However Long the Night: Molly Melching's Journey to Help Millions of African Women and Girls Triumph

by Aimee Molloy

In her first full-length solo venture, Aimee Molloy (Then They Came for Me: A Family's Story of Love, Captivity, and Survival, written with Maziar Bahari) brings readers a beautifully rendered portrait of Senegal and its generous people, and of Molly Melching, the American who fell in love with both and dedicated herself to bringing them education on their own terms. Molloy's account of a modern-day heroine glows, and with precise, succinct strokes, she draws the reader into Senegalese lives.

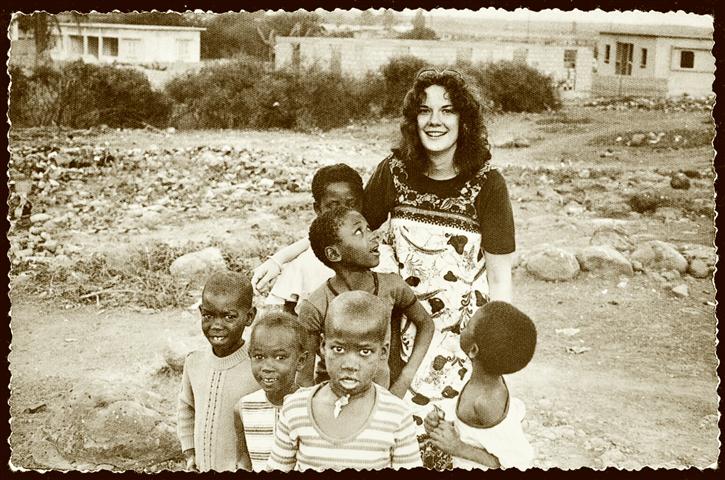

Melching came to Africa first as a wide-eyed college exchange student from Illinois. From the moment she arrived, Senegal became her second home, and Melching eagerly embraced the culture and language, falling particularly in love with the villages outside the French-influenced city of Dakar. Instead of racing back to America and modern conveniences like electricity and air conditioning after her term ended, Melching chose to remain in Senegal. Noticing that schools were teaching in French when children spoke the local language, Wolof, at home, Melching began to question traditional European methods of bringing education to the Senegalese. In time, her respect for the people and society led Melching to develop educational programs that considered what the Senegalese themselves wished to learn and imparted information in their native tongue. These empowering strategies were radical at the time, but within a decade Melching had piloted a fast-growing program called Tostan ("breakthrough" in Wolof) that brought villagers education, encouraged development projects and enhanced rather than hindered villages' communal self-esteem.

What Melching didn't anticipate, what no one could have anticipated, was that Tostan held the key to empowering Senegal's women and ending the acceptance of a key piece of Senegalese culture: female genital cutting (FGC). When Molly Melching arrived in Senegal in 1974, women had suffered cutting for generations. Believing (incorrectly) that their Islamic faith required compliance with "the tradition," mothers subjected their daughters to the painful and sometimes life-threatening procedure not out of cruelty, but love. An uncut woman would never find acceptance within the community or make a good marriage, and no mother would set her daughter up for shunning.

Perhaps most impressive is Molloy's ability to translate the philosophy of a cultural mindset so different from our own. Rather than paint the practitioners of FGC as villains and Melching as the Great White Hope who rescues the next generation of girls, Molloy makes certain to portray her realistically, as a facilitator of education. It is the female Tostan students themselves, armed with new knowledge about their bodies, human rights, and religion, who refuse to allow their daughters to suffer as they have suffered with FGC and the fear that admission of pain or doubt will bring scorn and dishonor. At the same time, these women as a group are a force of nature with the ability to change the fate of their nation's girls or close their eyes and continue to embrace a tradition that, while dangerous, carries the sanctity of generations of routine. This is their biography as much as it is Melching's, and the efforts of the first village to stop FGC attract unlikely allies. From a woman who quit her role as a traditional cutter and became an anti-FGC advocate to a respected elderly man who walks from village to village in the scorching heat to spread information about the dangers of FGC to a host of mothers and grandmothers, the Senegalese women, and some supportive male counterparts, show a compassion and concern for each other that transforms a country into a family. Rather than diminish Melching's importance, Molloy's holistic approach to her subject matter shows Melching as the pebble that began the ripples. The women of Senegal bring about the change, but without Melching and Tostan, they would not have known change was needed. In fact, the word tostan is a metaphor for this effect. Cheikh Anta Diop, a Senegalese professor and politician, told a young Melching, "Literally, the word means the hatching of an egg.... That chick becomes a hen and lays eggs... and so there are more chicks that become hens and the process continues for generations. For me, the word signifies the idea that as people gain new knowledge in a nurturing and environment they can then reach out and share it with others, who in turn do the same."

From the spirit of one woman to the might of many, Molloy delivers an inspiring narrative that proves the world can be changed through the bravery of individuals and the love of communities. --Jaclyn Fulwood

_Tostan.031913.JPG)