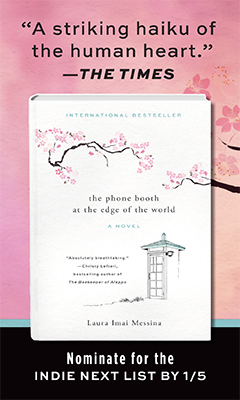

The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World

by Laura Imai Messina

Since Yui lost her mother and her daughter in the 2011 tsunami that devastated Japan, she has been paralyzed by grief, simply going through the motions of life. But then, via the radio show she hosts, Yui hears about a phone booth in a garden by the sea, which holds a disconnected phone: a peaceful place for people to come and talk to their lost loved ones. Italian novelist Laura Imai Messina (Tokyo Orrizontale), a long-time resident of Japan, weaves Yui's moving story together with those of other visitors to the "wind phone" in The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World, her third novel (and the first translated into English)

Thoughtful and tender, full of small daily moments and acts of kindness, Messina's novel is a testament to the power of community (and a bit of whimsy) in moving forward after loss.

Messina's wind phone is based on a real-life phone booth in Bell Gardia, a garden built in 2010 on the outskirts of Otsuchi, Japan. Like Itaru Sasaki, the real-life custodian of the phone booth, the owners of the garden in the novel (an elderly couple known simply as Suzuki-san and his wife) open their property to visitors as a place of healing. On her first visit there, Yui meets Takeshi, a man who has recently lost his wife. His young daughter, Hana, has been mute since her mother's death. During their subsequent trips (which they begin making together), Yui and Takeshi meet others who are grieving and making their own pilgrimages to the phone booth; gradually, they form a kind of community. When another severe storm threatens the existence of the wind phone, Yui takes matters into her own hands.

The book's main narrative thread follows Yui and Takeshi after they meet, but Messina also takes readers back in time to the first frantic, displaced days after the tsunami, when Yui slept in a school-turned-shelter for weeks while searching for her mother and her daughter. Messina's portrayal of the storm and its aftermath is matter of fact and unstinting; she lays out the broad outlines of the tragedy without trying to explain or make sense of it. As Yui begins to recover, she focuses on small details, like the blue plastic picture frame carried everywhere by a man with vacant eyes.

Messina intersperses her spare, lyrical narrative with tiny chapters formed mostly of lists: the contents of Hana's lunchbox, the playlist of songs on a particular evening at the radio station, the clothes Yui's mother and daughter were wearing on the morning they disappeared. These lists of quotidian details offer flashes of normalcy (and sometimes humor) amid the larger narrative of life-altering grief with which the characters are grappling. Some of the details--a paper book cover, an extract from a radio show--seem to have no immediate relevance, while some (like the statistics of tsunami victims, or the dictionary definition Takeshi finds for "family") are quite apt.

Although Yui becomes a faithful visitor to Bell Gardia, for months she cannot bring herself to go inside the booth. She drives down with Takeshi (always eating chocolate to stave off nausea at the first sight of the sea), and converses with Suzuki-san and the other visitors to the wind phone. But she sits in the garden rather than enter the phone booth; she's not sure what she would say to her mother or her daughter, given the chance. Meanwhile, back in Tokyo, she and Takeshi tentatively begin to merge their lives. Yui gets to know his daughter and his mother, and begins spending evenings at their home, even changing her work schedule at the radio station. Both she and Takeshi struggle to make their peace with the loss of those they have loved, but they help one another to move forward, one day at a time.

Though Messina's narrative is mainly focused on Yui and Takeshi, she draws thoughtful, nuanced portraits of several secondary characters--gentle, wise Suzuki-san, who maintains Bell Gardia; Shio, a teenager and aspiring medical student who visits the garden to talk to his father; Takeshi's mother, who must adjust to Yui's sudden presence in her family's life. The narrative gives glimpses into these characters' inner lives and the sometimes surprising effects their actions have on one another. All of them are, in some way, dealing with unimaginable loss, and their quiet presence in each other's lives helps them to keep going and even work toward a hopeful future.

The wind phone is perhaps an unusual response to grief, but both in the novel and in real life, it provides a place for grieving people to have necessary conversations, to acknowledge their sadness and other complicated emotions, and--perhaps--to let their grief lift and float out over the sea. --Katie Noah Gibson