All real books.) and an index that tells the reader every page where the item shows up as either text or picture.

The text is easily accessible to young readers, using elementary vocabulary that repeats in every chapter--by the third chapter, readers know by heart the order of Baby Monkey's activities and how he closes his cases. Selznick's illustrations add to the simple text, giving the work incredible depth and including treats for close (and older) readers to find. Baby Monkey is, of course, the star of the book and he is drawn in incredible detail: his face and postures are outstandingly expressive and engaging. Also, he's downright cute. It is near impossible to pick up Baby Monkey, Private Eye and not fall in love with the dedicated baby crime-solver. --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness

Brian Selznick is the Caldecott Medal-winning creator of the New York Times bestsellers The Invention of Hugo Cabret (adapted into Martin Scorsese's Oscar-winning Hugo),

Brian Selznick is the Caldecott Medal-winning creator of the New York Times bestsellers The Invention of Hugo Cabret (adapted into Martin Scorsese's Oscar-winning Hugo),  Did you know from the start that you wanted to create an early reader?

Did you know from the start that you wanted to create an early reader?  How did the "Baby Monkey puts on his pants" visual joke develop?

How did the "Baby Monkey puts on his pants" visual joke develop? How did you find this balance between illustration and text? And how did you decide upon this color palette?

How did you find this balance between illustration and text? And how did you decide upon this color palette?