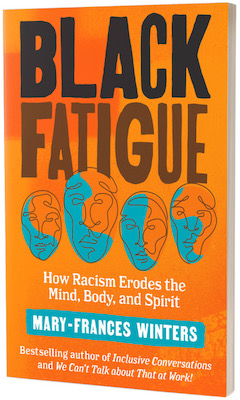

Black Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and Spirit

by Mary-Frances Winters

In 1964, notable Black civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer said: "I am sick and tired of being sick and tired." More than half a century later, Mary-Frances Winters provides an expansive, galvanizing exploration of this still-present state in Black Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and Spirit.

Winters (Inclusive Conversations; We Can't Talk About That at Work!; Only Wet Babies Like Change) has devoted her life to communicating about social justice. As a teenager in the late 1960s, she was editor of her school newspaper and wrote about contemporary civil rights leaders, women's rights and the Vietnam War--yet saw her pieces censored by teachers who saw them as "too controversial." In college, she again edited the school paper, but found herself contending with professors and students who assumed she was at the university not as a regular admission but one from the Equal Opportunity Program.

After facing continued racism and sexism in the workplace, Winters founded a consulting firm to provide companies training on diversity, equity and inclusion. Over the three-plus decades since, she noticed a common sentiment from Black workers: exhaustion and frustration, not just from experiencing racism, but from trying to communicate what they faced to white employees who were disbelieving. They were, she realized, experiencing Black Fatigue.

Winters explores these experiences of her own and others in Black Fatigue, defining the concept as "repeated variations of stress that results in extreme exhaustion and causes mental, physical and spiritual maladies that are passed down from generation to generation." She delves into its history and complexity, sharing research on ways it manifests variously in men, women and members of the LGBTQ+ community, and offering suggestions for combatting Black Fatigue and racism itself.

Winters sees compelling ties between current events and significant events in the past, drawing connections between the fates of Emmett Till and the more recent deaths of Trayvon Martin, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor--noting the painful core at the heart of these stories: willful, blatant disregard for Black lives and the circumstances under which they continue to be cut short. In addition to examining outright violence, Winters looks at ways racism affects Black Americans' general health. She includes the historical mistreatment of Black people in the American health-care system, as well as data on the Covid-19 pandemic's disproportionate effects on Black Americans.

With clear examples and concise analysis, Winters emphasizes how much language matters. She recommends reframing: instead of saying "Black people are exhausted," say, "Racism is exhausting." Likewise, instead of "Black people can't get loans," try "Banks disproportionately deny Black people loans." And, critically, not "Black men are 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police," but "Police are 2.5 times more likely to kill Black men than white men." She also draws from the language of trauma-informed care, which "reframes the thinking of the caregiver from 'What is wrong with this person?' to 'What has happened to this person?' "

Throughout Black Fatigue, Winters uses the phrase "Then is now" to highlight a lack of progress and the cyclical nature of racism and its effects on Black Americans, culling from data on wealth disparity, unequal access to secure jobs and housing and other various roadblocks in avenues toward building equity. Drawing on even more current news--and echoing her own college experience--she also notes the perpetual discrimination current Black students face. "In 2018," Winters recalls, "a white student called the police to report that a Black female was sleeping in a common area of a dorm at Yale University. The white student was concerned that she did not belong there, and it made her uncomfortable." Yet again: Then is now.

Candid and conversational, Winters directly addresses her audience and their various motivations. She is explicit about her goals and hopes for her readers: "I ask white people to read this book not only to be educated on the history of racism but to also be motivated to become an anti-racist, an ally and a power broker for systemic change. For Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) who read this book, I hope that it will also be educational and affirming and when one of your white colleagues asks you to educate them, you can refer them to this resource, so as not to exacerbate your fatigue."

When the specter of racism seems to be everywhere, and when stories in the news make it feel insurmountable, her suggestions for action are both inspiring and practical. Fans of Robin DiAngelo, Ijeoma Oluo and Ibram X. Kendi will find much to appreciate in Winters's work--as will anyone wanting to better understand how racism permeates culture and ways people both wittingly and unwittingly perpetuate it. Readers will finish Black Fatigue invigorated, ready to evolve from "Then is now" to instead creating a better now--and Winters provides the tools for us to start... now. --Katie Weed