The Black Friend: On Being a Better White Person

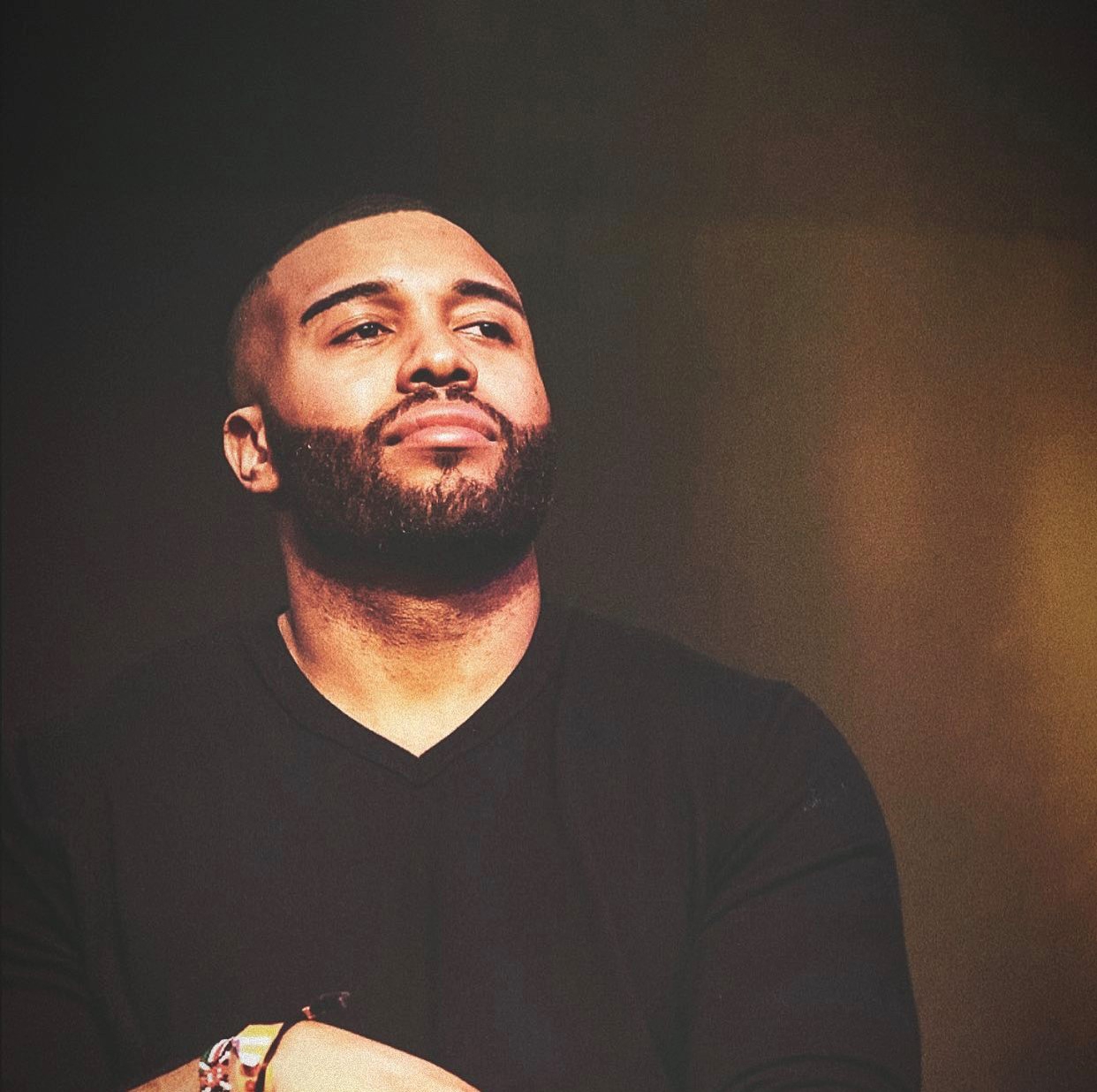

by Frederick Joseph

The Black Friend is a handbook for teen readers ready to commit to becoming antiracists. It's also an incredibly rich, moving and entertaining read.

In an exceptionally approachable style--he does want to be his readers' Black Friend, after all--award-winning marketing professional, activist and philanthropist Frederick Joseph addresses the systemic racism and white supremacy that have devastated the lives of people of color for hundreds of years. He does this hoping that white people will take the racial justice baton from people of color and thus take on the work of dismantling these systems. As he writes, "the oppression that white people have inflicted on people of color since, well, damn, the very inception of this country can only be undone by the oppressors (white people)."

Speaking directly to his intended readers--particularly white people "who want to do better, who want to be better"--Joseph asks for accountability for the "historic and current inequities and disparities plaguing Black people and people of color as a whole." He also aims to provide validation for people of color, reminding them that they are not alone in their experiences in the world. Ranging in tone from warm to passionate, Joseph asks white readers to accept him as their Black friend: someone who, in the spirit of friendship and positive change, will speak the truth and call them out for hurtful or inappropriate words and behaviors.

Joseph shares anecdotes, introduces important Black cultural and historic figures, describes racist systems and offers suggestions for becoming a better white person. He makes frequent (and often humorous) use of shaded sidebars with explanations and elaborations on his topics. For example, in the chapter called "This Isn't a Fad; This Is My Culture," he inserts a sidebar explaining the difference between cultural appropriation and appreciation, with questions to ask oneself. "Is the thing I want to wear used in specific ceremonies or rituals? If so, say no." Page by page, Joseph works to break down cultural stereotypes and missteps. He believes that the white assumption that people of color aren't "dynamic or layered"--that they wouldn't be able to enjoy Star Wars or Ed Sheeran, for example--comes from the fact that many white people have not had to step out of their own "cultural comfort zone": the mainstream. Since, as he writes, so much of mainstream culture is rooted in whiteness, people of color "grow up learning, knowing, and even loving many things that aren't rooted in [their] culture."

Joseph incorporates frequent, fun and relevant cultural references to television, YouTube, sports teams, music and video games. Also included are interviews with contemporary artists, musicians, writers and activists such as The Hate U Give author Angie Thomas; actor and playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney (In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue); activist and social impact consultant Jamira Burley; storyteller, author, rapper, spoken-word artist and TED Talk speaker Joel Leon; and racial justice activist and entrepreneur Saira Rao. These contributors offer visionary perspectives and opinions on racism in various industries.

Throughout the book, Joseph includes stories about his own experiences of racism. His high school had many more white people than his middle school. His white friends and their families regularly reflected casual racist stereotypes about him, asking what "hood" he lived in, joking about his mother making fried chicken and assuming he could dunk a basketball and aspired to the NBA. Strangers who were amazed at his "articulate" way of speaking suggested that he consider college, even though he was already an honors student fully intending to attend college. Painful examples like these fill the pages, but Joseph does not spare himself and his own part in these encounters, acknowledging the ways he played into the faulty assumptions people made. He describes how, in trying so hard to fit in, he would laugh and go along with the offensive comments, squashing his frustration and discomfort by allowing himself to be the token Black friend (as opposed to an actual Black friend, as he clarifies in the introduction). This way of acting may have made him popular in high school, but it was not sustainable, nor was he being true to himself. As he grew older, he began to seek new ways of navigating the inherent racism in his communities.

Packed with hefty ideas and information from start to finish, The Black Friend concludes with what Joseph drily calls "your very own Encyclopedia of Racism," as well as short bios of "People and Things to Know" and a fabulously rich and diverse playlist (he comments throughout the book about how surprised white people are to find that he likes a wide range of music, including soft rock).

White readers who want to do and be better may find that The Black Friend provides the tools they need for crossing over from being someone who empathizes with the struggles of Black people to someone who is an active, vocal and effective antiracist. And, in the best of all worlds, a good white friend. --Emilie Coulter